The Testing Mindset vs Development Mindset

Complementary perspectives on quality

I watched a developer and a tester argue for twenty minutes about whether something was a bug.

The developer built a form that accepted dates in MM/DD/YYYY format. The tester entered “13/45/2024” and the system crashed. Bug, right?

“That’s not a valid date,” the developer said. “No reasonable user would enter that.”

“But the system crashed,” the tester replied. “It should handle invalid input gracefully.”

They were both right. And they were talking past each other completely.

The developer was thinking about how the feature should work when used correctly. The tester was thinking about what happens when it’s used incorrectly. Neither perspective was wrong — they were just different lenses on the same reality.

This is the fundamental tension between the testing mindset and the development mindset. Not a conflict to be resolved, but a complementary pair that together creates better software than either could alone.

Today we’re exploring these two mindsets — how they differ, why they differ, and how understanding both makes you better at whichever role you occupy.

Two Valid Ways of Seeing

Let’s start with a fundamental truth: neither mindset is superior. They’re different tools for different jobs.

The development mindset is fundamentally constructive. Developers take requirements and transform them into working systems. They solve problems by building solutions. Their success is measured by creating something that works.

The testing mindset is fundamentally analytical. Testers take working systems and evaluate whether they actually meet needs. They find problems by examining solutions. Their success is measured by discovering what doesn’t work before users do.

Construction and analysis. Building and evaluating. Creating and questioning.

Software needs both. A team of only builders creates systems that work in ideal conditions but crumble under real-world stress. A team of only analysts never ships anything because there’s always another potential problem to investigate.

The magic happens when both mindsets collaborate — when builders and analysts work together toward shared quality goals.

The Core Differences

Let’s examine how these mindsets differ across several dimensions.

Relationship with Requirements

Development mindset: Requirements are a blueprint to implement. The goal is translating requirements into functioning code. Success means the code does what the requirements specify.

Testing mindset: Requirements are hypotheses to validate. The goal is determining whether the implementation actually meets user needs. Success means confirming the software works — or discovering where it doesn’t.

A developer reads a requirement and thinks: “How do I build this?”

A tester reads the same requirement and thinks: “How will I know if this actually works? What could go wrong? What’s ambiguous here?”

Same document, different questions.

Relationship with the Happy Path

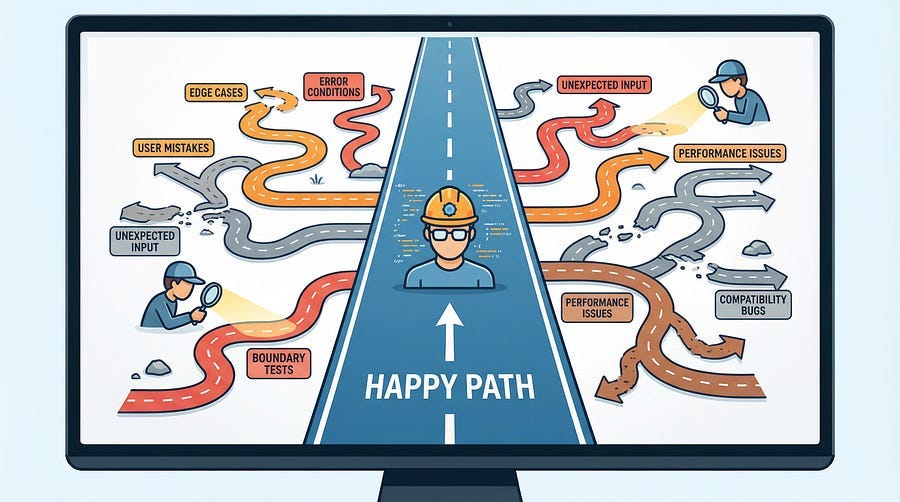

Development mindset: The happy path is the primary focus. If users do what they’re supposed to do, in the order they’re supposed to do it, with the data they’re supposed to use, everything works. The happy path is where developers spend most of their mental energy.

Testing mindset: The happy path is just the starting point. Of course it should work — but what about the sad paths? The angry paths? The confused paths? The malicious paths? Testers spend most of their mental energy on everything except the happy path.

This isn’t because developers don’t care about edge cases. It’s because building the happy path is genuinely hard and consumes significant cognitive resources. By the time it works, there’s often limited mental energy left for imagining all the ways users might deviate from the expected flow.

Testers arrive fresh, with full cognitive resources dedicated to asking “what if?”

Relationship with Their Own Work

Development mindset: Pride in creation. Developers invest significant intellectual and emotional energy in their code. They’ve solved hard problems, made difficult decisions, and crafted something that works. There’s natural ownership and attachment.

Testing mindset: Detachment for objectivity. Testers examine systems they didn’t build, which provides natural distance. They have no ego investment in the code working — their investment is in finding the truth about whether it works.

This difference explains why developers testing their own code often miss bugs that are obvious to others. It’s not incompetence — it’s human nature. We see what we expect to see, especially in things we created.

Relationship with Time

Development mindset: Forward momentum. Developers are measured by features completed, code shipped, problems solved. Progress means moving forward. Stopping to reconsider finished work feels like going backward.

Testing mindset: Deliberate examination. Testers are measured by issues found, confidence established, risks identified. Progress means thorough evaluation. Rushing past potential problems defeats the purpose.

This creates natural tension. Developers feel tested code is “done” and want to move on. Testers feel examined code needs more investigation. Both impulses are valid — the tension is productive when managed well.

Relationship with Failure

Development mindset: Failure is a problem to fix. When code doesn’t work, something is wrong. The goal is making it work. Failure is a temporary state on the path to success.

Testing mindset: Failure is information to capture. When software doesn’t work, something has been learned. The goal is documenting what happened, understanding why, and ensuring it gets addressed. Failure is valuable data.

A developer sees a crash and thinks: “I need to fix this.”

A tester sees the same crash and thinks: “I need to document this, understand the conditions that caused it, assess its severity, and verify it gets fixed.”

Why These Differences Exist

These mindset differences aren’t arbitrary. They emerge from the fundamentally different nature of the work.

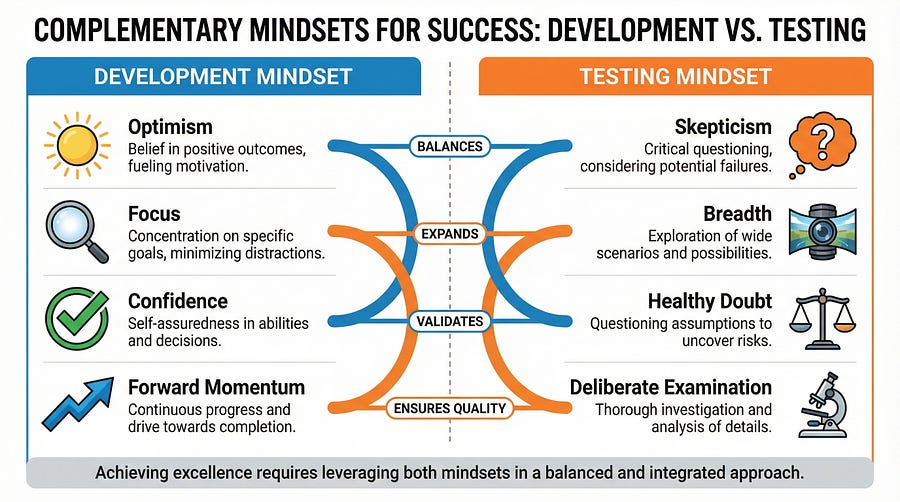

Building requires optimism. Creating something from nothing demands belief that problems can be solved, that the vision can become reality, that the complex pieces will eventually fit together. Pessimistic builders struggle to start — there are always reasons why something might not work.

Evaluating requires skepticism. Determining whether something actually works demands questioning assumptions, doubting claims, and looking for evidence of problems. Optimistic evaluators miss issues — they assume things work without verification.

Building requires focus. Developers hold enormous complexity in their heads — data structures, algorithms, state management, edge cases they’re handling. This focused attention is necessary for construction but leaves little room for imagining problems they haven’t anticipated.

Evaluating requires breadth. Testers consider many scenarios, user types, and failure modes. They can’t focus as deeply on any single area because their job is covering the entire surface.

Building requires confidence. Making hundreds of decisions about how to implement something demands confidence in your judgment. Second-guessing every choice would paralyze progress.

Evaluating requires doubt. Verifying those decisions are correct demands questioning them. Accepting every choice without investigation would miss problems.

Neither set of traits is better. They’re adapted to different functions.

The Blended Reality

Here’s where it gets nuanced: real people don’t fit neatly into one mindset.

Good developers do think about edge cases. They write unit tests. They consider what could go wrong. They’re not naive optimists who ignore potential problems.

Good testers do understand construction. They appreciate the difficulty of building software. They know why certain bugs happen. They’re not just destructive critics who tear things down.

The mindsets exist on a spectrum, and effective practitioners of either role can shift along that spectrum as needed.

But there’s a default mode — a home base where each role naturally lives. Developers default to constructive thinking and shift to analytical thinking when necessary. Testers default to analytical thinking and shift to constructive thinking when necessary.

And that default matters. When under pressure, people revert to their default. A developer under deadline pressure focuses on making things work, potentially cutting corners on edge case handling. A tester under pressure to approve a release focuses on finding problems, potentially raising issues that don’t matter much.

Understanding your default helps you compensate for its blind spots.

How Misunderstanding Creates Conflict

When developers and testers don’t understand each other’s mindsets, predictable conflicts emerge.

Developers see testers as obstacles. “They just find problems. They don’t understand how hard this was to build. They’re never satisfied.”

Testers see developers as careless. “They don’t think about edge cases. They just want to ship and move on. They don’t care about quality.”

Both perceptions are wrong. They’re what happens when different mindsets interpret each other through their own lens.

The developer’s desire to move forward isn’t carelessness — it’s appropriate focus on construction. The tester’s insistence on investigation isn’t obstruction — it’s appropriate focus on evaluation.

Conflict happens when neither side recognizes the other’s perspective as valid.

The developer who sees a bug report as an attack on their competence gets defensive. The tester who sees pushback on a bug as dismissing their expertise gets frustrated. Each interaction reinforces negative perceptions.

I’ve watched this spiral destroy team relationships. I’ve also watched teams transcend it by developing genuine appreciation for what the other mindset contributes.

The Developer Who Understands Testing

The best developers I’ve worked with have developed genuine testing intuition.

They think about edge cases before testers find them. They write comprehensive unit tests not because they’re required but because they want confidence in their code. They review their own work skeptically before calling it done. They appreciate bug reports as valuable information rather than personal criticism.

These developers haven’t abandoned the development mindset. They’ve expanded it. They can shift into analytical thinking when needed, then shift back to constructive thinking.

What does this look like in practice?

Before coding: They think about what could go wrong, what inputs might cause problems, what states might be invalid. They build defenses against problems they anticipate.

During coding: They test their own work continuously. Not formal testing — just constant verification that what they’re building actually works.

After coding: They review their implementation critically. They try to break it. They imagine how a tester would approach it and preemptively address obvious issues.

When bugs are found: They’re curious rather than defensive. “Interesting — I didn’t think about that scenario. Let me understand what happened.”

This isn’t about becoming a tester. It’s about incorporating testing thinking into development practice. The code that results is more robust, and the relationships with testers are more collaborative.

The Tester Who Understands Development

The best testers I’ve worked with have developed genuine development appreciation.

They understand why certain bugs happen. They know that some edge cases are genuinely hard to anticipate. They write bug reports that help developers fix issues rather than just documenting problems. They recognize the difference between carelessness and reasonable tradeoffs.

These testers haven’t abandoned the testing mindset. They’ve contextualized it. They can appreciate construction while still maintaining analytical rigor.

What does this look like in practice?

When exploring features: They think about how the feature was probably built. They target testing toward areas where bugs are likely based on implementation patterns.

When finding bugs: They investigate enough to provide useful information. Not just “it doesn’t work” but “here’s exactly what I did, here’s what I expected, here’s what happened, and here’s some initial investigation into what might be causing it.”

When reporting bugs: They frame issues in terms of user impact and business risk, not just technical problems. They prioritize ruthlessly rather than treating every issue as critical.

When discussing fixes: They engage constructively. They understand why some fixes are harder than they appear. They help developers understand the problem rather than just demanding solutions.

This isn’t about becoming a developer. It’s about incorporating development appreciation into testing practice. The bugs found are more valuable, and the relationships with developers are more collaborative.

Practical Bridges Between Mindsets

Understanding is good. Practical bridges are better. Here are specific practices that help mindsets collaborate effectively.

Three Amigos Sessions

Before development begins, three perspectives meet: product (what we need), development (how we’ll build it), and testing (how we’ll verify it). Each mindset contributes to shared understanding.

Testers ask questions that surface ambiguities and edge cases. Developers explain implementation approaches that inform testing strategy. Product clarifies intent behind requirements.

This isn’t a meeting where testers find problems with developer plans. It’s a conversation where different perspectives combine to create better plans.

Pairing and Mobbing

When testers and developers work together in real-time, mindset differences become learning opportunities rather than conflicts.

A developer watching a tester explore their feature sees how testers think. A tester watching a developer debug an issue sees how developers think. Both perspectives expand.

Pairing on bug investigation is particularly valuable. The developer brings implementation knowledge. The tester brings investigation skills. Together they find root causes faster than either would alone.

Bug Report Conversations

Written bug reports lose nuance. Before a bug becomes a ticket, have a conversation.

“I found something weird. Let me show you.”

This simple practice transforms bug reporting from accusation to collaboration. The tester demonstrates the issue. The developer asks questions. Together they determine what happened, why it matters, and what to do about it.

Many “bugs” get resolved in these conversations — sometimes they’re not bugs, sometimes they’re quick fixes, sometimes they’re known issues. The conversation prevents unnecessary documentation and builds relationships.

Blameless Retrospectives

When bugs escape to production, the natural instinct is blame. Developers blame testers for missing it. Testers blame developers for creating it.

Blameless retrospectives redirect that energy. “How did this bug get through our process?” is a system question, not a people question.

These conversations surface process improvements that help both mindsets work better together. Maybe testers need earlier access to features. Maybe developers need better test environments. Maybe requirements need more clarity before implementation begins.

When Mindsets Should Flex

While each role has a default mindset, there are situations where flexing toward the other mindset improves outcomes.

Developers should flex toward testing mindset when:

Writing unit tests. Pure construction mindset writes tests that verify the code does what the code does. Testing mindset writes tests that verify the code does what users need.

Reviewing their own code. Construction mindset is proud of what was built. Testing mindset asks what could break.

Discussing bug reports. Construction mindset gets defensive. Testing mindset gets curious.

Planning implementation. Construction mindset asks how to build it. Testing mindset asks what could go wrong during building.

Testers should flex toward development mindset when:

Writing bug reports. Pure testing mindset documents problems. Development mindset helps solve them.

Prioritizing issues. Testing mindset wants everything fixed. Development mindset understands tradeoffs and constraints.

Discussing implementation approaches. Testing mindset focuses on what could break. Development mindset appreciates what’s being built.

Automating tests. Testing mindset focuses on what to test. Development mindset figures out how to build reliable automation.

The ability to flex is what separates good practitioners from great ones. It doesn’t mean abandoning your default — it means expanding your range.

The Organizational Dimension

Mindset differences don’t just exist between individuals. They exist between teams and departments.

Development organizations optimize for construction: features shipped, velocity maintained, deadlines met. Testing organizations optimize for evaluation: bugs found, risks identified, confidence established.

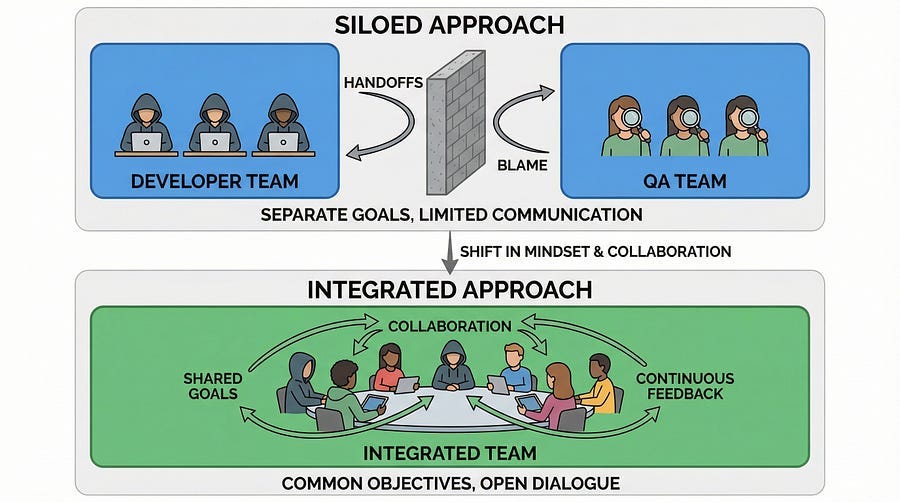

When these organizations operate in silos, their optimizations conflict. Development pushes for faster releases. Testing pushes for more thorough evaluation. Each sees the other as impediment rather than partner.

Modern organizations address this by breaking silos. Testers embedded in development teams rather than separate departments. Shared quality goals rather than competing metrics. Combined ownership of outcomes rather than handoffs and blame.

The organizational structure either amplifies mindset conflicts or creates conditions for mindset collaboration. If you’re in a siloed organization, advocating for structural change might be more important than improving individual relationships.

Building Your Cross-Mindset Fluency

Whether you’re a developer or tester, building fluency in the other mindset makes you more effective.

If you’re a developer:

Spend time with testers. Watch how they explore software. Ask why they investigate certain areas. Their approach will reveal blind spots in your thinking.

Read your own bug reports. Look for patterns. What types of issues do testers repeatedly find in your code? Those patterns reveal where your construction mindset has blind spots.

Write tests before code occasionally. Test-driven development forces you into evaluation mode before construction mode. Even if you don’t practice it religiously, the experience expands your thinking.

Attempt exploratory testing on your own features. Before declaring something done, spend ten minutes trying to break it. You’ll catch some issues and develop appreciation for what testers do.

If you’re a tester:

Spend time with developers. Watch how they build features. Ask why they make certain implementation decisions. Their approach will reveal constraints you might not appreciate.

Learn to read code. You don’t need to write production code, but understanding how software is built helps you test it more effectively and report bugs more usefully.

Build something small. A simple automation script, a basic application, anything that requires construction. The experience develops appreciation for how hard building is.

Pair on bug fixes. When a developer fixes your bug, watch how they do it. Understanding the fix deepens your understanding of the problem and helps you find similar issues elsewhere.

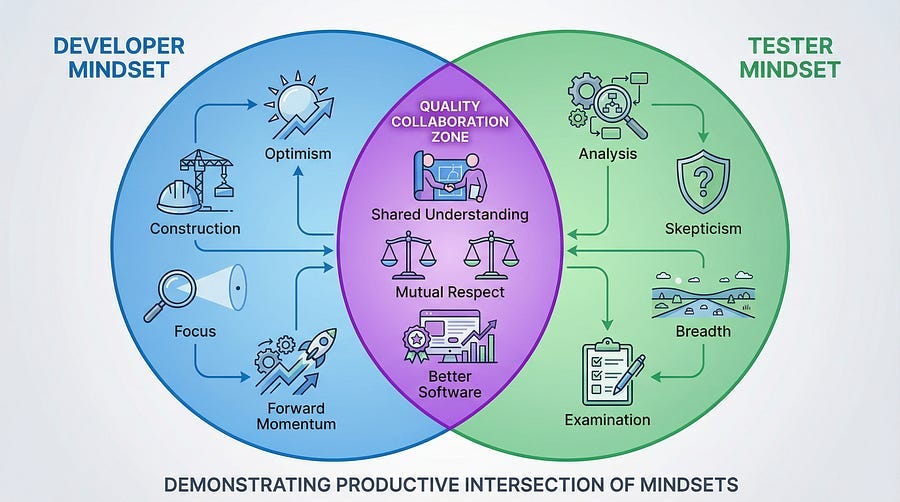

The Quality Mindset: Integration of Both

Ultimately, both mindsets serve the same goal: quality software that meets user needs.

The development mindset contributes by building software that works.

The testing mindset contributes by verifying software works and finding where it doesn’t.

Neither alone is sufficient. Construction without evaluation produces software that might work. Evaluation without construction produces nothing at all.

The mature practitioner — whether developer or tester — develops what might be called a quality mindset: the integration of both perspectives in service of shared outcomes.

This quality mindset asks both “how do we make this work?” and “how might this fail?”

It takes pride in construction while maintaining skepticism about whether construction succeeded.

It finds problems while appreciating the difficulty of solving them.

It moves forward while pausing to verify direction.

This integration is what great teams achieve together. Developers who think about testing. Testers who appreciate development. Shared commitment to building software that truly works.

Your Reflection Exercise

Take a moment to examine your own mindset patterns.

If you’re a developer:

When did you last find a bug in your own code before anyone else saw it?

How do you react when testers find issues in your work?

What testing activities, if any, do you perform before calling code complete?

Do you see testers as partners or obstacles?

If you’re a tester:

When did you last help a developer understand why a bug might be occurring?

How do you react when developers push back on your bug reports?

What do you understand about how the systems you test are built?

Do you see developers as partners or as people who create problems for you to find?

For everyone:

Which mindset is your default? Can you flex toward the other when needed?

What’s one practice you could adopt to build fluency in the other mindset?

How would your working relationships change if you better understood the other perspective?

Complementary, Not Competing

The testing mindset and development mindset aren’t in competition. They’re dance partners — different moves that combine into something neither could achieve alone.

Software that only gets built without rigorous evaluation is software waiting to fail in production.

Software that only gets evaluated without being built is software that doesn’t exist.

Quality emerges from the collaboration between these perspectives. Not from one mindset winning over the other, but from both contributing their strengths while respecting the other’s value.

The developer who appreciates testing becomes a better developer.

The tester who appreciates development becomes a better tester.

The team that integrates both mindsets builds better software than any individual could.

In our next article, we’ll explore Building Your Testing Career Path — mapping the journey from junior tester to test architect and beyond. We’ll examine the different trajectories available, the skills each level demands, and how to move intentionally through your career rather than hoping the next opportunity finds you.

Remember: Different mindsets aren’t obstacles to overcome. They’re perspectives to integrate.