Exploratory Testing Fundamentals

Structured learning and testing simultaneously

The test case said: “Enter a valid email address. Verify the form submits successfully.”

So the tester entered “test@example.com” and clicked submit. Green checkmark. Test passed. Move on.

Nobody ever tested what happens when you paste an email with invisible Unicode characters copied from a PDF. Nobody tested submitting the form while the network drops mid-request. Nobody tested what happens when you hit submit twice in rapid succession because the button didn’t gray out.

Three production bugs. Zero test cases written for them. Because you can’t write a test case for something you haven’t imagined yet.

This is the fundamental limitation of scripted testing: it can only verify what someone thought to check. The bugs that matter most — the ones that surprise you, embarrass you, cost you customers — are often the ones nobody thought to script.

Exploratory testing exists to find those bugs.

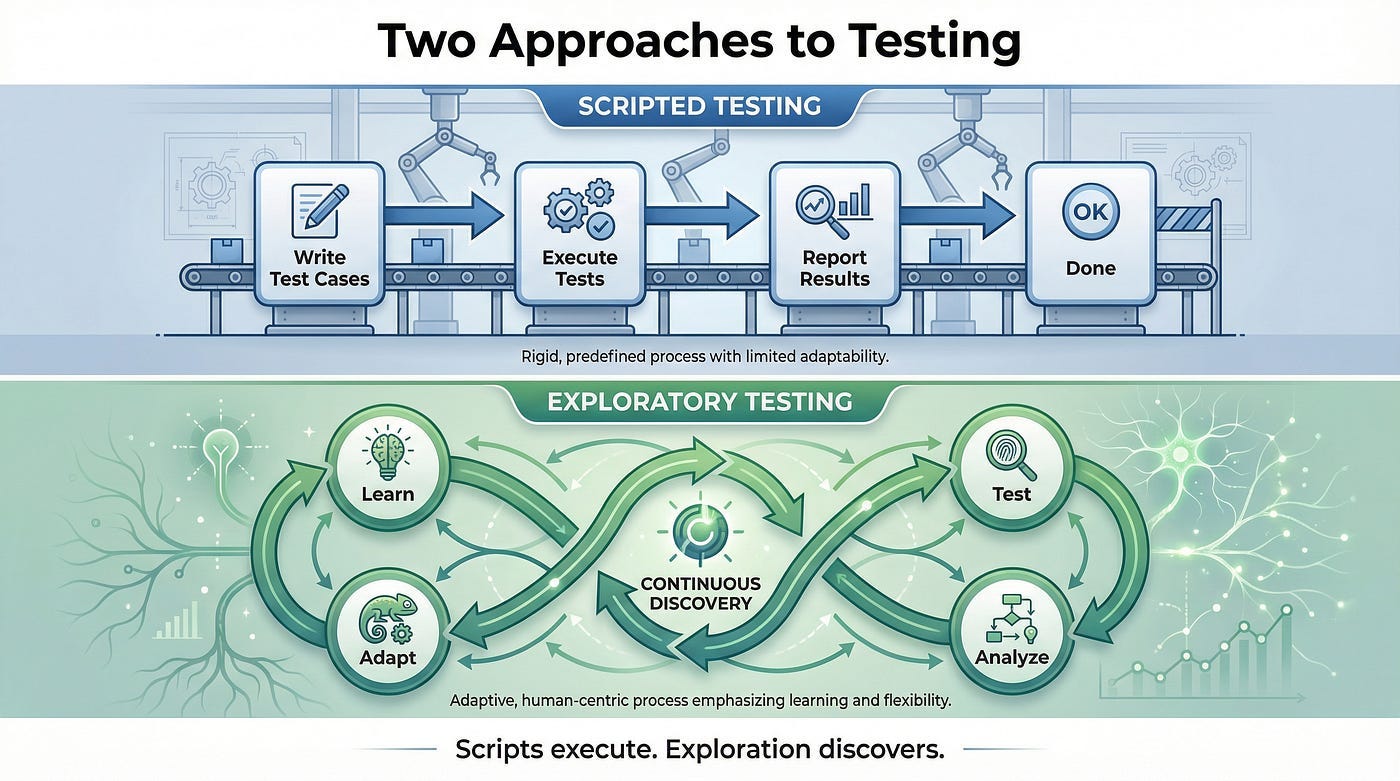

Yes, it’s testing without a rigid plan. That’s the point. Instead of following a predetermined script, you’re learning about the software as you test it — designing tests, executing them, and interpreting results simultaneously. What you discover shapes what you test next. The approach adapts in real-time to the reality of the software rather than the assumptions someone made before testing began.

But “no rigid plan” doesn’t mean “no structure.” The best exploratory testing is guided by charters, heuristics, and timeboxes that provide direction without constraining discovery.

Today we’re diving into exploratory testing fundamentals — what it actually is, why it consistently finds bugs that scripts miss, and how to practice it with discipline rather than chaos.

What Exploratory Testing Actually Is

Let’s start with a proper definition, because the term gets abused.

James Bach, who coined the term with Cem Kaner, defines exploratory testing as:

“Simultaneous learning, test design, test execution, and test result interpretation.”

Read that again. Four activities happening at the same time, not in sequence.

In scripted testing, these activities are separated. Someone writes test cases (design). Later, someone executes those test cases (execution). Then someone analyzes the results (interpretation). Learning might happen eventually, but it’s not integrated into the process.

In exploratory testing, these activities are interleaved continuously. You’re learning about the software as you test it. What you learn shapes what you test next. What you test reveals new things to learn. The cycle continues throughout the session.

This is not:

“Testing without preparation.” Exploratory testers prepare extensively — they just don’t script their exact actions in advance.

“Random clicking.” Exploratory testing is guided by strategy, heuristics, and objectives. It’s deliberate, not random.

“Testing without documentation.” Exploratory testers document their findings, their approach, and their learning. The documentation happens during and after testing, not before.

“The absence of test cases.” Exploratory testing generates test cases — it just generates them in real-time based on learning rather than in advance based on assumptions.

“Easy or unskilled testing.” Exploratory testing requires more skill than scripted testing, not less. It demands simultaneous thinking on multiple levels.

This is:

A disciplined approach where human intelligence is applied directly to the testing problem, adapting in real-time to discoveries.

A method that leverages human strengths — creativity, intuition, contextual understanding — rather than suppressing them behind scripts.

A way of testing that treats testers as intelligent investigators rather than human automation.

Why Exploratory Testing Finds More Bugs

Exploratory testing consistently finds bugs that scripted testing misses. This isn’t magic — it’s the natural result of how the approach works.

Scripts Test Assumptions

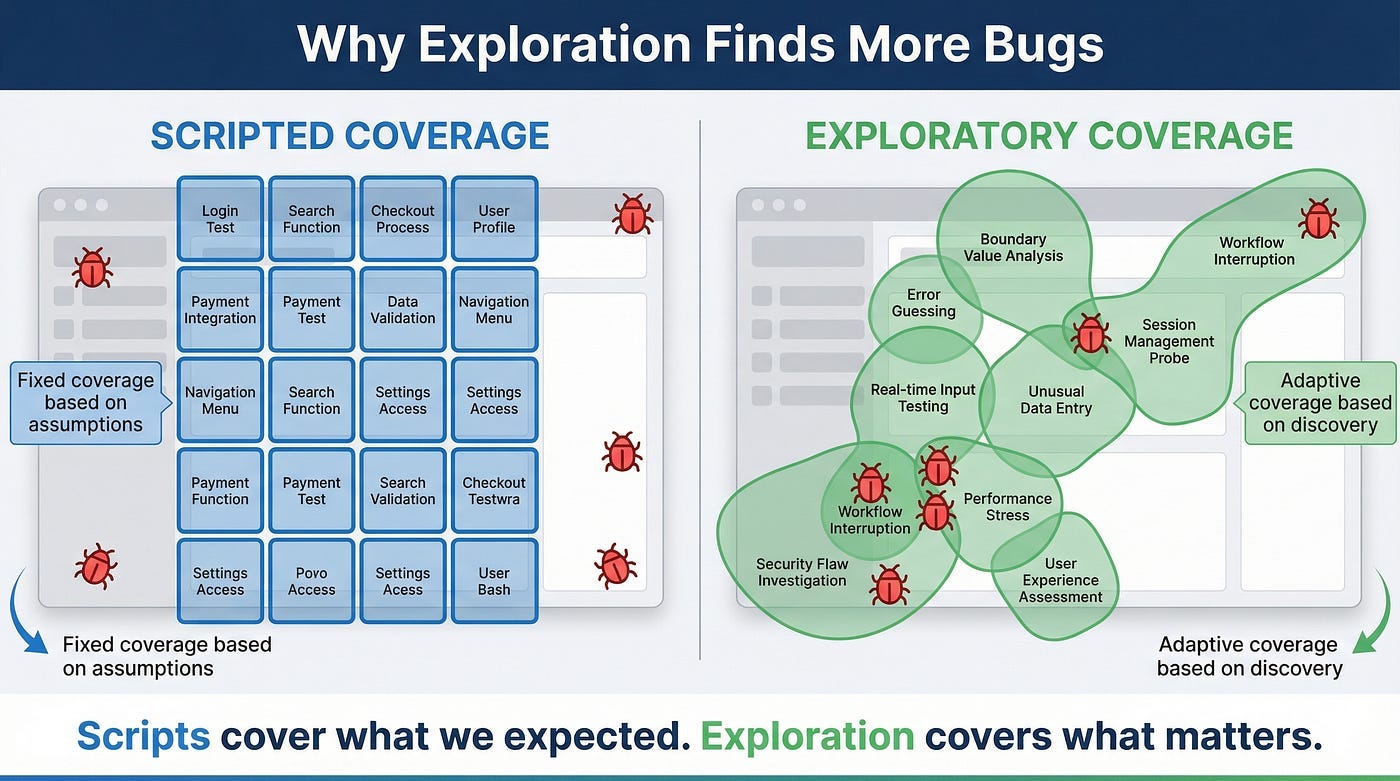

When you write a test case in advance, you’re encoding assumptions about how the software works and how users will use it.

But assumptions are often wrong. Requirements are incomplete. Users do unexpected things. The software behaves differently than anticipated. Edge cases aren’t obvious until you start interacting with the system.

Scripts test the world as we imagine it. Exploration tests the world as it actually is.

Real-Time Adaptation

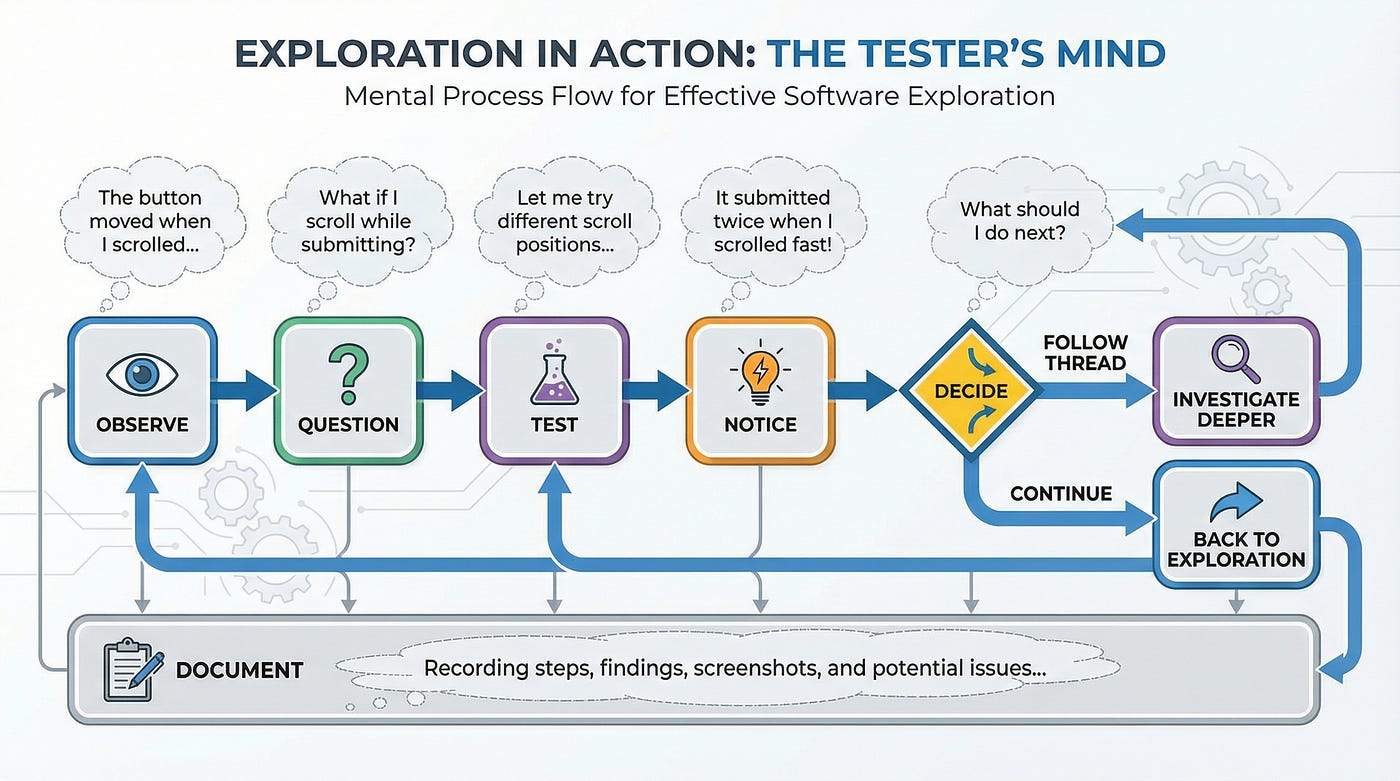

When an exploratory tester notices something unexpected, they can immediately investigate. They can follow the thread wherever it leads.

When a scripted tester notices something unexpected, they face a choice: stop to investigate (abandoning the script) or note it for later (potentially forgetting or deprioritizing it). The script is a constraint that limits responsiveness.

Bugs often reveal themselves through subtle signals — slightly slow response, unexpected behavior in one corner of the screen, data that doesn’t quite look right. Exploratory testers can pursue these signals immediately. Script followers often don’t.

Combinatorial Explosion

The number of possible test scenarios for any non-trivial feature is effectively infinite. Scripts can only cover a finite selection. That selection is chosen based on assumptions about what matters — assumptions that might be wrong.

Exploratory testing doesn’t try to cover everything. Instead, it uses human judgment to continuously select the most promising areas to investigate. As learning accumulates, those selections get smarter.

This intelligent adaptation is more likely to find important bugs than a predefined selection made before testing began.

Fresh Perspective

Scripted tests often become stale. The same tests run repeatedly, covering the same ground. Testers executing scripts stop really seeing the software — they’re just going through motions.

Exploratory testing demands engagement. You can’t explore on autopilot. This engaged attention notices things that rote execution misses.

Holistic Understanding

Exploratory testing builds a mental model of the entire system. This holistic understanding reveals inconsistencies, integration issues, and problems that span features.

Scripted testing often covers features in isolation. The tests verify individual behaviors but miss how those behaviors interact. Exploratory testers naturally cross feature boundaries because their investigation follows the software, not the test plan.

The Structure Within Exploration

Here’s where most people get exploratory testing wrong: they think “unscripted” means “unstructured.”

The best exploratory testing is highly structured. The structure just looks different from scripted testing.

Session-Based Testing

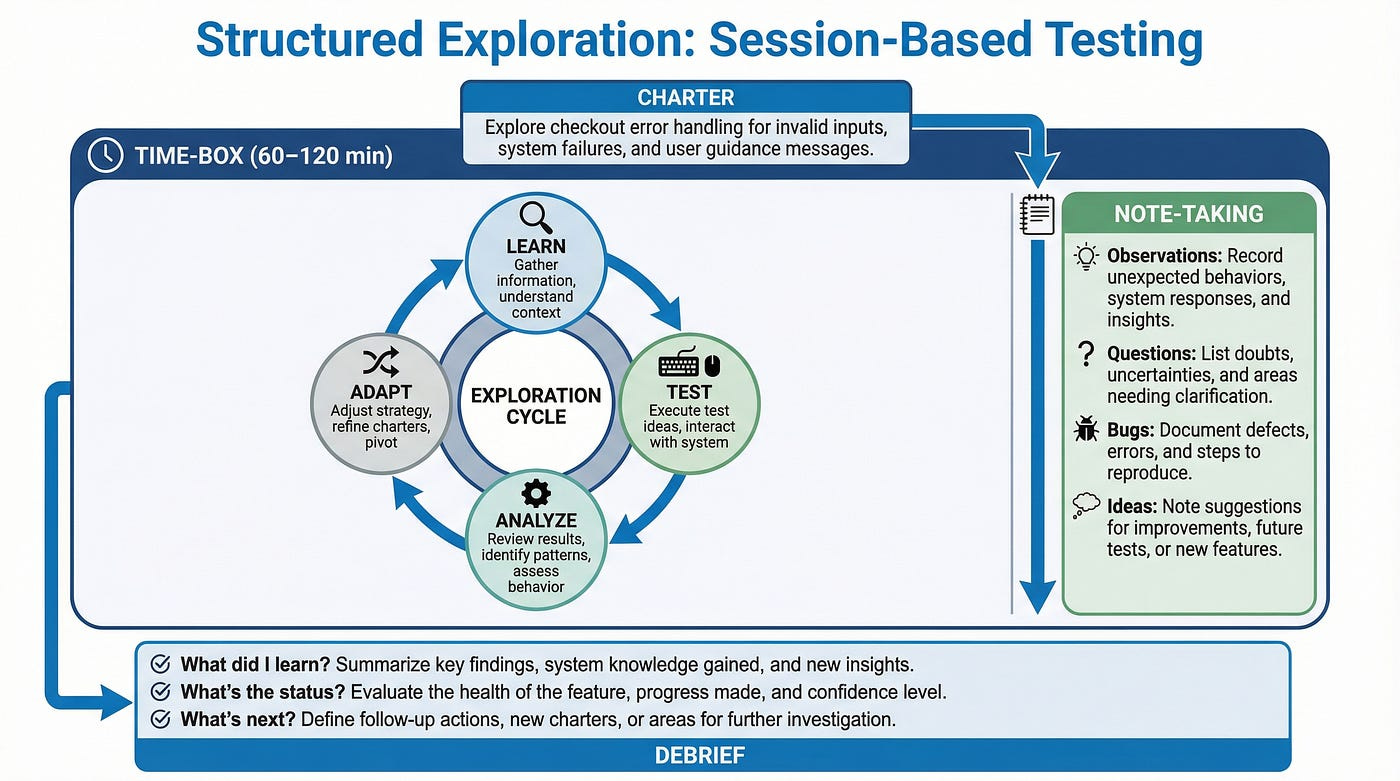

The most common structure for exploratory testing is the session — a focused block of time with a specific charter.

A session is typically 60–120 minutes of uninterrupted testing. It has a clear start and end. It’s focused on a specific mission. It produces documented results.

This structure provides accountability without constraining the testing itself. You know what each session was trying to accomplish and what it produced.

Charters

A charter is a mission statement for an exploration session. It answers: What are we investigating? Why does it matter? What areas are in scope?

Good charters provide direction without dictating actions:

“Explore the checkout flow with focus on error handling when payment fails.”

“Investigate how the application behaves when the user has extremely long text in profile fields.”

“Test the new search feature to understand its capabilities and limitations.”

Notice what these charters don’t include: specific steps, exact test cases, or predetermined pass/fail criteria. They provide direction while preserving freedom.

Time-Boxing

Exploratory testing benefits from time constraints. Without them, investigation can expand indefinitely. With them, testers must make strategic choices about where to focus.

Time-boxing also provides natural breakpoints for documentation, reflection, and planning. After each time box, you assess: What did I learn? What should I investigate next? Is this area worth more time?

Note-Taking

Exploratory testers take notes continuously — not to follow a script but to record what they’re doing, what they’re learning, and what they’re finding.

Good exploration notes include:

What you tested and how

What you observed (expected and unexpected)

Questions that arose

Ideas for future investigation

Bugs found with reproduction details

These notes serve multiple purposes: they support bug reports, they guide future sessions, and they provide evidence of what was tested.

Debriefing

After exploration sessions, testers debrief — either with themselves or with their team. What was discovered? What’s the quality status? What areas need more attention?

Debriefing transforms individual exploration into organizational learning. It surfaces findings, identifies patterns across sessions, and guides future testing strategy.

Planning Your Exploration

“No scripts” doesn’t mean “no preparation.” Effective exploratory testing requires thoughtful planning — just different planning than scripted testing requires.

Understanding the Mission

Before exploring, understand why you’re testing. What’s the goal? What does success look like?

Are you trying to find as many bugs as possible? Assess readiness for release? Understand a new feature? Verify a fix? Different missions lead to different exploration strategies.

A bug-hunting mission focuses on areas likely to contain defects. A release assessment mission covers critical functionality breadth. A learning mission prioritizes building understanding over finding problems.

Gathering Context

Collect information that will guide your exploration:

Requirements and specifications. What is the software supposed to do? What are the business rules? What are the stated constraints?

Architecture and design. How is it built? Where are the integration points? What technologies are involved?

Risk information. What areas are new or changed? What’s complex? What’s been problematic before? What would hurt most if it failed?

User information. Who uses this software? How do they use it? What are their goals and frustrations?

This context shapes where you explore and what you’re looking for.

Identifying Focus Areas

You can’t explore everything equally. Prioritize based on risk.

High-priority areas typically include:

New or recently changed functionality

Complex features with many interactions

Features that handle sensitive data or critical processes

Areas that have historically been buggy

Integration points with external systems

Features that many users rely on frequently

Lower-priority areas might include:

Stable functionality that hasn’t changed

Features with extensive automated coverage

Low-impact features used rarely

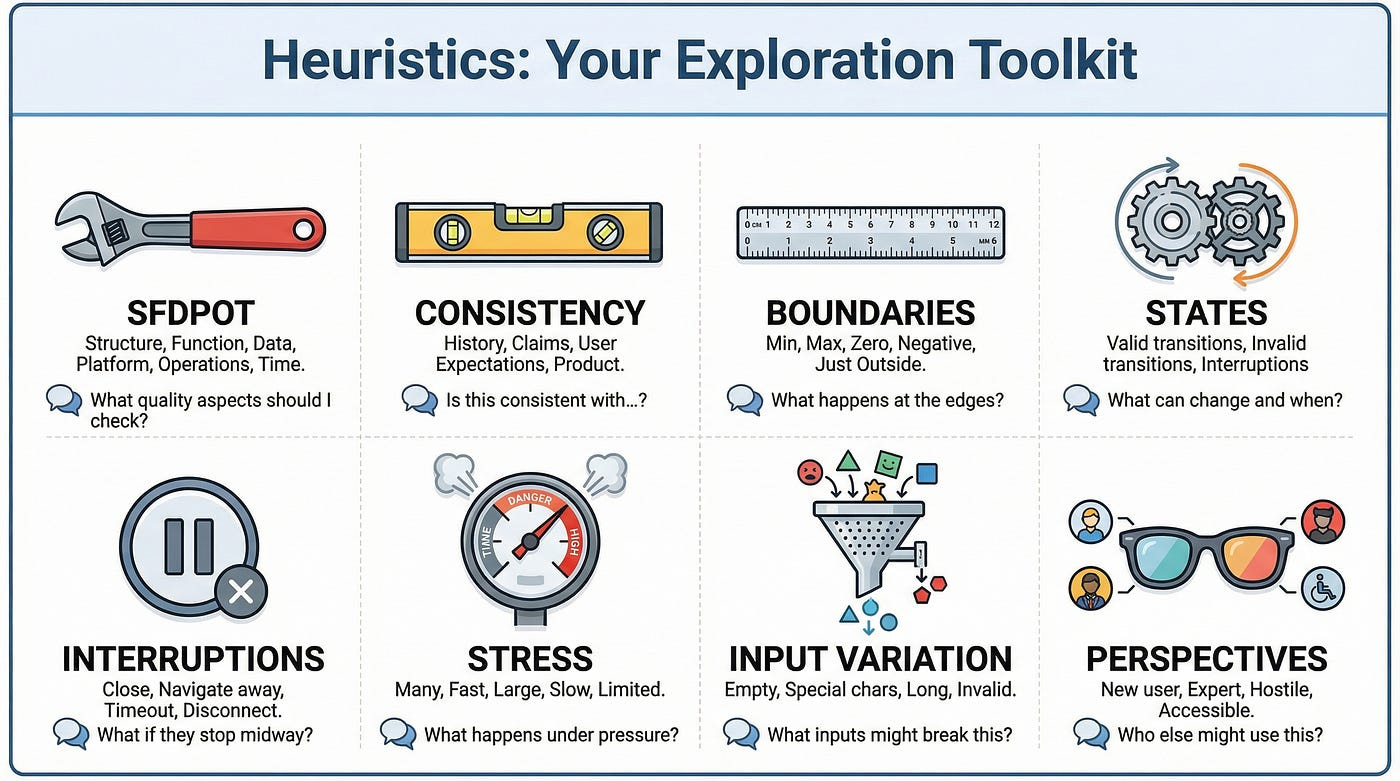

Choosing Heuristics

Heuristics are mental frameworks that guide exploration. They’re rules of thumb that suggest what to test.

Before a session, consider which heuristics might apply:

Input variations (boundary values, invalid data, empty inputs)

State transitions (what happens between states?)

Interruptions (what if the user stops mid-process?)

Configuration variations (different browsers, settings, permissions)

Stress conditions (slow network, many items, concurrent users)

Having heuristics in mind gives exploration direction without constraining it to predetermined steps.

Creating Initial Questions

Start with questions you want to answer:

Can a user complete the checkout with an expired credit card? What happens if the session times out during payment processing? How does the search handle special characters? Is the error messaging consistent across the application?

These questions provide starting points for exploration. You’ll generate more questions as you test.

During the Session: How to Explore

Now you’re in the session. The charter is set, the timer is running, and you’re face-to-face with the software. How do you actually explore?

Start With a Tour

Begin by getting oriented. Do a quick tour of the area you’re exploring. Understand the landscape before diving into details.

What are the main features? What are the entry and exit points? What data is involved? What states can the system be in?

This orientation prevents the common mistake of diving too deep into one area before understanding the whole.

Follow the “What If” Principle

Exploration is driven by questions. The most powerful question is “What if?”

What if I enter nothing? What if I enter too much? What if I go backward? What if I do this twice? What if I’m not logged in? What if the network is slow? What if I open two tabs?

Each “what if” generates a test. The answer generates more questions.

Vary Your Inputs

Don’t just test with “normal” data. Vary your inputs systematically:

Boundaries: Minimum, maximum, just below, just above. Invalid data: Wrong types, wrong formats, malicious content. Empty and null: Missing required fields, blank values. Special characters: Unicode, emojis, HTML, SQL fragments. Length extremes: Very short, very long. Real-world data: Actual content users would enter.

Input variation surfaces bugs that “happy path” data never triggers.

Change Your Perspective

Periodically shift how you’re thinking about the software:

New user perspective: What if I’ve never seen this before? Expert user perspective: What shortcuts would power users want? Hostile user perspective: How could someone abuse this? Accessibility perspective: Can users with disabilities use this? Support perspective: What questions will confused users ask?

Each perspective reveals different issues.

Notice Everything

Exploratory testing requires active observation. Don’t just watch for pass/fail — notice everything:

Response times (faster or slower than expected?)

Visual presentation (alignment, consistency, aesthetics)

Language and messaging (clear, helpful, appropriate?)

Behavior patterns (consistent with rest of application?)

Data handling (saved correctly, displayed correctly?)

Things that seem “not quite right” often lead to important bugs.

Follow Threads

When you notice something interesting, follow it. Don’t note it for later and continue with your plan — pursue it now while you’re in context.

Many important bugs are discovered by pulling on threads. The initial observation leads to an investigation, which leads to a deeper problem. If you don’t follow threads immediately, they often go cold.

Take Notes Continuously

Don’t rely on memory. Document as you go:

Steps you’re taking

Observations you’re making

Questions arising

Bugs found

Ideas for further investigation

These notes support later bug reports, inform future sessions, and provide evidence of your coverage.

Heuristics: Your Exploration Toolkit

Heuristics are mental tools that suggest what to test. They’re not prescriptive rules — they’re prompts that trigger ideas. Experienced exploratory testers carry dozens of heuristics that they apply intuitively.

Here are essential heuristics to add to your toolkit:

SFDPOT (San Francisco Depot)

A mnemonic for high-level quality aspects:

Structure: Is the product built correctly? Code, architecture, dependencies. Function: Do the features work as intended? Data: Is data handled correctly? Input, output, storage, retrieval. Platform: Does it work across environments? Browsers, devices, OS versions. Operations: Can it be deployed, maintained, and monitored? Time: How does time affect it? Timeouts, sessions, scheduling.

HICCUPPS (Consistency Heuristics)

Ways to identify inconsistencies that suggest bugs:

History: Is behavior consistent with past versions? Image: Is behavior consistent with the company brand? Comparable Products: Is behavior consistent with similar products? Claims: Is behavior consistent with documentation and specs? User Expectations: Is behavior consistent with what users expect? Product: Is behavior consistent within the product itself? Purpose: Is behavior consistent with the product’s purpose? Standards: Is behavior consistent with industry standards?

FEW HICCUPPS (Feeling)

Add emotional/experiential dimension:

Feeling: Does this feel right? Does it feel frustrating, confusing, or satisfying?

Sometimes your gut knows something is wrong before you can articulate why.

Boundary Testing Heuristic

At every input, consider:

Minimum valid value

Maximum valid value

Just below minimum

Just above maximum

Zero / empty / null

Negative (where applicable)

State Transition Heuristic

For any feature with states:

Test valid transitions between states

Test invalid transitions (should they be prevented?)

Test returning to previous states

Test remaining in current state

Test the effect of external events on state

Interruption Heuristic

Test what happens when processes are interrupted:

Close the browser mid-action

Navigate away and back

Let session timeout

Lose network connection

Have another user modify the same data

Stress Heuristic

Test under pressure:

Many items (thousands instead of dozens)

Fast actions (rapid clicking, quick navigation)

Large data (huge files, long text)

Slow network (throttled connection)

Limited resources (low memory, slow CPU)

Documenting Your Exploration

Documentation in exploratory testing serves different purposes than in scripted testing. You’re not documenting what to do — you’re documenting what you did, learned, and found.

Session Notes

During exploration, capture:

Coverage: What areas did you explore? What did you actually test?

Observations: What did you notice? Include both problems and normal behavior worth recording.

Questions: What questions arose? What remains uncertain?

Bugs: Issues found, with enough detail to reproduce.

Ideas: What should be investigated further? What deserves automation?

The Session Report

After each session, produce a brief report:

Charter: What was the mission?

Duration: How long did you actually spend?

Coverage: What did you explore? (List of areas, features, or scenarios)

Findings: What did you discover? (Bugs, observations, concerns)

Assessment: What’s your overall impression of quality in this area?

Next steps: What should happen next?

This report makes exploratory testing visible and accountable.

Bug Reports from Exploration

When you find bugs during exploration, document them thoroughly:

Title: Clear, specific summary of the issue.

Steps to reproduce: Exact actions to recreate the bug.

Expected result: What should have happened.

Actual result: What actually happened.

Evidence: Screenshots, videos, logs.

Severity assessment: How bad is this?

Context: What were you exploring when you found this? What led you here?

The context is especially valuable — it helps developers understand not just the bug but the conditions around it.

Traceability

How do you show what exploratory testing covered?

Session logs: Document what was tested in each session.

Mind maps: Visual representation of areas explored.

Coverage notes: List of features, scenarios, or risk areas addressed.

Heuristic tracking: Which heuristics were applied where.

This documentation provides evidence that exploration was systematic, not random.

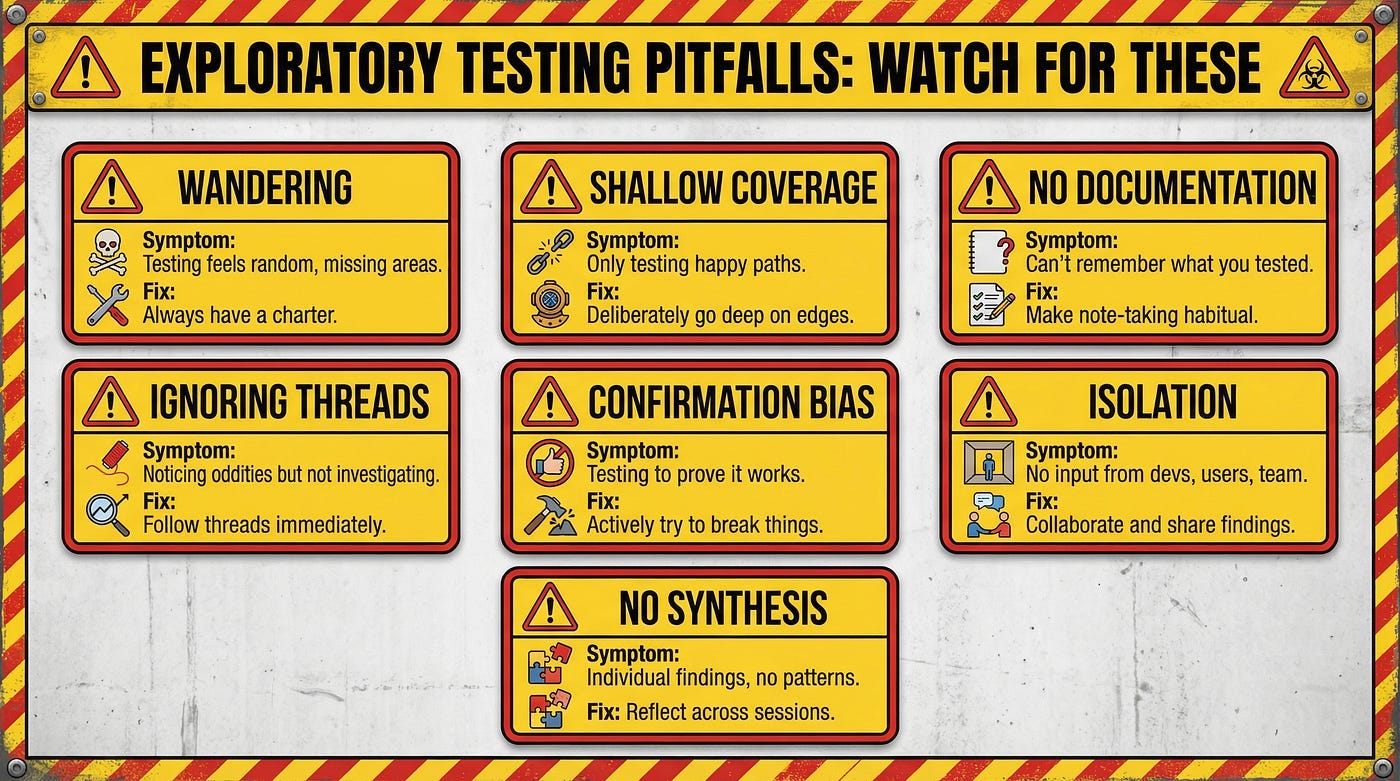

Common Exploratory Testing Pitfalls

Exploratory testing is powerful but not foolproof. Watch for these common mistakes:

Wandering Without Purpose

Exploration without direction degenerates into aimless clicking. You cover ground randomly, missing important areas while over-testing others.

Fix: Always have a charter. Know what you’re investigating and why. Check periodically: “Am I still pursuing my mission?”

Shallow Coverage

Testers sometimes skim across features without going deep. They see that something works at a surface level and move on.

Fix: Deliberately go deep. When something works, ask “But what if…?” Push into edges, errors, and unusual conditions.

Forgetting to Document

In the flow of exploration, documentation gets neglected. Later, you can’t remember what you tested or how you found that bug.

Fix: Make note-taking habitual. Brief notes throughout are better than detailed notes after (when you’ve forgotten half of what happened).

Not Following Threads

You notice something odd but don’t investigate because you’re focused on something else. The thread goes cold. The bug goes unreported.

Fix: Follow threads when they appear. Your current path will still be there. The interesting observation might not be.

Confirmation Bias

You believe the software works and unconsciously test in ways that confirm that belief. You don’t push hard enough to find problems.

Fix: Adopt a skeptical mindset. Your job is to find the truth, not to confirm quality. Actively try to break things.

Working in Isolation

Exploratory testing in a vacuum misses valuable input. You don’t know what developers are worried about, what users complain about, or what other testers have found.

Fix: Collaborate. Ask developers where bugs might hide. Review customer feedback. Share findings with teammates.

No Synthesis

You run sessions, find bugs, write reports — but never step back to synthesize. What patterns are emerging? What does exploration tell you about overall quality?

Fix: Periodically reflect across sessions. Look for patterns. Form hypotheses. Share insights beyond individual bug reports.

Building Exploratory Testing Skills

Exploratory testing looks easy. Mastering it takes years. Here’s how to accelerate your development.

Practice Deliberately

Exploratory testing skills develop through practice — but only deliberate practice that pushes your limits.

After each session, reflect: What did I do well? What did I miss? What would I do differently? This reflection accelerates learning.

Study the Software Deeply

The better you understand what you’re testing, the better your exploration. Learn the domain, the architecture, the history.

Ask developers to explain how features work. Read documentation. Study past bugs. Deep knowledge enables deeper exploration.

Expand Your Heuristic Library

Collect heuristics from books, articles, and other testers. Write them down. Practice applying them.

Over time, you’ll internalize a rich set of mental tools that guide exploration without constraining it.

Learn From Others

Watch experienced exploratory testers work. How do they decide what to investigate? How do they vary their approach? What do they notice that you miss?

Pair exploration is particularly valuable — two minds exploring together, sharing observations and ideas.

Test Everything

Practice exploratory testing everywhere. Test websites you use daily. Test apps on your phone. Test physical products. Test processes.

The more you explore, the more natural exploration becomes.

Review Your Own Work

Record your exploration sessions (screen recording with audio narration). Review them later. What did you miss? Where did you rush? What could you do better?

Self-review is uncomfortable but powerful.

Read Widely

Books like “Exploratory Software Testing” by James Whittaker and “Explore It!” by Elisabeth Hendrickson provide deep insight into exploratory techniques.

Read them. Apply what you learn. Re-read them — you’ll notice different things as your skills develop.

Exploratory Testing and Automation

Exploratory testing and automation aren’t opposites — they’re partners.

Automation Frees Exploration

When routine verification is automated, human testers can focus on exploration. Automation handles the repetitive; exploration handles the creative.

The best testing strategies use automation for regression coverage while reserving human attention for discovery.

Exploration Informs Automation

Exploratory testing discovers what should be automated. You find an important scenario through exploration, then automate it to ensure continuous verification.

Exploration is the R&D; automation is the manufacturing.

Exploration Validates Automation

Are automated tests actually testing the right things? Exploration can answer that question. You might discover that automated tests are passing while real quality issues go undetected.

Periodically explore areas covered by automation. You’ll often find gaps.

Automation Supports Exploration

Automation can set up complex preconditions, generate test data, or monitor for specific conditions while you explore. The tools work together.

Some testers write small automation scripts during exploration — not full test cases, but utilities that support investigation.

Starting Your Exploratory Practice

Ready to start exploring? Here’s how to begin.

Start With One Session

Pick a feature. Set a timer for 60 minutes. Define a simple charter: “Explore [feature] to understand how it works and find any problems.”

Then explore. No scripts. Just investigation guided by curiosity.

Take Notes Throughout

Document what you’re doing, what you notice, what you question. Don’t worry about format — just capture information.

Follow Your Curiosity

When something catches your attention, investigate. Follow threads. Ask “what if?” constantly.

Debrief Yourself

After the session, reflect: What did you learn? What did you find? What would you explore next?

Repeat and Refine

Do more sessions. Try different charters. Experiment with different heuristics. Notice what works and what doesn’t.

Get Feedback

Share your findings with others. Ask for input on your approach. Learn from more experienced exploratory testers.

Your First Exploration Exercise

Let’s make this concrete. Here’s an exercise to practice right now.

Choose an application. Something you use but haven’t tested formally. A website, a mobile app, a desktop application.

Set your charter: “Explore the [specific feature] to learn how it handles unexpected inputs and error conditions.”

Time-box: 45 minutes.

During exploration:

Start with a quick tour of the feature

Identify the inputs and actions available

Apply boundary and invalid input heuristics

Notice how errors are handled (or not handled)

Follow anything surprising

Take continuous notes

After exploration:

List three things you learned about the feature

Describe two bugs or concerns you found

Identify one area that deserves deeper investigation

Write a brief session report

Reflect:

What was easy? What was hard?

What would you do differently next time?

What questions do you still have?

This single exercise will teach you more about exploratory testing than reading three more articles. Do it today.

The Continuous Discovery Mindset

Exploratory testing isn’t just a technique. It’s a mindset — a way of approaching software with curiosity, skepticism, and adaptability.

Scripts ask: “Does the software match our expectations?”

Exploration asks: “What is this software actually doing, and is that good?”

The scripted mindset seeks confirmation. The exploratory mindset seeks discovery.

Both have their place. But in a world where software is increasingly complex, where user behavior is increasingly unpredictable, and where AI is changing what’s possible — the ability to learn and test simultaneously becomes ever more valuable.

The best testers don’t just execute. They explore.

In our next article, we’ll explore Session-Based Test Management — the framework that brings accountability and structure to exploratory testing. We’ll examine how charters, timeboxes, and debriefs transform ad-hoc exploration into a measurable, manageable practice without sacrificing the freedom that makes it powerful.

Remember: Exploration isn’t the absence of structure. It’s the presence of intelligence applied in real-time to the problem of software quality.