What Makes a Good Tester?

Essential skills and mindset traits

I once worked with a tester who had every certification imaginable. ISTQB Foundation. ISTQB Advanced. Certified Agile Tester. A wall full of credentials that said she knew testing inside and out.

She was mediocre at best.

I also worked with a former barista who stumbled into QA because the company needed bodies. No certifications. No formal training. Just a knack for noticing when things felt off.

She was exceptional.

This isn’t an argument against education or credentials. It’s an observation about what actually makes someone good at testing. The skills and mindsets that separate great testers from adequate ones aren’t always the things you’d put on a resume.

Today we’re exploring what truly makes a good tester — the essential skills you can develop and the mindset traits that might already be part of who you are. Some of this can be learned. Some of it is about recognizing and nurturing tendencies you already have.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Testing Talent

Here’s something that might be controversial: not everyone is cut out for testing.

That’s not elitism. It’s honesty. Just like not everyone is cut out to be a surgeon, a trial lawyer, or a stand-up comedian. Different roles require different combinations of skills and temperament.

Some developers make terrible testers — not because they lack intelligence but because they can’t shift from “making it work” mode to “trying to break it” mode. Some detail-oriented people struggle because testing also requires big-picture thinking. Some creative people flounder because testing requires discipline and systematic approaches alongside creativity.

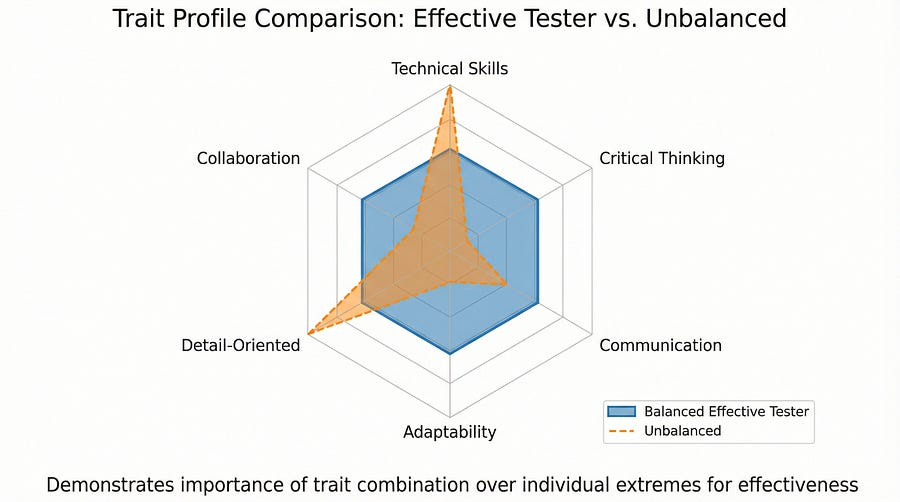

Good testing requires a specific combination of attributes that don’t always travel together. Analytical thinking and creativity. Patience and urgency. Skepticism and collaboration. Attention to detail and ability to see the forest, not just the trees.

The good news: most of these attributes can be developed. Understanding what makes a good tester helps you identify which skills to strengthen and which natural tendencies to lean into.

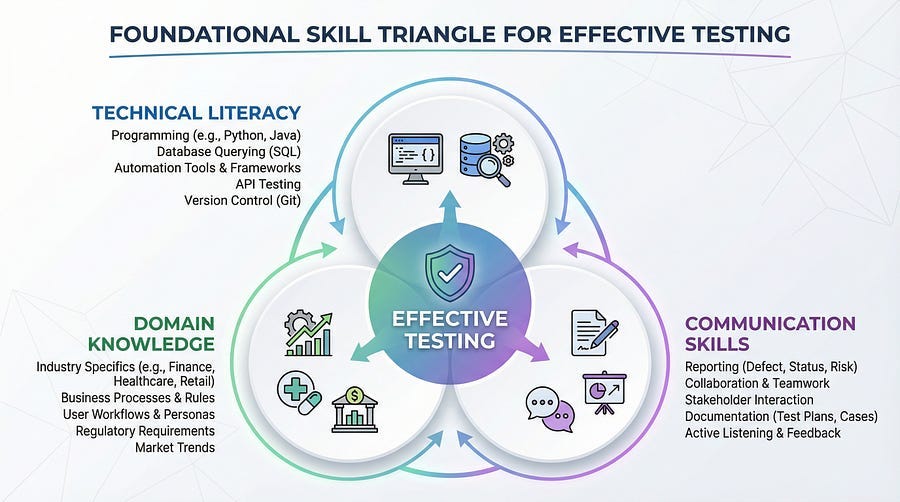

The Core Skills

Let’s start with the learnable stuff — skills you can develop through practice and study.

Technical Literacy

You don’t need to be a developer. But you need to understand enough about how software works to test it effectively.

This means understanding concepts like databases, APIs, client-server architecture, and basic programming logic. Not mastery — literacy. You need to read and understand, not write and architect.

When a developer says “the bug might be in the caching layer,” you need to understand what that means. When you’re testing an API, you need to understand what a request and response are. When something fails, you need to have enough technical intuition to provide useful information about what might have gone wrong.

Technical literacy also helps you communicate. Developers respect testers who can speak their language. Bug reports that say “the thing doesn’t work” get deprioritized. Bug reports that say “the POST request to /api/users returns a 500 error when the email field contains unicode characters” get fixed.

How to develop it: Build something simple. A basic web application, a small automation script, anything that forces you to understand how code becomes software. Read documentation for systems you test. Ask developers to explain architecture decisions. Take online courses in programming fundamentals — not to become a programmer but to understand how programmers think.

Domain Knowledge

The best testers understand not just the software but the world that software operates in.

Testing a healthcare application? You need to understand patient workflows, regulatory requirements, and what happens when medical software fails. Testing financial software? You need to understand transactions, compliance, and the consequences of calculation errors. Testing an e-commerce platform? You need to understand customer journeys, payment processing, and inventory management.

Domain knowledge helps you test what matters. Without it, you might thoroughly test a feature that’s technically correct but completely wrong for how users actually work. With it, you immediately recognize when something doesn’t make sense for the business context.

How to develop it: Become a student of your domain. Read industry publications. Talk to users. Understand the business problems the software solves. Ask “why” constantly — why does this feature exist? Why do users need it? Why does the workflow go this way?

Communication Skills

Testing creates information. Communication turns that information into action.

You need to write bug reports that are clear, complete, and actionable. You need to explain test results to stakeholders who don’t understand testing. You need to advocate for quality without being dismissed as negative or obstructionist. You need to have difficult conversations when you find serious problems.

Good testers are often the bearers of bad news. The skill is delivering that news in ways that lead to fixes rather than defensiveness.

How to develop it: Practice writing bug reports that someone else could reproduce without asking follow-up questions. Learn to present test results in terms of business impact, not just technical details. Study how to give constructive feedback. Pay attention to which of your communications lead to action and which get ignored — figure out what makes the difference.

Analytical Thinking

Testing generates enormous amounts of information. Analytical thinking is how you turn that information into insight.

This means identifying patterns across multiple test results. It means recognizing when a specific bug is actually a symptom of a broader problem. It means understanding risk and prioritizing testing effort toward what matters most. It means not just finding problems but understanding why they exist.

Analytical testers don’t just report “button doesn’t work.” They investigate, find that the button fails on forms with more than five fields, recognize the pattern, and identify that the underlying issue is a JavaScript timeout that affects multiple features.

How to develop it: When you find a bug, don’t stop there. Ask why it exists. Look for related bugs. Try to understand the root cause, not just the symptom. Practice categorizing and grouping test results to identify patterns. Learn basic statistical thinking to recognize when results are significant versus random noise.

Test Design

Testing without strategy is just clicking around hoping to stumble on bugs. Test design is the skill of systematically identifying what to test and how.

This includes understanding techniques like equivalence partitioning, boundary value analysis, decision tables, and state transition testing. These aren’t just academic concepts — they’re practical tools for ensuring you test thoroughly without testing everything (which is impossible).

Good test design also means knowing when to apply which techniques. Exhaustive combinatorial testing makes sense for a payment calculator with a few inputs. It’s pointless for a free-form text field with infinite possibilities. The skill is matching technique to situation.

How to develop it: Study formal test design techniques. Then apply them consciously until they become intuitive. For every feature you test, explicitly identify your test design approach before you start. Review your test designs afterward — did you miss important scenarios? Would a different approach have been more effective?

Tool Proficiency

Modern testing involves tools. Test management systems. Bug tracking software. Automation frameworks. API testing tools. Performance testing tools. Monitoring dashboards.

You don’t need to master every tool, but you need enough proficiency with the tools your team uses that they help rather than hinder your work. You also need enough awareness of what tools exist that you can recommend appropriate ones when needs arise.

Tool proficiency isn’t about the tools themselves — it’s about leverage. The right tool used well multiplies your effectiveness. The wrong tool or poor tool usage wastes time.

How to develop it: Get competent with the tools your organization uses. Explore tools for gaps in your current toolkit. Learn at least one automation framework well enough to create basic automated tests. Stay aware of new tools and approaches without chasing every shiny new thing.

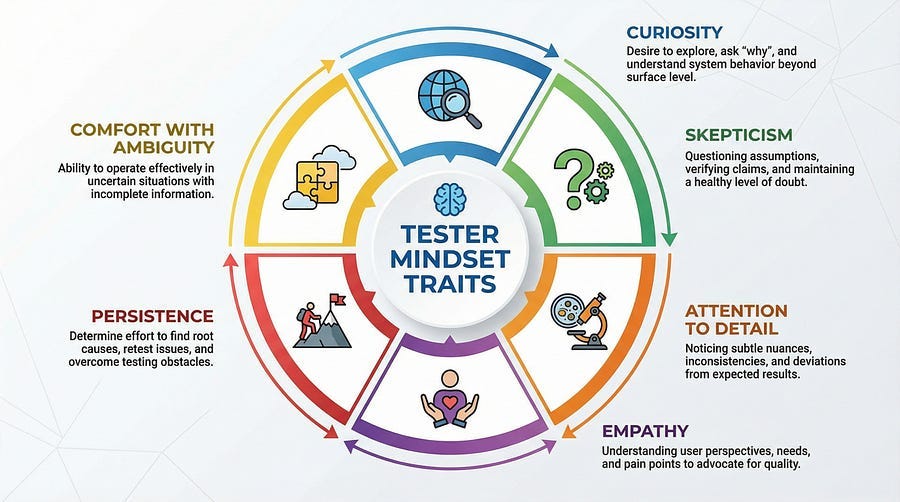

The Mindset Traits

Skills can be learned, but mindset is different. These are ways of thinking and approaching the world that make testing feel natural. Some people have these traits instinctively. Others develop them through deliberate practice. Either way, they’re essential.

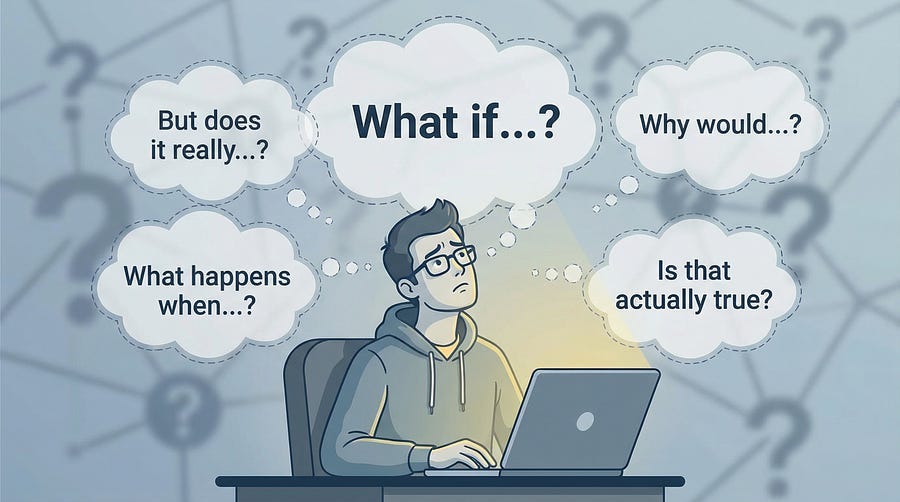

Curiosity

Good testers want to know how things work. Not because they need to — because they can’t help it.

Curiosity drives exploration. A curious tester doesn’t stop at “this feature does X.” They want to know what happens if they do Y instead. What’s behind that error message? Why does the system behave differently on Tuesday than Monday? What happens if you do something the designers never anticipated?

Curiosity also drives learning. Curious testers constantly absorb new knowledge about systems, domains, tools, and techniques. They ask questions others don’t think to ask.

The opposite of curiosity is assumption. Testers who assume they know how something works miss the bugs that live in the gaps between assumption and reality.

Cultivating curiosity: Practice asking “why?” and “what if?” relentlessly. When something works, ask why it works. When something fails, ask what else might fail in similar ways. Treat every system as a puzzle to be understood, not just a checklist to be verified.

Skepticism

Good testers don’t believe the documentation. They don’t believe the developers. They don’t believe the users. They don’t believe themselves.

This isn’t cynicism or distrust. It’s the recognition that what people say and what’s actually true are often different things. The spec says the feature does X. Does it? The developer says the bug is fixed. Is it? The user says they need Y. Do they really?

Skeptical testers verify. They question assumptions. They look for evidence. They treat every claim as a hypothesis to be tested rather than a fact to be accepted.

This skepticism extends to their own work. Good testers question whether their tests are actually testing what they think they’re testing. They wonder whether they missed something. They don’t assume they found all the bugs just because they didn’t find more bugs.

Cultivating skepticism: Practice doubting. When someone tells you something, mentally append “…but is that actually true?” Look for evidence that contradicts claims, not just evidence that supports them. Review your own work with the assumption that you made mistakes somewhere.

Attention to Detail

Bugs hide in details. Off-by-one errors. Missing null checks. Subtle inconsistencies between screens. The wrong date format. A misspelled word that breaks functionality.

Good testers notice things that others miss. They spot the one pixel that’s wrong, the response that took 200 milliseconds longer than expected, the edge case that almost nobody would encounter.

But attention to detail isn’t just about noticing small things. It’s about recognizing which small things matter. A typo in a marketing headline might be embarrassing. A typo in a medication dosage might be deadly. Good testers apply their attention proportionally to importance.

Cultivating attention to detail: Slow down. Rushing is the enemy of noticing. Practice observation exercises — describe a familiar object in detail, then look at it and see what you missed. Review your work after you think you’re finished. Create checklists for things you tend to overlook.

Empathy

Software is used by humans. Good testers think like those humans.

Empathy means understanding how users actually think and work, not how designers assumed they would think and work. It means recognizing that users make mistakes, get confused, have bad days, and use software in contexts designers never imagined.

An empathetic tester thinks: “What if someone is using this on their phone while walking? What if they’re elderly and don’t see small text well? What if they’re stressed and not reading carefully? What if they’ve never seen software like this before?”

Empathy also applies to colleagues. Understanding why developers make certain decisions helps you communicate more effectively. Understanding why stakeholders have certain priorities helps you frame test results in terms they care about.

Cultivating empathy: Talk to actual users. Watch them use the software. Ask about their context, their frustrations, their goals. Put yourself in the mindset of different user types when testing. Consider accessibility not as a checklist but as a way of ensuring everyone can use the software.

Persistence

Some bugs don’t want to be found. They hide behind specific sequences of actions, particular data combinations, or intermittent conditions. Finding them requires persistence — the willingness to keep investigating when you sense something is wrong even though you can’t prove it yet.

Persistence also matters when facing resistance. When developers insist a bug isn’t real. When stakeholders pressure you to approve a release you have concerns about. When you’ve run the same test a hundred times and it keeps passing but something still feels off.

The opposite of persistence is giving up too easily. Accepting “works on my machine” as an answer. Closing a bug because you couldn’t reproduce it once. Approving a release because you’re tired of fighting.

Cultivating persistence: Set a rule: when you suspect something is wrong, investigate until you either find it or can articulate exactly why you’re confident it’s not there. Practice distinguishing between persistence (continuing to investigate something worthwhile) and stubbornness (refusing to accept you’re wrong). Build stamina for frustrating problems.

Comfort with Ambiguity

Real testing rarely involves clear specifications, complete requirements, and unambiguous expectations. Good testers function effectively even when they don’t have all the information they want.

This means making reasonable assumptions and documenting them. It means testing based on user needs when specifications are unclear. It means providing qualified assessments rather than refusing to test until everything is perfect.

Comfort with ambiguity doesn’t mean accepting chaos. Good testers push for clarity where it matters while adapting to uncertainty where it’s unavoidable. They know when ambiguity is acceptable and when it must be resolved before testing can be meaningful.

Cultivating comfort with ambiguity: Practice identifying what you actually need to know versus what would be nice to know. Make decisions with incomplete information and observe the results. Distinguish between ambiguity that should be resolved (and advocate for resolving it) versus ambiguity you can work around.

The Meta-Skill: Switching Perspectives

If there’s one skill that underpins all the others, it’s the ability to switch perspectives. Good testers constantly shift how they’re looking at the software.

User perspective: How will real people actually use this? What mistakes will they make? What will confuse them?

Developer perspective: How is this likely implemented? Where might bugs hide given the technical approach?

Business perspective: What are the stakes if this fails? What’s the actual risk to the organization?

Attacker perspective: How could someone abuse this feature? Where are the security vulnerabilities?

Support perspective: What questions will customers ask? What edge cases will generate tickets?

Operations perspective: How will this perform at scale? What happens when it fails?

Switching perspectives isn’t about becoming an expert in all these areas. It’s about briefly adopting different viewpoints to see things you’d miss from your default perspective.

A tester who only sees software from one angle misses bugs that are obvious from another angle. The ability to rapidly switch perspectives is what enables comprehensive testing without requiring comprehensive expertise.

What Good Testers Don’t Need

Let’s dispel some myths about what testing requires.

You don’t need to be a developer. Technical literacy helps, but you don’t need to write production code. Some of the best testers have minimal programming skills.

You don’t need to be pessimistic. Skepticism and pessimism are different. Skeptical testers question assumptions. Pessimistic testers assume everything will fail. The former is useful; the latter is exhausting.

You don’t need to be confrontational. Advocating for quality doesn’t mean being aggressive. The best testers build relationships that make quality everyone’s goal, not battles that position quality versus everything else.

You don’t need certifications. They don’t hurt, but they’re not necessary for being good at testing. What matters is what you can do, not what a certificate says you can do.

You don’t need to find every bug. Perfectionism is the enemy of effective testing. Good testers find the bugs that matter, not every bug that exists. Accepting that some bugs will escape is part of professional maturity.

You don’t need to be right all the time. You’ll raise concerns about bugs that turn out not to matter. You’ll miss bugs that turn out to be critical. You’ll make wrong predictions about risk. That’s normal. What matters is learning from these experiences and improving your judgment over time.

The Traits in Combination

Individual traits matter, but it’s the combination that creates exceptional testers.

Curiosity without skepticism leads to accepting interesting explanations without verifying them.

Skepticism without empathy leads to dismissing user concerns because “they’re doing it wrong.”

Attention to detail without analytical thinking leads to lists of observations without insight about what they mean.

Persistence without comfort with ambiguity leads to paralysis when facing unclear situations.

Communication skills without domain knowledge leads to clear reports about the wrong things.

The goal isn’t maximizing each trait independently — it’s developing a balanced combination that works together. Your specific balance might look different than another great tester’s balance. Some exceptional testers are highly technical; others are highly empathetic. Some are deeply curious; others are relentlessly persistent. There are many ways to be good at testing.

Growing Into a Better Tester

If you’ve assessed yourself against these skills and traits and found gaps, good. That awareness is where growth starts.

For skill gaps: Create a deliberate learning plan. Technical literacy can be improved through courses and practice. Domain knowledge builds through study and conversation. Communication skills develop through practice and feedback. Test design improves by studying techniques and applying them consciously.

For mindset gaps: These are harder because they require changing how you think, not just what you know. But it’s possible. Curiosity can be cultivated by deliberately asking questions. Skepticism can be developed by practicing verification. Attention to detail improves with slowing down and checklists. Empathy grows through exposure to users. Persistence strengthens through practice with hard problems.

For both: Find mentors and examples. Watch how good testers work. Ask them to explain their thinking. Study their bug reports. Notice how they approach problems differently than you do.

And give yourself time. These skills and traits develop over years, not weeks. The journey from adequate to good to great takes deliberate effort sustained over a long period.

Recognizing Good Testers

If you’re building a testing team or evaluating testing candidates, how do you recognize these traits?

Ask about discoveries. “Tell me about a bug you found that was particularly interesting or difficult.” Good testers light up when discussing discoveries. They explain not just what they found but how they found it, what made it challenging, and what they learned.

Watch them test. Give candidates a system and time to explore it. Observe their approach. Do they jump randomly or explore systematically? Do they ask questions? Do they notice things? Do they investigate or just move on?

Discuss ambiguous situations. Present scenarios with incomplete information. See how they handle uncertainty. Do they freeze? Make reasonable assumptions? Ask clarifying questions?

Review their communication. Look at bug reports they’ve written. Are they clear? Complete? Actionable? Do they communicate impact effectively?

Ask about failures. “Tell me about a bug you missed that caused problems.” Good testers have these stories and have learned from them. Testers who claim to never miss anything important are either lying or haven’t been tested enough to know better.

Your Self-Assessment

Time to turn this inward. Honestly evaluate yourself against the skills and mindsets we’ve discussed.

Rate yourself on each skill (1–5):

Technical literacy

Domain knowledge

Communication skills

Analytical thinking

Test design

Tool proficiency

Rate yourself on each mindset trait (1–5):

Curiosity

Skepticism

Attention to detail

Empathy

Persistence

Comfort with ambiguity

Now identify your biggest gap — the area where improvement would make the most difference in your effectiveness.

Create one specific action you’ll take this week to address that gap. Not a vague intention. A specific action with a deadline.

Then do it.

The Good Tester’s Identity

Being a good tester isn’t about job titles or certifications or years of experience. It’s about how you approach the work.

Good testers are relentlessly curious about how things work and why they fail.

Good testers verify rather than assume, question rather than accept.

Good testers notice what others miss and investigate when others move on.

Good testers think about users as real people, not abstract personas.

Good testers communicate clearly enough that their discoveries lead to action.

Good testers keep going when problems are hard and answers are elusive.

Good testers function effectively even when information is incomplete and expectations are unclear.

This combination is rare enough to be valuable and common enough to be achievable. Testing needs more people who develop these skills and nurture these mindsets.

In our next article, we’ll explore Building a Testing Mindset — practical exercises and habits for developing the questioning, skeptical, exploratory thinking that good testing requires. We’ll take the mindset traits we discussed today and turn them into daily practices.

Remember: What makes a good tester isn’t credentials or certifications. It’s the combination of skills you develop and the mindset you bring to every testing situation.

Strong articel on the combinatorial nature of testing traits. The perspective-switching framework is underrated, most testers get stuck in one view and miss bugs obvious from another angle. I've seen this play out where highly technical testers obsess over edge cases but miss basic usability issues users hit on day one. The barista example hits home,sometimes domain empathy beats credentials.