Understanding Test Objectives

Aligning testing with business goals

Here’s a question that should be simple but rarely is: Why are you testing?

Most testers answer reflexively: “To find bugs.” And yes, finding defects is part of testing. But it’s not the objective of testing — it’s a method of achieving objectives. The difference matters enormously.

I once watched two testers work on the same release with completely different outcomes, even though both found similar numbers of bugs. The first tester found twenty-three defects, logged them all, and called it a successful test cycle. The second tester found nineteen defects, but also provided a risk assessment, identified the critical user journeys that were now solid, flagged areas that still needed attention, and gave clear guidance on release readiness.

Guess which tester the product manager trusted more? Guess which tester influenced decisions? Guess which tester actually impacted quality?

Finding bugs is easy. Understanding why you’re testing, what really matters, and how your testing serves business objectives — that’s where professional testing begins.

What Are Test Objectives?

Test objectives are the specific, measurable goals your testing aims to achieve. They answer fundamental questions: What are we trying to learn? What decisions does this testing inform? What risks are we evaluating? What confidence are we building?

Good test objectives connect testing activities to business outcomes. They’re specific enough to guide your testing approach but flexible enough to adapt as you learn. They’re shared across the team so everyone understands what testing is actually trying to accomplish.

Bad test objectives are vague platitudes like “ensure quality” or “find all bugs” or “make sure it works.” These sound reasonable but provide zero guidance. How do you know when you’ve ensured quality? What does “all bugs” mean when exhaustive testing is impossible? What does “works” mean without context?

Here’s the difference:

Vague objective: “Test the login feature.”

Clear objective: “Verify that users can successfully authenticate using the three supported methods (email/password, social login, SSO) and that security controls prevent unauthorized access, with focus on the most common authentication flows since this is the entry point for all users.”

The clear objective tells you what to prioritize, why it matters, and what “done” looks like.

Common Testing Objectives (And What They Really Mean)

Let’s break down the most common testing objectives and what they actually entail when you think beyond surface level.

Finding Defects Before Users Do

This is the most obvious objective, but it’s more nuanced than it appears. You’re not trying to find all bugs — that’s impossible. You’re trying to find bugs that matter before they impact users.

This objective drives you toward risk-based testing, toward focusing on critical user paths, toward understanding which bugs are worth delaying release and which can wait. It means asking “what bugs would cause the most damage if they reached production?” and hunting specifically for those.

Finding a hundred cosmetic bugs while missing one data corruption bug means you failed this objective despite your impressive bug count.

Assessing Release Readiness

Sometimes testing isn’t about finding every bug — it’s about providing information so stakeholders can decide whether to release. This objective shifts your focus from defect hunting to risk assessment.

You’re answering: Are critical features stable? Have we tested the high-risk areas adequately? What are the known issues and how severe are they? What’s the likelihood of major problems in production? What’s our confidence level?

This objective requires communication skills as much as testing skills. You’re providing decision-making information, not just bug reports.

Validating Requirements and Specifications

Early in projects, testing objectives often focus on whether requirements are clear, complete, testable, and sensible. You’re not testing code yet — you’re testing documentation and specifications.

This objective catches problems when they’re cheapest to fix. Finding ambiguous requirements during planning costs nothing. Finding them when users complain about confusing features costs everything.

Building Confidence in Stability

For mature products with established user bases, a major testing objective is confirming that changes haven’t broken existing functionality. You’re not expecting to find dramatic new bugs — you’re verifying that what worked yesterday still works today.

This objective drives heavy investment in regression testing and automation. It’s about risk management and maintaining trust.

Exploring Unknown Risks

Sometimes testing objectives are explicitly exploratory: we don’t know what we don’t know, and we need to discover risks we haven’t anticipated. This is less about executing test cases and more about learning through interaction.

This objective requires curiosity, creativity, and tolerance for uncertainty. Success isn’t measured in bugs found per hour — it’s measured in insights gained and hidden risks revealed.

Verifying Performance and Scalability

When your objective is understanding how the system behaves under load, stress, or resource constraints, your testing approach changes completely. You’re not looking for functional bugs — you’re measuring behavior under specific conditions.

This objective requires different tools, different expertise, and different success criteria. “It works” isn’t enough. “It works for 10,000 concurrent users with average response time under 2 seconds” is the target.

Ensuring Security and Compliance

Testing with security objectives means thinking like an attacker. You’re not just checking that features work — you’re trying to break security controls, exploit vulnerabilities, and bypass protections.

Compliance objectives mean verifying that software meets regulatory requirements, industry standards, and legal obligations. The objective is documentation and proof as much as defect detection.

Validating User Experience

When your objective is ensuring users can successfully accomplish their goals with the software, you’re testing usability, clarity, and satisfaction — not just functionality.

This objective pulls you out of the test lab and puts you in front of real users watching real attempts to use the software. Success means users succeed, not that tests pass.

How Objectives Shape Your Entire Testing Approach

Your test objectives aren’t just abstract goals — they fundamentally change how you test. Let me show you with a concrete example.

Imagine you’re testing a new feature: users can export their data to CSV format. Depending on your objective, you test completely differently.

If your objective is finding defects: You focus on breaking the export. What happens with empty datasets? What if someone exports while data is being modified? What if the file name contains special characters? What about extremely large datasets? You’re deliberately trying to make things fail.

If your objective is release readiness: You focus on critical scenarios working reliably. Can users successfully export typical datasets? Does the exported data match what’s in the system? Are error messages clear if something goes wrong? You’re building confidence in common cases, not hunting edge cases.

If your objective is validating requirements: You check whether the implementation matches specifications. Does the CSV format match requirements? Are all specified fields included? Does the feature handle the requirements-defined data limits? You’re verifying contract fulfillment.

If your objective is user experience: You test whether users can figure out how to export without help. Is the export button obvious? Is the process intuitive? Do users understand what they’re getting? You’re evaluating usability and clarity.

If your objective is performance: You measure how long exports take with various dataset sizes. Can the system handle multiple simultaneous exports? Does export performance degrade under load? You’re quantifying behavior, not just checking correctness.

If your objective is security: You test whether users can export data they shouldn’t access. Can export be used to bypass access controls? Could exported files contain sensitive data that should be filtered? You’re thinking about malicious use and unauthorized access.

Same feature. Six completely different testing approaches. All valid. All useful. But only if you’re clear about which objective you’re pursuing when.

Testing everything six ways is exhaustive testing (which we know is impossible). Understanding your objective lets you test the right way for your current goal.

The Conversation You Should Have (But Probably Aren’t)

Here’s what amazes me: teams spend hours planning sprints, reviewing requirements, and estimating development effort. Then when it comes to testing, someone says “okay, test it” and expects the tester to figure out what that means.

This is backwards. Before you write a single test case, you should have an explicit conversation about test objectives.

Questions to ask stakeholders:

“What decisions will this testing inform? Are we deciding whether to release, or confirming features work as expected, or exploring potential risks?”

“What would make you confident enough to ship? Is it zero high-severity bugs, or successful validation of critical user paths, or specific performance benchmarks?”

“What are the biggest risks you’re worried about? Security vulnerabilities, user confusion, performance problems, integration failures, data corruption?”

“Who are we testing for? Internal QA validation, user acceptance, regulatory compliance, all three?”

“What does success look like? How will we know when we’ve tested enough?”

These conversations surface assumptions, align expectations, and clarify priorities. They prevent the situation where you spend two weeks finding fifty cosmetic bugs while the product manager was losing sleep about a potential security vulnerability you never tested because you didn’t know it mattered.

Questions to ask yourself:

“Why does this specific feature exist? What user problem does it solve?”

“If I could only test three things about this feature, which three would matter most?”

“What’s the worst that could happen if this feature had bugs? Who would be affected and how?”

“What does the business care most about — speed to market, zero defects, user satisfaction, competitive feature parity?”

Your testing should have clear, explicit answers to these questions. If you don’t, you’re testing without objectives — just going through motions hoping to stumble onto something useful.

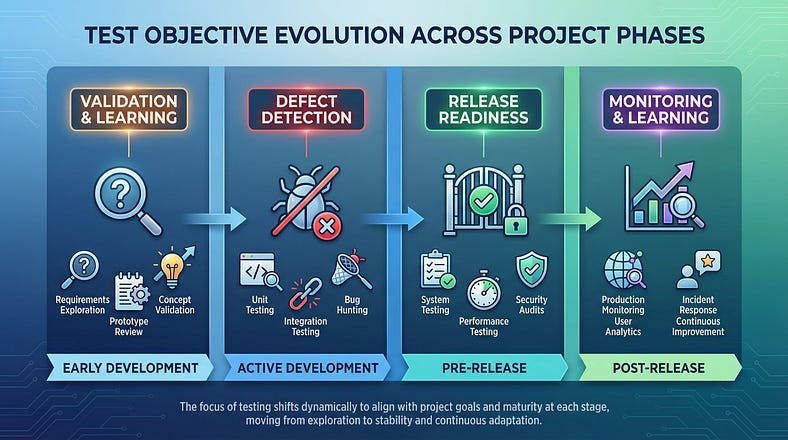

Objectives Change Across the Project Lifecycle

Test objectives aren’t static. They evolve as projects progress through different phases.

Early Development: Learning and Validation

Early in development, objectives focus on validating direction. Does this technical approach work? Are requirements sensible and testable? Can we build what’s being specified? Testing is exploratory and hypothesis-testing.

You’re not expecting polished features. You’re checking feasibility, catching misaligned expectations, and providing early feedback when changes are cheap.

Active Development: Defect Detection and Quality Guidance

Mid-project, objectives shift toward finding defects in actively developed code and guiding developers toward quality. You’re testing new features as they’re built, catching bugs while context is fresh, and providing rapid feedback loops.

You’re also assessing whether quality is trending up or down. Are bugs decreasing as code stabilizes, or are new features introducing more problems than are being fixed?

Pre-Release: Release Readiness and Risk Assessment

As release approaches, objectives shift toward release decisions. Testing focuses on critical paths, integration stability, and overall system health. You’re less focused on finding minor bugs and more focused on assessing major risks.

Your primary deliverable isn’t a bug list — it’s a recommendation: “Are we ready to release? What are the known risks? What’s our confidence level?”

Post-Release: Validation and Learning

After release, testing objectives focus on validating the release succeeded and learning from production behavior. Did users encounter issues we missed? How is the software performing under real load? What should we test differently next time?

Production monitoring becomes a testing activity. User feedback becomes test input. Lessons learned inform future test objectives.

Trying to use the same testing approach across all these phases misses the point. Objectives change. Testing must adapt accordingly.

When Objectives Conflict (And How to Handle It)

Sometimes you face multiple testing objectives that pull in different directions. How do you resolve these tensions?

Speed versus Thoroughness

The business wants to release quickly. Quality wants comprehensive testing. These objectives conflict.

Resolution: Get explicit about risk tolerance. What level of defects is acceptable given the business context? What areas absolutely must be solid versus where minor issues are tolerable? Time-box testing based on agreed priorities.

Coverage versus Depth

You could test many features superficially or few features deeply. Both are valid objectives, but you can’t do both with limited time.

Resolution: Apply risk-based thinking. Test high-risk features deeply. Test medium-risk features adequately. Test low-risk features lightly. Document your coverage decisions so they’re conscious choices, not accidental gaps.

Finding Bugs versus Building Confidence

Aggressive testing finds more bugs but might undermine stakeholder confidence. Conservative testing builds confidence but might miss issues.

Resolution: Separate exploratory testing from validation testing. Use exploratory sessions to hunt bugs aggressively. Use scripted tests to demonstrate that critical paths work reliably. Both serve important but different objectives.

Testing for Now versus Testing for Later

Do you optimize testing for the current release or build regression suites for future releases? Both require time and effort.

Resolution: Balance based on product maturity. New products need more current-release testing. Mature products need stronger regression protection. Explicitly allocate time to both.

The key is making these trade-offs consciously and transparently based on articulated objectives, not just defaulting to whatever you’ve always done.

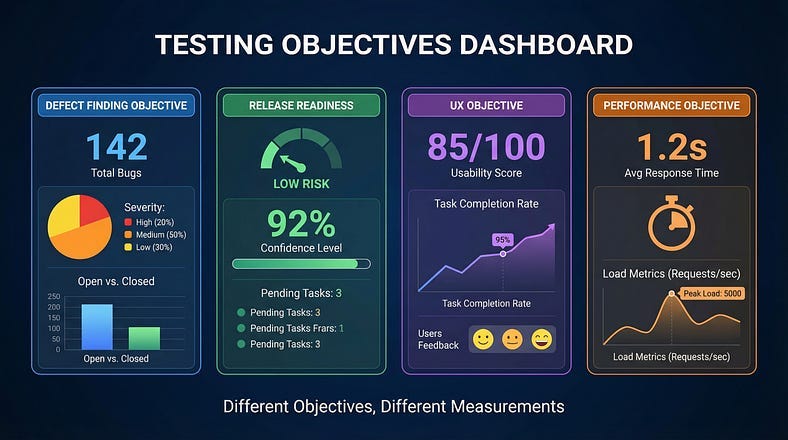

Measuring Success Against Objectives

How do you know if you’ve achieved your test objectives? You need metrics that align with your stated goals.

If your objective is finding defects: Track bugs found, severity distribution, defect detection rate over time. Success means finding significant issues before they impact users.

If your objective is release readiness: Track test execution completion, critical path validation, risk assessment confidence. Success means stakeholders have the information they need to make release decisions.

If your objective is stability: Track regression test pass rates, production incident rates, mean time between failures. Success means stable, predictable behavior.

If your objective is user experience: Track usability test success rates, task completion times, user satisfaction scores. Success means users can accomplish goals efficiently and happily.

Don’t use defect counts as your only metric if defect detection isn’t your primary objective. Don’t celebrate 100% test execution if execution wasn’t the point — learning was. Match your metrics to your objectives.

And be honest about what metrics can’t tell you. High test coverage doesn’t guarantee quality. Low defect counts might mean inadequate testing rather than excellent code. Zero production incidents could mean no one’s using the product. Numbers need context.

The Role of Test Plans and Test Strategies

Test plans and strategies should start with objectives, not activities. Yet most test plans I see begin with “Test Approach” and “Test Cases” without ever articulating why they’re testing or what they hope to achieve.

A test strategy informed by clear objectives might say:

“Our primary objective is assessing release readiness for the Q3 launch. Given our aggressive timeline and established user base, we will focus 60% of effort on regression testing to maintain stability, 30% on new feature validation to ensure core functionality works, and 10% on exploratory testing to catch unexpected issues. We will not conduct extensive performance testing this cycle since the new features don’t significantly impact load — that’s deferred to Q4. Success means completing critical path validation with zero high-severity bugs in core workflows and a documented risk assessment for known moderate and low-severity issues.”

That paragraph tells you everything about what testing will focus on and why. It makes trade-offs explicit. It sets clear success criteria. It aligns testing with business reality.

Compare that to: “We will test all features thoroughly using manual and automated testing to ensure quality.”

Which one actually guides testing? Which one helps when you’re forced to cut scope? Which one explains to stakeholders what you’re doing and why?

Write your test objectives first. Then let those objectives shape your strategy, your approach, your resource allocation, and your success criteria.

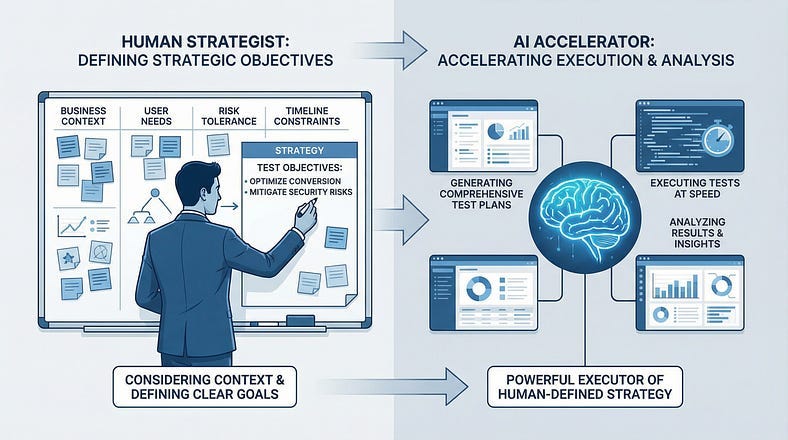

AI’s Blindspot: Understanding Business Context

AI can help execute testing once objectives are clear. It can generate test cases, automate execution, analyze results, identify patterns. But AI struggles enormously with understanding business context that shapes objectives.

AI doesn’t know whether your company prioritizes speed over perfection or perfection over speed. It doesn’t understand that your biggest competitor just launched a similar feature, creating business pressure to release quickly. It doesn’t grasp that a recent security breach has made security testing the top priority. It can’t sense organizational politics that make certain stakeholders’ concerns more influential than others.

These contextual factors shape test objectives profoundly. AI can’t determine them. You must.

Use AI to accelerate testing once you’ve defined clear objectives. Let AI generate test variations, execute repetitive tests, analyze large result sets. But don’t outsource the strategic thinking about why you’re testing and what matters most. That requires human judgment informed by business context.

AI excels at: “Given this test objective, here are 100 test scenarios that support it.”

AI fails at: “Given this business situation, here’s what your test objective should be.”

That second capability — strategic objective setting — is irreplaceably human.

Objectives for Different Project Types

Test objectives vary dramatically based on project context. Let’s look at how objectives shift across different scenarios.

Startup MVP: Primary objective is validating product-market fit quickly. Testing focuses on core value proposition working adequately. Secondary objectives like polish, edge cases, and comprehensive coverage are explicitly deprioritized. Speed and learning matter more than perfection.

Enterprise System Migration: Primary objective is ensuring existing functionality continues working. Testing focuses heavily on regression, data migration accuracy, and integration stability. Finding new bugs is less important than verifying nothing breaks during the transition.

Regulatory Compliance Update: Primary objective is proving compliance with new regulations. Testing focuses on documenting that requirements are met and creating audit trails. The objective is as much about documentation and proof as finding defects.

Performance Optimization Release: Primary objective is validating improvements without regression. Testing focuses on measuring performance metrics and confirming optimization worked while ensuring functionality didn’t break.

Security Patch: Primary objective is confirming vulnerability is fixed without introducing new issues. Testing focuses narrowly on security validation and immediate regression, with broad testing deferred to next release.

Context shapes objectives. Objectives shape testing. Don’t use the same testing approach regardless of context.

Your Assignment

First, articulate your current test objectives explicitly. Write them down. For your current project or sprint, complete this sentence: “The primary objective of testing this [feature/release/sprint] is to _____ because _____.” If you can’t complete it clearly, you’re testing without direction.

Second, evaluate alignment. Look at what you’re actually testing and how you’re spending time. Does your actual testing activity align with your stated objectives? If you say your objective is release readiness but you’re spending eighty percent of time finding cosmetic bugs, there’s misalignment.

Third, have the objectives conversation. Schedule fifteen minutes with your product manager or key stakeholder. Ask explicitly: “What are the most important objectives for testing this release? What information do you need from testing to make decisions?” Compare their answers to your assumptions.

Fourth, adjust one thing. Based on clear objectives, change one aspect of your testing approach. Maybe you stop testing a low-priority area and focus more on a high-priority one. Maybe you add a specific type of testing that serves your objective better. Make one objective-driven adjustment.

Finally, measure differently. If your current metrics don’t align with your objectives, define one new metric that does. If your objective is user success but you’re measuring bug counts, start measuring task completion rates instead.

Testing With Purpose

Understanding test objectives transforms testing from activity into strategy. It’s the difference between finding bugs and achieving goals. It’s the difference between executing test cases and providing valuable information. It’s the difference between testing because that’s what testers do and testing because you know exactly what you’re trying to accomplish.

Every testing decision — what to test, how deeply to test it, which techniques to use, when to stop testing — becomes clearer when you have explicit objectives. You’re not guessing. You’re not following templates blindly. You’re making conscious choices in service of defined goals.

The most effective testers I know can articulate their testing objectives at any moment. They know why they’re testing each feature, what information they’re gathering, what decisions their testing informs. They test with purpose.

In our next article, we’ll explore The SDLC and Where Testing Fits — understanding how testing integrates across the entire software development lifecycle. This builds on test objectives because objectives change throughout the SDLC. Knowing where you are in the lifecycle helps you set appropriate testing objectives for that phase.

Testing without clear objectives is just going through motions. Define your objectives first. Let objectives drive everything else.

Couldn't agree more. It's wld how often the *why* gets lost. How do we fix that?

nice piece! though, at points a bit too general, even borderline BS, e.g. “2. if you could only test 3 things” or something like that. at best it answers the same question as before it: what does this feature do for the user.

I agree with much of the article, I think there’s too much repetition. I wrote a shorter list of my mental checks before testing.

https://open.substack.com/pub/zdengineering/p/8-years-of-testing-software-aka-the?r=4aoo46&utm_medium=ios&shareImageVariant=overlay

Also, verification and validation have meaning in testing context. I think sometimes you just use them as a synonym to “check”. While this also depends on context, I think you could be more mindful about it.