Introduction to Manual Testing

When human judgment is irreplaceable

Everyone’s talking about automation. AI-generated test cases. Self-healing scripts. Codeless testing platforms that promise to eliminate manual work entirely.

And yet.

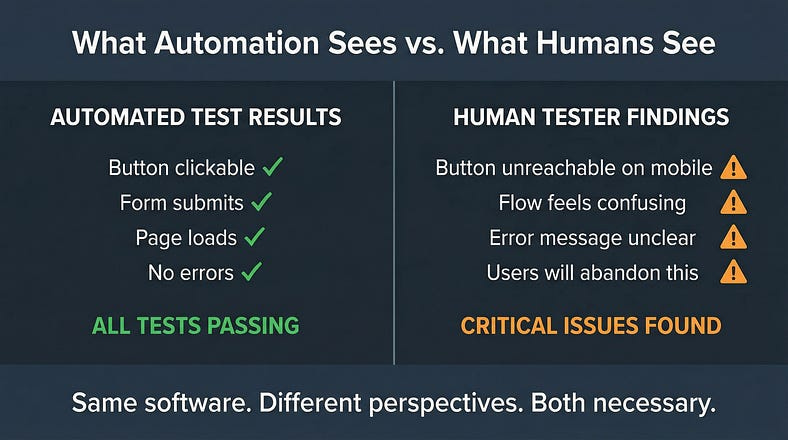

The login button works perfectly in automated tests but is positioned where users’ thumbs can’t reach it on mobile. The checkout flow passes every scripted scenario but feels so clunky that customers abandon their carts. The error messages are technically accurate but so confusing that users call support instead of fixing the problem themselves.

Automation didn’t catch any of this. A human tester would have caught all of it.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth the automation evangelists don’t want to admit: some things require human judgment. Not as a temporary limitation until technology catches up, but as a fundamental reality of what testing actually is.

Manual testing isn’t the absence of automation. It’s the presence of human intelligence applied directly to the problem of software quality. And in a world racing toward automation, understanding when and how to apply human judgment is more valuable than ever.

Today we’re exploring manual testing — not as a legacy practice to be eliminated, but as a sophisticated discipline that remains essential even in the most automated environments.

What Manual Testing Actually Is

Let’s start with a clear definition, because “manual testing” is often misunderstood.

Manual testing is the practice of a human tester directly interacting with software to evaluate its quality — without relying on automated scripts to perform the interactions or make the judgments.

Notice what that definition includes: human interaction, direct evaluation, and human judgment. The tester isn’t just clicking buttons — they’re thinking about what they’re experiencing, interpreting what they observe, and making assessments about quality.

This is fundamentally different from automated testing, where scripts perform predefined actions and compare results against predefined expectations. Automation asks: “Did the expected thing happen?” Manual testing asks: “Is this actually good?”

What manual testing is not:

It’s not “testing without tools.” Manual testers use plenty of tools — browsers, devices, debugging utilities, note-taking applications, screen recorders. The “manual” refers to human-driven interaction and judgment, not absence of technology.

It’s not “unskilled testing.” Effective manual testing requires deep skills in observation, analysis, critical thinking, and domain knowledge. The low barrier to entry doesn’t mean the ceiling is low.

It’s not “the thing we do until we automate.” Some testing should never be automated because automation would miss the point entirely. Manual testing isn’t a waystation — it’s a destination.

It’s not “slow and expensive testing.” Thoughtful manual testing often finds critical issues faster than the time required to write automated tests. The economics depend on context, not on some universal hierarchy where automation is always better.

The Irreplaceable Human Elements

Why can’t we just automate everything? Because certain aspects of quality evaluation require capabilities that machines don’t have — and may never have.

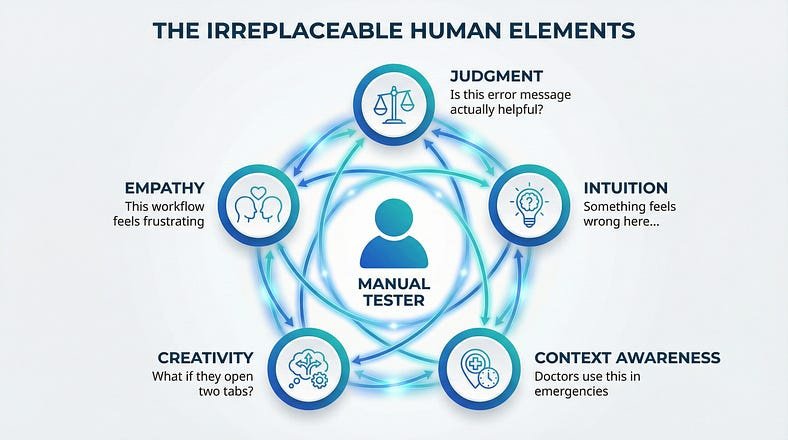

Judgment

Machines compare actual results to expected results. Humans judge whether those results are actually good.

An automated test can verify that an error message appears. It cannot judge whether that error message is helpful, clear, appropriately toned, and likely to guide the user toward a solution. That requires understanding human communication, emotional context, and user psychology.

A human tester looks at an error message that says “Error 5012: Transaction failed due to upstream service timeout” and immediately recognizes that a real user would have no idea what this means or what to do about it.

Judgment applies to everything: Is this layout intuitive? Is this response fast enough? Is this workflow reasonable? Is this feature actually solving the problem it claims to solve? These questions don’t have binary answers that automation can check.

Intuition

Experienced testers develop a sense for where bugs hide. They notice when something “feels off” before they can articulate why. They follow hunches that lead to unexpected discoveries.

This intuition comes from pattern recognition built over thousands of hours of testing. The tester has seen similar implementations fail in similar ways. They’ve developed mental models of how software tends to break.

Automation follows predefined paths. Human intuition explores undefined paths that turn out to matter.

I once watched a senior tester pause on a perfectly functional screen and say, “Something’s wrong here.” She couldn’t explain it immediately. After investigation, she discovered that the data being displayed was subtly incorrect — pulled from a cached response instead of current data. The screen worked perfectly. The test cases all passed. But something felt wrong to a human who knew the domain.

Context Awareness

Humans understand context in ways machines cannot.

A tester knows that this application is used by doctors in emergency situations, so response times that would be fine for casual browsing are unacceptable here. A tester knows that these users are elderly and may struggle with small text. A tester knows that this feature will launch during a holiday period when support staff is minimal.

This context shapes what “quality” means. The same software might be excellent in one context and terrible in another. Humans navigate context fluidly. Automation operates context-blind.

Creativity

Finding bugs often requires creative thinking — trying unexpected combinations, imagining unusual user behaviors, asking “what if” questions that nobody thought to include in requirements.

What if a user opens the same screen in two browser tabs? What if they’re copying and pasting from a PDF with hidden characters? What if they walk away mid-transaction and come back an hour later? What if they’re using a screen reader and a keyboard simultaneously?

Creative exploration surfaces issues that systematic automation never considers because nobody thought to automate those scenarios. The scenarios only became obvious after a human discovered them.

Empathy

Perhaps most importantly, human testers can empathize with users in ways that scripts cannot.

They can feel the frustration of a confusing workflow. They can experience the anxiety of wondering whether a payment went through. They can sense when an interface feels hostile or welcoming, trustworthy or suspicious.

This emotional dimension of quality is invisible to automation but deeply important to actual users.

When Manual Testing Is Essential

Manual testing isn’t always the right choice — but in certain situations, it’s the only choice that makes sense.

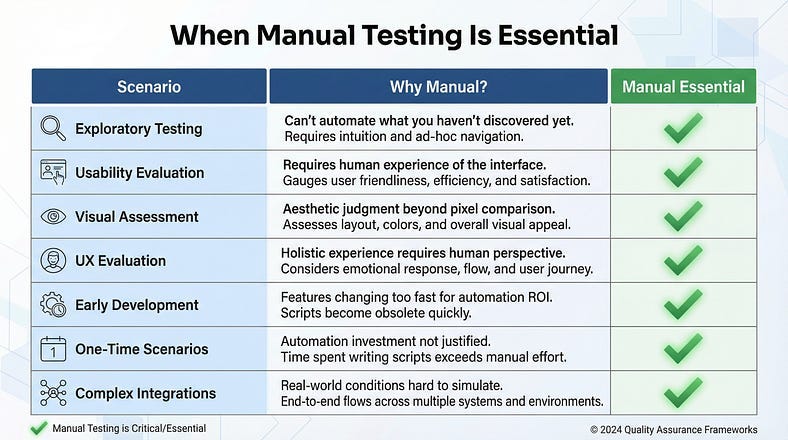

Exploratory Testing

When you’re investigating a new feature without predefined test cases, manual testing is the only option. You’re learning about the software as you test it, adapting your approach based on what you discover.

Exploratory testing is inherently human — it requires curiosity, judgment, and real-time decision-making about where to investigate next. You can’t automate exploration because you don’t know where you’re going until you get there.

Usability Evaluation

Is this software actually usable? Does it make sense to humans? Is it pleasant or frustrating to use?

These questions require a human to experience the software as a user would experience it. Automation can verify that buttons are clickable; it cannot evaluate whether users will understand what clicking those buttons will do.

Usability testing often reveals that technically correct software is practically unusable. The feature works perfectly but nobody can figure out how to access it.

Visual and Aesthetic Assessment

Does this look right? Is the design consistent? Do the colors convey the right mood? Is the spacing visually balanced?

Visual assessment requires human aesthetic judgment. Automated visual testing can compare screenshots against baselines, but it cannot judge whether a new design is actually better than the old one.

A tester notices that the new color scheme makes the “Delete” button too subtle — users might miss it when they need it or click it accidentally because it doesn’t stand out as dangerous. This is aesthetic judgment with functional implications.

User Experience Evaluation

Beyond usability, the overall experience — how the software makes users feel, whether the journey is satisfying, whether users accomplish their goals with confidence.

A tester experiences the end-to-end flow of signing up for an account, completing their first task, and returning the next day. They notice that the onboarding feels patronizing, the first task has too many steps, and returning users are forced through unnecessary confirmations.

This holistic experience evaluation requires human judgment about human experience.

Early Development Stages

When features are in flux, writing automated tests is wasteful — they’ll need constant updating as the feature changes. Manual testing provides rapid feedback without the overhead of test maintenance.

A tester can evaluate a rough prototype and provide meaningful feedback in minutes. That same tester writing automated tests for an unstable feature will spend days maintaining scripts that are obsolete by the time they’re finished.

One-Time or Rare Scenarios

Some testing only happens once or rarely — initial setup validation, migration testing, seasonal feature activation. The investment in automation isn’t justified when the test will run once or twice.

Manual testing is efficient for one-off validation. Automation investment makes sense for tests that run repeatedly.

Complex Integration Points

When testing involves complex external systems, unusual configurations, or environments that are difficult to automate, manual testing may be the practical choice.

A tester can manually verify integration with a third-party system that has no test environment. They can test on a physical device with specific characteristics. They can validate behavior that depends on real-world conditions.

The Core Manual Testing Techniques

Manual testing isn’t random clicking. It’s a disciplined practice with specific techniques that skilled testers apply deliberately.

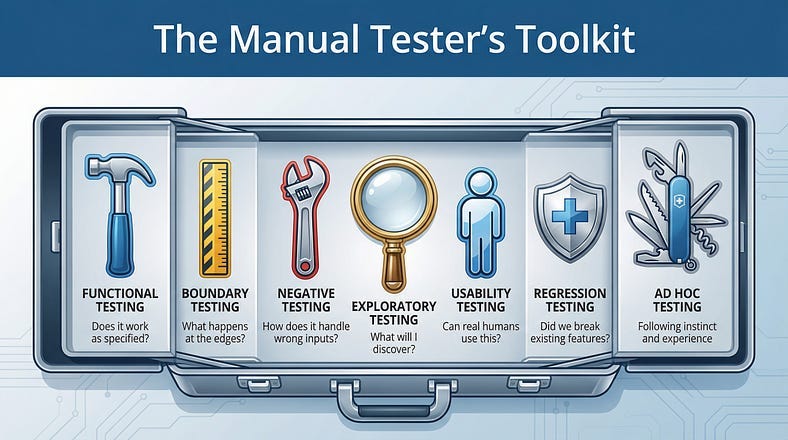

Functional Testing

Verifying that the software does what it’s supposed to do. Features work according to requirements. Inputs produce expected outputs. Business rules are correctly implemented.

A tester systematically works through the functionality: Can I create a new account? Can I log in with those credentials? Can I update my profile? Can I reset my password? Each capability is verified through direct interaction.

This is the foundation of manual testing — ensuring that the software actually works.

Boundary Testing

Exploring the edges of valid input ranges. What happens at the minimum? The maximum? Just below minimum? Just above maximum?

If a field accepts 1–100, a manual tester enters 1, 100, 0, 101, and sees what happens. They enter negative numbers. They enter decimals when integers are expected. They push the boundaries to see where the software breaks.

Boundaries are where bugs hide. Developers often get the “normal” cases right but mishandle the edges.

Negative Testing

Deliberately doing things wrong to verify the software handles errors gracefully. Invalid inputs. Missing required fields. Operations in the wrong order. Actions by unauthorized users.

What happens when I submit an empty form? What happens when I enter letters in a phone number field? What happens when I try to access a page I don’t have permission to view?

Good software fails gracefully. Manual testers verify that it does by trying to break it.

Exploratory Testing

Unscripted investigation driven by curiosity and learning. The tester interacts with the software, observes behavior, generates questions, and follows interesting paths.

This isn’t random — it’s strategic exploration guided by experience and intuition. The tester has a mission (learn about this feature) but not a script (click these buttons in this order).

Exploratory testing often finds bugs that scripted testing misses because it goes where scripts don’t.

Usability Testing

Evaluating the software from the user’s perspective. Is it intuitive? Is the workflow logical? Are labels clear? Can users accomplish their goals without confusion?

The tester approaches the software as a user would — sometimes literally pretending to be a specific type of user. They notice confusion, frustration, and unnecessary friction.

Usability issues often aren’t “bugs” in the traditional sense — the software works correctly but fails users anyway.

Regression Testing

Verifying that existing functionality still works after changes. New features shouldn’t break old ones. Bug fixes shouldn’t introduce new bugs. Updates shouldn’t cause regressions.

Manual regression testing focuses on areas likely to be affected by changes and areas where regressions would be most damaging. While automation often handles routine regression, manual testing catches the subtle regressions that automated tests miss.

Ad Hoc Testing

Informal testing without documentation or formal process. The tester interacts with the software based on instinct and experience.

Ad hoc testing sounds unstructured — and it is — but that’s the point. It’s the testing equivalent of jazz improvisation. Experienced testers apply their skills without the constraints of process.

This often happens after formal testing is “complete.” A tester continues poking at the software and discovers issues that formal approaches missed.

The Manual Testing Process

While manual testing is more flexible than automated testing, it still benefits from a structured approach.

Understanding Before Testing

Before touching the software, understand what you’re testing and why.

Review requirements, user stories, or specifications. Understand the intended users and their goals. Learn about the technical architecture if relevant. Identify areas of risk and complexity.

This preparation shapes your testing approach. You’ll test differently based on what you learn — focusing more attention on high-risk areas, adjusting your perspective based on who the users are.

Planning Your Approach

Even exploratory testing benefits from planning. What areas will you focus on? What types of testing will you apply? How much time will you allocate?

Planning doesn’t mean scripting every action. It means being intentional about your approach rather than randomly clicking. You might decide: “I’ll spend an hour exploring the checkout flow, focusing on edge cases and error handling.”

Executing with Attention

During testing, you’re not just clicking — you’re observing, analyzing, and thinking.

Notice everything. Response times. Visual glitches. Unexpected behaviors. Things that work but feel wrong. Questions that arise. Ideas for further investigation.

Take notes continuously. Your observations are valuable even when they don’t result in bug reports. Patterns emerge from accumulated observations.

Documenting Findings

When you find issues, document them clearly and completely.

A good bug report includes: what you did, what you expected, what actually happened, and evidence (screenshots, logs, video). It also includes your assessment of severity and impact.

But documentation goes beyond bugs. Observations about usability, questions about requirements, risks you’ve identified, and suggestions for improvement — all valuable outputs from manual testing.

Reflecting and Adjusting

After testing sessions, reflect on what you learned. What areas need more attention? What new questions arose? How should you adjust your approach?

Manual testing is iterative. Each session informs the next. You build a deeper understanding of the software over time, which makes your future testing more effective.

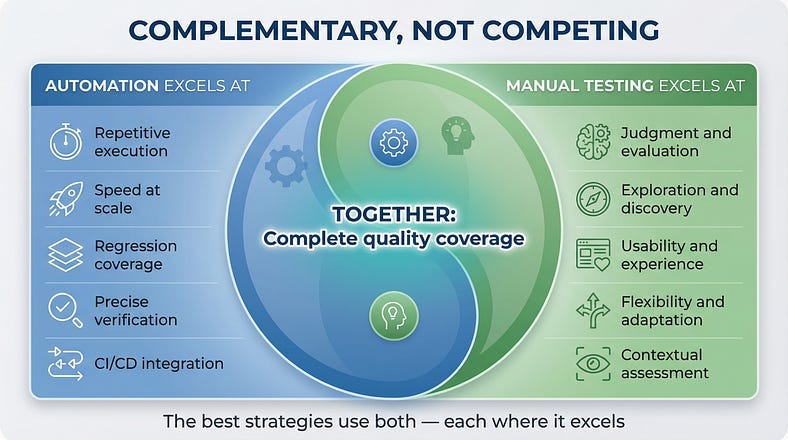

Manual vs. Automated: Complementary, Not Competing

Let’s be clear: this isn’t manual versus automated. The best testing strategies use both, applying each where it excels.

Automation excels at:

Repetitive execution — running the same tests hundreds of times without fatigue or variation.

Speed at scale — executing thousands of test cases faster than humans ever could.

Regression coverage — continuously verifying that existing functionality still works.

Precise verification — checking exact values, exact timing, exact behavior against exact expectations.

CI/CD integration — providing immediate feedback on every code change.

Manual testing excels at:

Judgment and evaluation — determining whether something is actually good, not just technically correct.

Exploration and discovery — finding issues that nobody thought to write tests for.

Usability and experience — assessing quality from the human perspective.

Flexibility and adaptation — responding to unexpected discoveries in real time.

Contextual assessment — evaluating quality given specific user needs and situations.

The smart approach uses both:

Automate the repetitive, precise, stable verification work. Apply manual testing for exploration, judgment, and human-centered evaluation. Let each approach do what it does best.

The ratio varies by context. A mature product with stable features might be 80% automated, 20% manual. A new product with evolving features might be the inverse. The right balance depends on your specific situation.

Common Manual Testing Pitfalls

Manual testing can fail just like any other practice. Here’s what to avoid.

Undisciplined Wandering

Exploratory testing is strategic exploration. It’s not aimless clicking without purpose or plan.

Undisciplined testing wastes time and misses issues. Without intention, testers often stay in comfortable areas and avoid challenging ones. They duplicate effort without realizing it. They fail to investigate findings deeply enough.

The fix: Always have a mission. Know what you’re investigating and why. Take notes to maintain awareness of where you’ve been.

Happy Path Fixation

It’s easy to keep testing things that work. The happy path is comfortable. Everything succeeds. It feels productive.

But quality problems hide in the unhappy paths — error handling, edge cases, unexpected inputs, unusual sequences. Testers who avoid discomfort find fewer bugs.

The fix: Deliberately test the uncomfortable paths. Try to break things. Enter bad data. Take wrong turns. The bugs are where users struggle, not where they succeed.

Assumption Blindness

Testers often assume they know how something works and test based on those assumptions — missing bugs that violate the assumptions.

You assume the date field expects MM/DD/YYYY. You assume the form validates on submit. You assume logged-in users see different content. When assumptions are wrong, bugs hide behind them.

The fix: Question your assumptions explicitly. Try things that should be impossible. Test what happens, not what you think should happen.

Inadequate Documentation

Finding a bug but failing to document it well is almost as bad as not finding it. Unclear bug reports get deprioritized or closed as “cannot reproduce.”

Testers sometimes think their job is finding bugs. Actually, the job is communicating about quality in ways that lead to improvement. Documentation is essential.

The fix: Treat bug reports as important deliverables. Invest time in clarity and completeness. Include evidence. Explain impact.

Testing in Isolation

Manual testers sometimes operate independently, missing opportunities to leverage what others know.

Developers know where the code is fragile. Product managers know which features matter most. Users know where they struggle. This knowledge should inform testing.

The fix: Collaborate. Ask developers where they’re worried about bugs. Review customer complaints. Align testing with what actually matters.

Confirmation Bias

Testers sometimes unconsciously test in ways that confirm the software works rather than genuinely trying to find problems.

This often happens when testers feel pressure to approve releases. They run through tests quickly, accept marginal results, and don’t dig into suspicions.

The fix: Adopt a genuinely skeptical mindset. Your job is to find the truth, not to confirm that everything is fine.

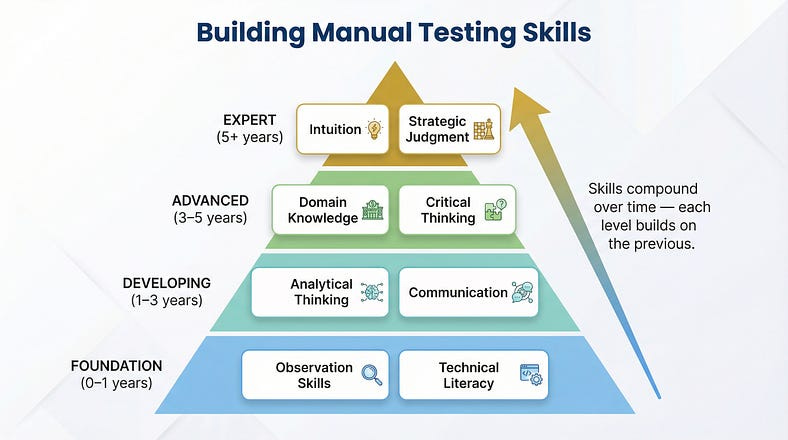

Building Manual Testing Skills

Manual testing looks simple from the outside. In practice, it requires skills that develop over years.

Observation Skills

Noticing what’s happening — not just the obvious, but the subtle. Response time changes. Visual inconsistencies. Behavior that’s slightly different from last time.

Build this skill by practicing deliberate observation. After testing a screen, close your eyes and describe everything you saw. What did you miss? Train yourself to see more.

Analytical Thinking

Understanding why something is happening. Connecting symptoms to causes. Recognizing patterns across multiple observations.

Build this skill by investigating bugs deeply, not just reporting symptoms. Practice root cause analysis. Ask “why” repeatedly until you understand what’s actually happening.

Domain Knowledge

Understanding the business context that makes software meaningful. Knowing what users need, what the market expects, what regulations require.

Build this skill by studying your domain. Talk to users. Read industry publications. Understand the problems the software solves, not just the features it provides.

Technical Literacy

Understanding enough about how software works to test it effectively. Knowing how databases, APIs, browsers, and networks behave.

Build this skill through deliberate learning. Take courses. Read documentation. Ask developers to explain how things work. You don’t need to code, but you need to understand.

Communication

Translating observations into clear, actionable information. Writing bug reports that get fixed. Explaining quality status to stakeholders. Influencing without authority.

Build this skill by treating every communication as practice. Review your bug reports after issues are fixed — did developers understand? Get feedback on your status reports. Learn from communication that works.

Critical Thinking

Questioning assumptions. Evaluating evidence. Resisting cognitive biases. Distinguishing between what you observed and what you concluded.

Build this skill by practicing skepticism — of the software, of requirements, of your own conclusions. Seek disconfirming evidence. Ask “how might I be wrong?”

Manual Testing in the Age of AI

Here’s the irony: as AI gets better at automation, manual testing becomes more valuable, not less.

AI Amplifies, Humans Judge

AI can generate test cases, suggest areas of risk, and even execute exploratory sequences. But AI cannot judge whether the software is actually good. It cannot feel the user experience. It cannot apply contextual understanding that wasn’t in its training data.

The future isn’t AI replacing manual testers. It’s AI amplifying manual testers — handling the routine work so humans can focus on judgment, exploration, and experience evaluation.

Testing AI Systems

AI-powered features require human testing more than traditional features do.

AI outputs are probabilistic, not deterministic. The same input might produce different outputs. “Correct” is often subjective. Edge cases are effectively infinite.

How do you verify that an AI recommendation is good? That a generated summary is accurate? That a chatbot response is appropriate? These require human judgment — there’s no automated oracle.

As software becomes more AI-powered, manual testing of AI behavior becomes essential.

Human Skills, Augmented

The manual testing skills we discussed — observation, analysis, judgment, empathy — become more valuable when AI handles the mechanical work.

A tester who can leverage AI to generate initial test ideas, then apply human judgment to refine and execute them, is more effective than either AI or human alone.

The future belongs to testers who embrace AI as a tool while maintaining the human skills that AI cannot replicate.

Starting Your Manual Testing Practice

If you’re new to manual testing, here’s how to begin.

Start With Curiosity

Approach software with genuine curiosity. Wonder how it works. Ask what happens if you do unexpected things. Follow your questions wherever they lead.

Curiosity is the foundation of good testing. It drives exploration, motivates investigation, and sustains attention through long testing sessions.

Learn One System Deeply

Pick one application and learn it thoroughly. Understand its features, its users, its quirks. Test it repeatedly until you develop intuition about where bugs hide.

Deep knowledge of one system teaches you how to build knowledge of any system. The meta-skill transfers even when the specific knowledge doesn’t.

Practice Deliberate Observation

After each testing session, write down everything you observed — not just bugs, but behaviors, questions, suspicions. Train yourself to notice more.

Review your notes after time passes. What did you miss? What turned out to matter? What didn’t? This reflection builds observational skill.

Study Test Design

Learn formal techniques — equivalence partitioning, boundary analysis, decision tables, state transition testing. These give structure to exploration.

You don’t need to apply techniques rigidly, but understanding them expands your mental toolkit. You’ll recognize situations where specific techniques apply.

Find Mentors

Learn from experienced testers. Watch how they approach testing. Ask how they decide what to test. Study their bug reports.

Testing skill is largely tacit — learned through observation and practice more than instruction. Mentors accelerate that learning.

Test Everything

Practice on everything. Test websites you use daily. Test apps on your phone. Test physical products and processes. Testing is a way of seeing the world.

The more you practice testing thinking, the more natural it becomes. Eventually, you can’t stop seeing quality issues everywhere.

Your First Manual Testing Exercise

Theory is useful. Practice is essential. Here’s an exercise to start building your skills.

Pick an application you use regularly. Not something you test for work — something you use personally. A banking app. A social media platform. An e-commerce site.

Spend 30 minutes exploring with testing eyes. Don’t just use it — test it. Try edge cases. Enter unexpected inputs. Navigate in unusual sequences. Try to confuse it.

Document everything you observe. Not just bugs — behaviors, questions, usability issues, things that feel wrong even if you can’t articulate why.

Write up your three most interesting findings. For each: what you observed, what you expected, why it matters, and how you would communicate this to the development team.

Reflect on the experience. What was easy? What was difficult? What would you do differently next time? What questions do you still have?

This single exercise will teach you more about manual testing than reading another three articles. Do it today.

The Enduring Value of Human Testing

In a world obsessed with automation and AI, manual testing might seem like a relic. It’s not.

Manual testing is the application of human intelligence to the problem of software quality. It’s judgment, intuition, creativity, and empathy directed at understanding whether software actually works for the humans who use it.

Automation handles the repetitive, the precise, the scalable. Manual testing handles the nuanced, the subjective, the contextual. Together, they provide complete quality coverage that neither achieves alone.

The testers who thrive in the coming years won’t be those who resist automation. They’ll be those who understand when human judgment is irreplaceable — and apply that judgment with skill, discipline, and purpose.

In our next article, we’ll explore Exploratory Testing Fundamentals — the art of learning and testing simultaneously. We’ll examine how skilled testers structure their exploration, adapt in real-time to discoveries, and uncover bugs that scripted approaches never find.

Remember: Automation asks “Did the expected thing happen?” Manual testing asks “Is this actually good?” Both questions matter. Both need answers.