Verification vs Validation

"Are we building it right?" vs "Are we building the right thing?"

Welcome back to NextGen QA! Today we’re tackling one of the most frequently confused pairs of concepts in software testing — verification and validation. These two terms get mixed up so often that even experienced professionals sometimes use them interchangeably.

They’re not the same. And understanding the difference could save your project — or even lives.

Let me tell you about a spacecraft, a radiation machine, and an airplane. Each represents billions of dollars and, tragically, human lives lost because teams got this distinction wrong.

The $327 Million Mission

On September 23, 1999, NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter — a $125 million spacecraft at the center of a $327 million mission — approached Mars after a nine-month journey across 416 million miles of space. Everything had been tested. Every system had been verified against specifications. The software performed exactly as designed.

Then the spacecraft disappeared.

The investigation revealed something both simple and devastating: Lockheed Martin’s ground software calculated thrust in pound-force seconds. NASA’s systems expected newton-seconds. Nobody caught the mismatch. The orbiter flew too close to Mars and burned up in the atmosphere.

Here’s what’s crucial to understand: The software passed verification. It did exactly what the specifications said it should do. The Lockheed Martin code correctly calculated values in imperial units, precisely as its specifications defined.

But it failed validation. The system didn’t meet the actual mission need — navigating a spacecraft to Mars orbit. The specification itself was wrong, or at least, incomplete.

This is the heart of verification vs validation. One checks if you followed the recipe. The other checks if the cake actually tastes good.

The Definitions That Matter

Let me give you the formal definitions, then make them practical.

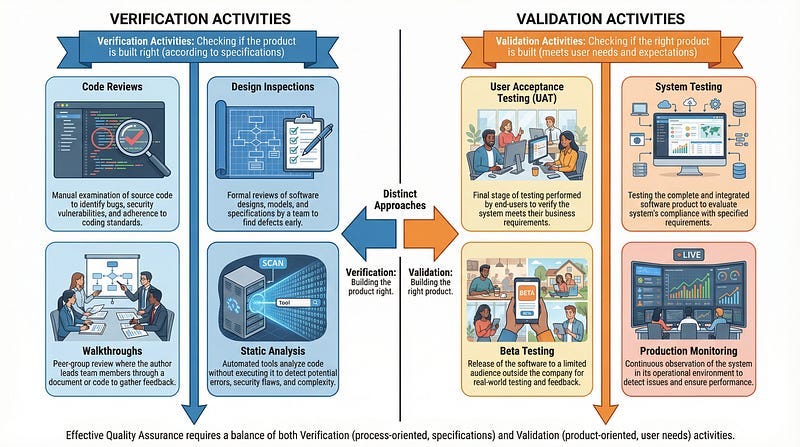

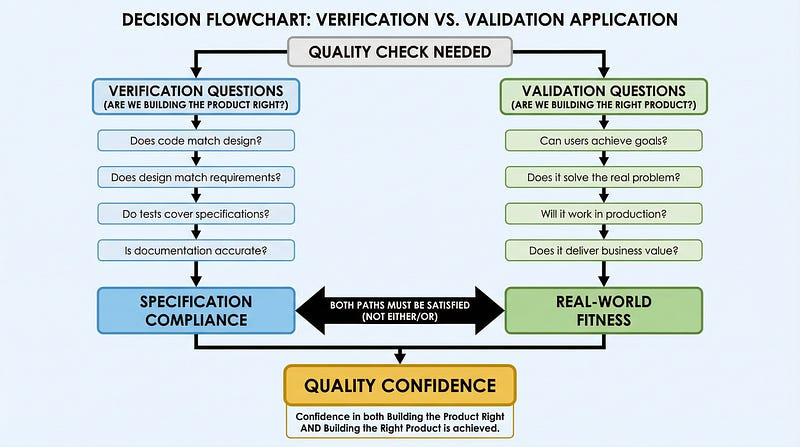

Verification answers: ”Are we building the product right?”

It’s the process of evaluating work products to determine whether they correctly implement the specified requirements. Think of it as checking your work against the blueprint. Did you build what the design said to build?

Validation answers: ”Are we building the right product?”

It’s the process of evaluating the final product to determine whether it satisfies the intended use and user needs. Think of it as checking whether what you built actually solves the problem it was meant to solve.

These definitions come from Barry Boehm, who articulated them in 1979, and they’ve been formalized in IEEE 1012 and ISTQB standards ever since. The words themselves hint at their meaning — verification shares a root with veritas (truth to specification), while validation comes from valere (to be worthy of use).

A Tale of Two Failures

Let me contrast two disasters that illustrate each type of failure.

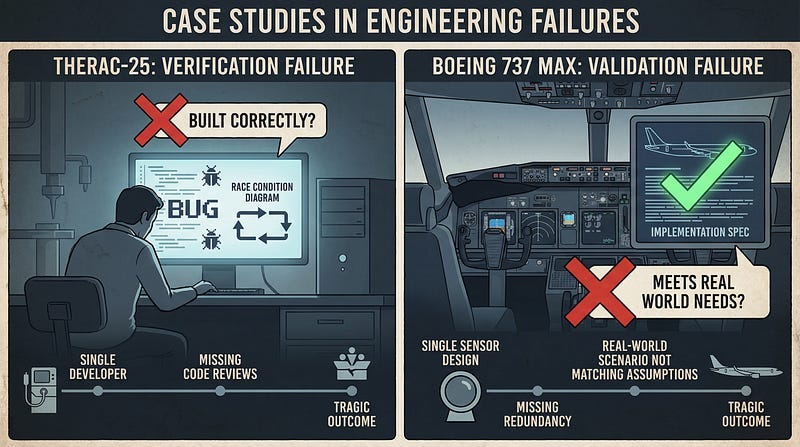

When Verification Fails: Therac-25

Between 1985 and 1987, the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine delivered lethal radiation doses to at least six patients, killing at least three. The cause? Race conditions in the software — timing bugs that occurred when operators typed commands faster than the system expected.

This was a verification failure. The software didn’t even meet its own specifications. Basic concurrent programming errors existed in code that had never been properly reviewed. The software was developed by one person over several years with no peer review. It was never considered during safety assessment — only hardware was tested.

The code was simply wrong. It didn’t do what it was supposed to do.

When Validation Fails: Boeing 737 MAX MCAS

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) on the Boeing 737 MAX worked exactly as designed. When angle-of-attack sensors indicated the nose was too high, it pushed the nose down. The code had no bugs. It passed every verification check.

But the design failed to account for what happens when a sensor fails. MCAS relied on a single sensor with no redundancy. When that sensor gave false readings on Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, the system repeatedly pushed the nose down, fighting the pilots until both aircraft crashed. 346 people died.

This was a validation failure. The software did exactly what it was designed to do. But what it was designed to do wasn’t what users actually needed in the real world. The specification itself was inadequate.

The Methods Behind Each

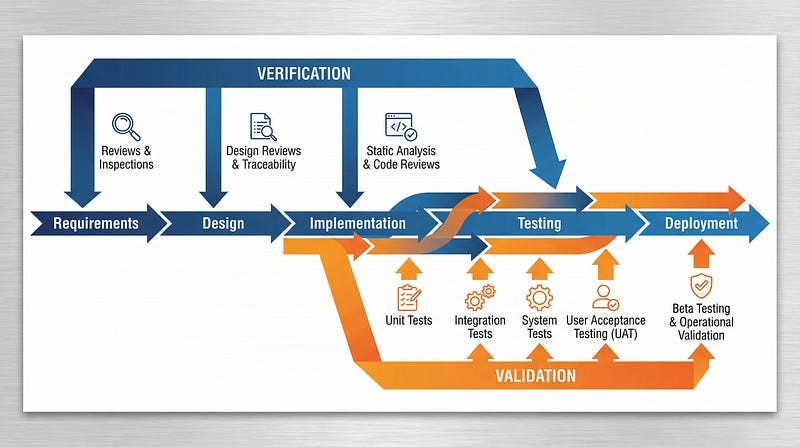

Verification and validation don’t just differ in what they check — they differ in how they check it.

Verification Methods (Static Testing)

Verification often happens without executing the software. It’s about examining artifacts:

Reviews and Inspections — Teams examine requirements, designs, and code against specifications. Does the architecture document address all requirements? Does the code implement the design correctly? These structured examinations catch errors before they become bugs.

Walkthroughs — Authors guide reviewers through their work, explaining decisions and receiving feedback. Less formal than inspections, but effective for knowledge sharing and catching assumptions.

Static Analysis — Automated tools examine code without running it, finding potential bugs, security vulnerabilities, and style violations. The code doesn’t need to execute for the tool to identify that a variable might be null when dereferenced.

Traceability Analysis — Checking that every requirement maps to design elements, code, and tests. If a requirement exists, something should implement it, and something should test it.

Verification asks: ”According to our plans, is this correct?”

Validation Methods (Dynamic Testing)

Validation requires running the software and observing its behavior in conditions that resemble real use. Note that dynamic testing methods can serve both verification and validation purposes — unit tests can verify code against design specs, while acceptance tests validate against user needs. The key is the perspective: are you checking against specifications, or against real-world fitness?

Unit Testing — Individual components are tested in isolation. Does this function return the expected output for given inputs?

Integration Testing — Combined components are tested together. Do these modules communicate correctly?

System Testing — The complete system is tested end-to-end. Does the whole application work as intended?

User Acceptance Testing — Real users (or their representatives) test the system. Does this actually solve their problem? Can they accomplish their goals?

Beta Testing — The product goes to a subset of real users in real environments. What happens when the software meets the chaos of the real world?

Validation asks: ”In practice, does this work?”

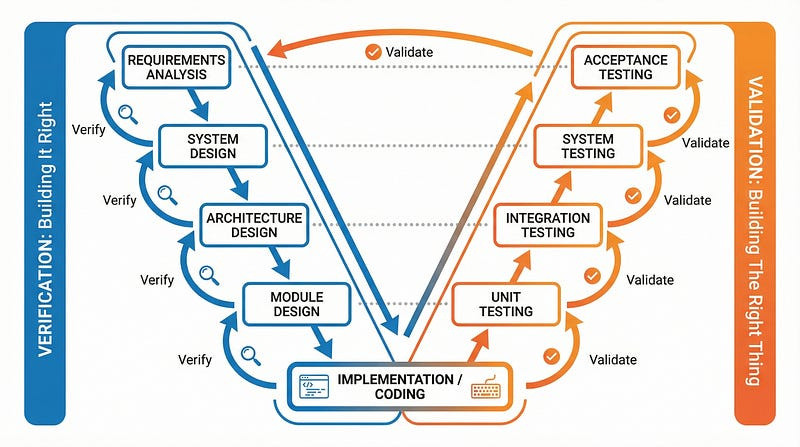

The V-Model Makes It Visual

If you want to see verification and validation in perfect architectural form, look at the V-Model — a software development approach that pairs each development phase with a corresponding testing phase.

On the left side of the V, you descend through requirements, system design, architecture design, and module design. On the right side, you ascend through unit testing, integration testing, system testing, and acceptance testing.

Here’s the insight: The left side is primarily about verification. You’re checking each level against the level above it. Does the design correctly capture the requirements? Does the architecture correctly implement the design?

The right side is primarily about validation. You’re checking each level against actual behavior. Does the unit perform correctly? Does the integrated system behave as users expect?

The V-Model makes visible what should be true in any methodology: verification and validation are complementary activities that run throughout development, not just a checkbox at the end.

Common Misconceptions

Let me address the myths I encounter constantly.

Myth 1: “They’re basically the same thing”

No. A system can pass all verification checks while completely failing validation (Boeing 737 MAX). It followed the spec perfectly — the spec was just wrong. Conversely, a system can satisfy users while violating specifications, though this creates technical debt and maintenance nightmares.

Myth 2: “Verification happens first, then validation”

While it’s true that verification tends to occur earlier (you can review requirements before you have running code), both activities should occur throughout development. In agile environments especially, you’re continuously both verifying (is this sprint’s work correct?) and validating (does it still serve user needs?).

Myth 3: “Thorough verification eliminates the need for validation”

The Mars Climate Orbiter proves this wrong. Every line of code worked as specified. The software was *verified* extensively. But it failed *validation* because the specifications didn’t capture what was actually needed. Verification can only be as good as the specifications it checks against.

Myth 4: “Validation only happens at the end”

Early validation catches wrong assumptions before you’ve invested months building the wrong thing. Prototypes, user feedback sessions, and MVP testing are all validation activities that smart teams do early and often.

Myth 5: “These are just tester activities”

Verification often involves developers reviewing each other’s code, architects inspecting designs, and business analysts validating requirements with stakeholders. Validation involves product owners, users, and business representatives. Both are team responsibilities, not just testing team responsibilities.

A Practical Framework

Here’s how I think about applying V&V in practice:

Ask two questions constantly:

1. ”Does this match our specification?” (Verification)

Code review: Does this implementation match the design?

Test review: Do these tests cover the requirements?

Documentation review: Does this describe what we actually built?

2. ”Does this solve the real problem?” (Validation)

User testing: Can people accomplish their goals?

Production monitoring: Is the system actually being used as intended?

Business metrics: Are we achieving the outcomes we wanted?

If you only ask the first question, you might build the wrong thing perfectly. If you only ask the second question, you might build the right thing poorly. You need both.

Industry Standards Require Both

If you work in regulated industries, you don’t get to choose whether to do V&V — standards mandate both.

Medical Devices (FDA 21 CFR Part 820)

The FDA requires documented verification and validation for medical device software. Section 820.30(g) specifically addresses software validation. You must prove the software was built correctly (verification) AND that it meets user needs safely (validation). The consequences of getting this wrong are measured in patient harm.

Aerospace (DO-178C)

Software in aircraft must meet Design Assurance Levels (DAL) ranging from E (no safety effect) to A (catastrophic failure potential). Level A software requires completing 71 verification objectives. Coverage requirements include statement coverage, branch coverage, and modified condition/decision coverage (MC/DC). Independence is mandatory — the person who wrote the code cannot be the only person who verifies it.

Automotive (ISO 26262)

Automotive Safety Integrity Levels (ASIL A through D) determine how rigorously you must verify and validate. ASIL D systems — where failure could be fatal — require the most extensive V&V, including formal verification methods.

These standards exist because verification alone isn’t enough. A perfectly verified specification that doesn’t account for real-world conditions kills people, as Boeing painfully demonstrated.

AI and the Trust-But-Verify Principle

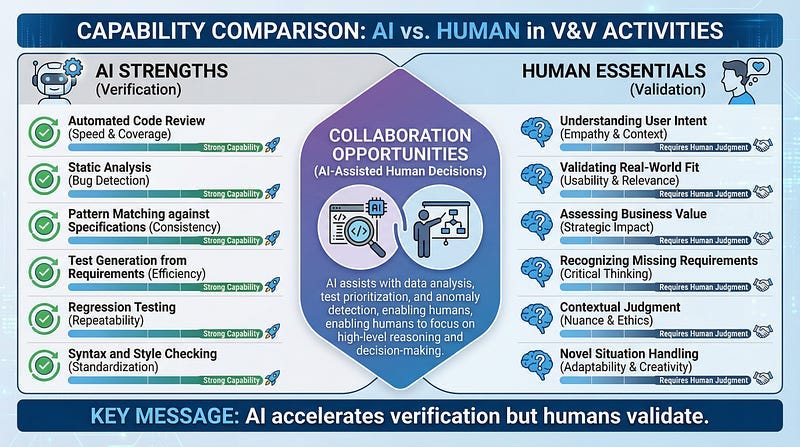

Here’s where this connects to our broader theme of AI in testing.

AI tools can generate test cases, suggest code, and automate many verification activities. But recent industry data reveals a troubling trend: developer trust in AI outputs has dropped from 43% to 33% in just one year.

Why? The “almost right” problem.

66% of developers report that AI-generated code is “nearly correct” — close enough to look good, different enough to be dangerous. Studies show 40–48% of AI-generated code contains security vulnerabilities. This creates what I call verification debt — code that looks right but hasn’t been properly checked.

Here’s the insight: AI struggles more with validation than verification.

AI can check if code follows patterns, matches specifications, and avoids known bad practices. That’s verification, and AI can help significantly.

But AI struggles to know if the specification itself is right. It can’t tell if users will actually find the feature useful. It can’t sense that the requirements missed an edge case that matters in production. That requires human judgment about real-world context.

The “trust but verify” principle becomes crucial: Use AI to accelerate verification activities, but maintain human judgment for validation activities. AI can help you build it right. Only humans can determine if you’re building the right thing.

Your Verification & Validation Checklist

Let me leave you with practical guidance.

For Verification, ask:

Have requirements been reviewed for completeness and consistency

Has the design been reviewed against requirements?

Has code been reviewed against the design?

Have test cases been reviewed against requirements?

Has static analysis been run on the code?

Is there traceability from requirements to tests?

Have all findings from reviews been addressed?

For Validation, ask:

Have real users (or realistic proxies) tested the system?

Does the system work in conditions resembling production?

Can users accomplish their actual goals?

Does the system handle realistic error conditions?

Have edge cases from real-world scenarios been tested?

Does the system deliver the intended business value?

Would you trust this system with real stakes?

If you’re checking boxes only in the first list, you might be building the wrong thing perfectly. If you’re checking boxes only in the second list, you might be building the right thing poorly.

Do both.

Verification and validation are two lenses for examining quality. Verification asks whether you followed the plan. Validation asks whether the plan was right.

The Mars Climate Orbiter followed its plan perfectly into the wrong trajectory. The Boeing 737 MAX MCAS executed its design flawlessly into disaster. These weren’t failures of execution — they were failures of validation. The specifications themselves were wrong, and no amount of verification against wrong specifications can make a product right.

Conversely, the Therac-25 didn’t even follow its specifications correctly. Race conditions and untested code paths represented fundamental verification failures. Even if the design had been perfect, the implementation was broken.

You need both. Always.

In our next article, we’ll explore Static vs Dynamic Testing — diving deeper into the techniques that make verification and validation work in practice. We’ll look at how finding defects without executing code complements finding them through execution.

Until then, remember:

Building it right isn’t enough if you’re not building the right thing. And building the right thing doesn’t matter if you can’t build it right.