Context-Dependent Testing

Why one size never fits all

Welcome back to NextGen QA! Let me start with a question that might seem strange: Should you test a video game the same way you test medical device software?

Of course not. That seems obvious, right? But here’s what’s interesting — I constantly see testers trying to apply the exact same processes, techniques, and standards across wildly different contexts. I see teams force-fitting methodologies that worked brilliantly on one project onto another project where they make zero sense.

Today we’re exploring why context matters more than methodology, and how to adapt your testing approach to fit the unique circumstances of each project.

A Tale of Two Projects

Let me tell you about two hypothetical projects that illustrate context differences perfectly — they’re composite examples drawn from real experiences across the industry.

Project One: Healthcare Records System

Imagine a healthcare records system for a hospital network, replacing a twenty-year-old legacy system with modern software that would manage patient records, medication orders, lab results, and clinical notes for thirty hospitals.

The stakes? Patient safety. A bug could lead to wrong medication, missed allergies, or incorrect diagnoses. The regulatory environment was intense — HIPAA compliance, FDA requirements, and state medical board oversight. The users were doctors and nurses working twelve-hour shifts who had zero patience for software getting in their way during emergencies.

Our testing approach reflected these realities. Every single requirement was traced to test cases. We documented everything in exhaustive detail because auditors would review it. We conducted formal validation sessions with clinicians. We spent weeks on security testing because patient data breaches carry massive fines and destroy trust. We tested error scenarios relentlessly because systems fail at the worst possible moments. We couldn’t deploy updates frequently because hospitals don’t want their critical systems changing constantly.

The testing cycle lasted four months. We found 1,247 defects. We fixed every single one classified as medium severity or higher. We shipped with zero known high-severity bugs. The launch was boring — exactly what we wanted. Systems stayed up. Data stayed secure. Clinicians adapted. Lives were saved without incident.

Project Two: Social Media Photo Filter App

The second hypothetical project is a mobile app that applied fun filters to photos — think puppy ears, rainbow backgrounds, vintage effects. Users were teenagers and young adults looking for entertainment. The app was free with ad-supported revenue. Competition was fierce with new apps launching daily.

The stakes? User engagement and retention. A bug might annoy users or make them uninstall, but nobody’s health or finances were at risk. There were no regulatory requirements beyond basic privacy laws. The users were tech-savvy consumers who expected new features constantly and forgave minor glitches.

Our testing approach was completely different. We focused on the user experience above all else. Does this filter look cool? Is the app fun to use? Can people figure it out without instructions? We tested on dozens of different phones because users had everything from flagship devices to budget models. We did a lot of exploratory testing because users would try things we’d never imagine. We tested performance because a slow app gets deleted immediately.

But we didn’t document everything formally. We didn’t do security penetration testing — just standard best practices. We didn’t trace every requirement to test cases because requirements changed daily based on user feedback. We deployed updates every week or two because users expected fresh content.

The testing cycle lasted three weeks. We found 167 defects. We fixed the critical ones and most high-severity ones. We shipped knowing some minor bugs existed — a filter that occasionally glitched on one specific phone model, a share button that was hard to tap on small screens. We’d fix them in the next release based on user feedback.

The launch was exciting and slightly chaotic. Some users found bugs we missed. We patched them within days. Usage grew. The app succeeded.

The Lesson

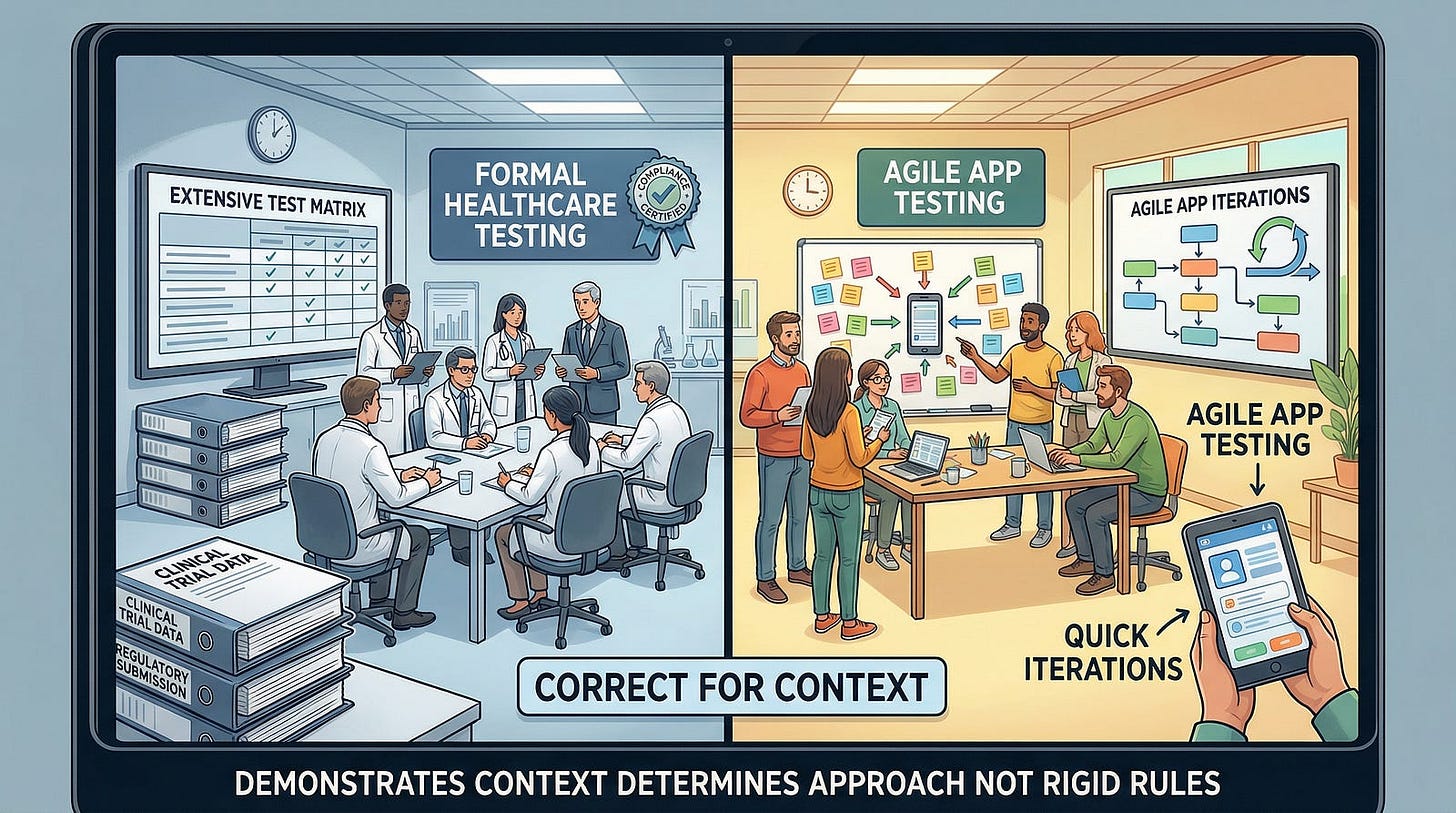

Different contexts. Different testing approaches — and both would be correct for their situations.

If you tested the healthcare system like the photo app, patients would be endangered by inadequate testing. If you tested the photo app like the healthcare system, you’d spend months over-testing a simple app and miss the market window entirely.

Context determines everything.

What Is Context in Software Testing?

Context is the collection of circumstances, constraints, and characteristics that make your project unique. It’s the ecosystem your software lives in, the expectations it must meet, and the consequences if it fails.

Context includes factors you can see immediately — like industry, user base, and technology stack. But it also includes subtle factors like organizational culture, team experience, political pressures, and historical baggage from previous projects.

Experienced testers develop a sense for reading context quickly. They walk into a new project and within days understand what matters and what doesn’t, what needs rigorous testing and what needs light validation, where the real risks hide and where people worry unnecessarily.

Let’s break down the major contextual factors that should shape your testing approach.

Industry and Regulatory Environment

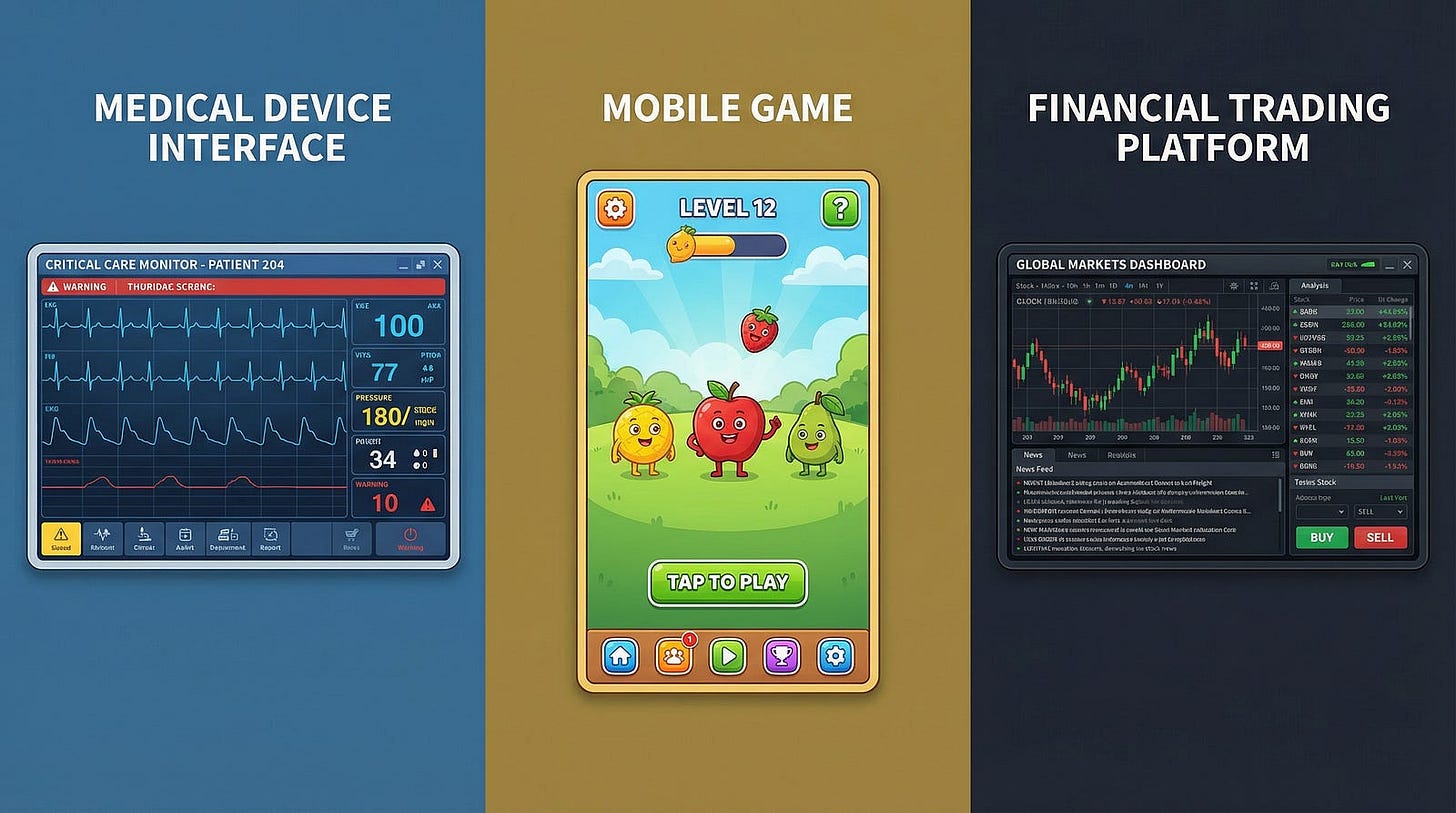

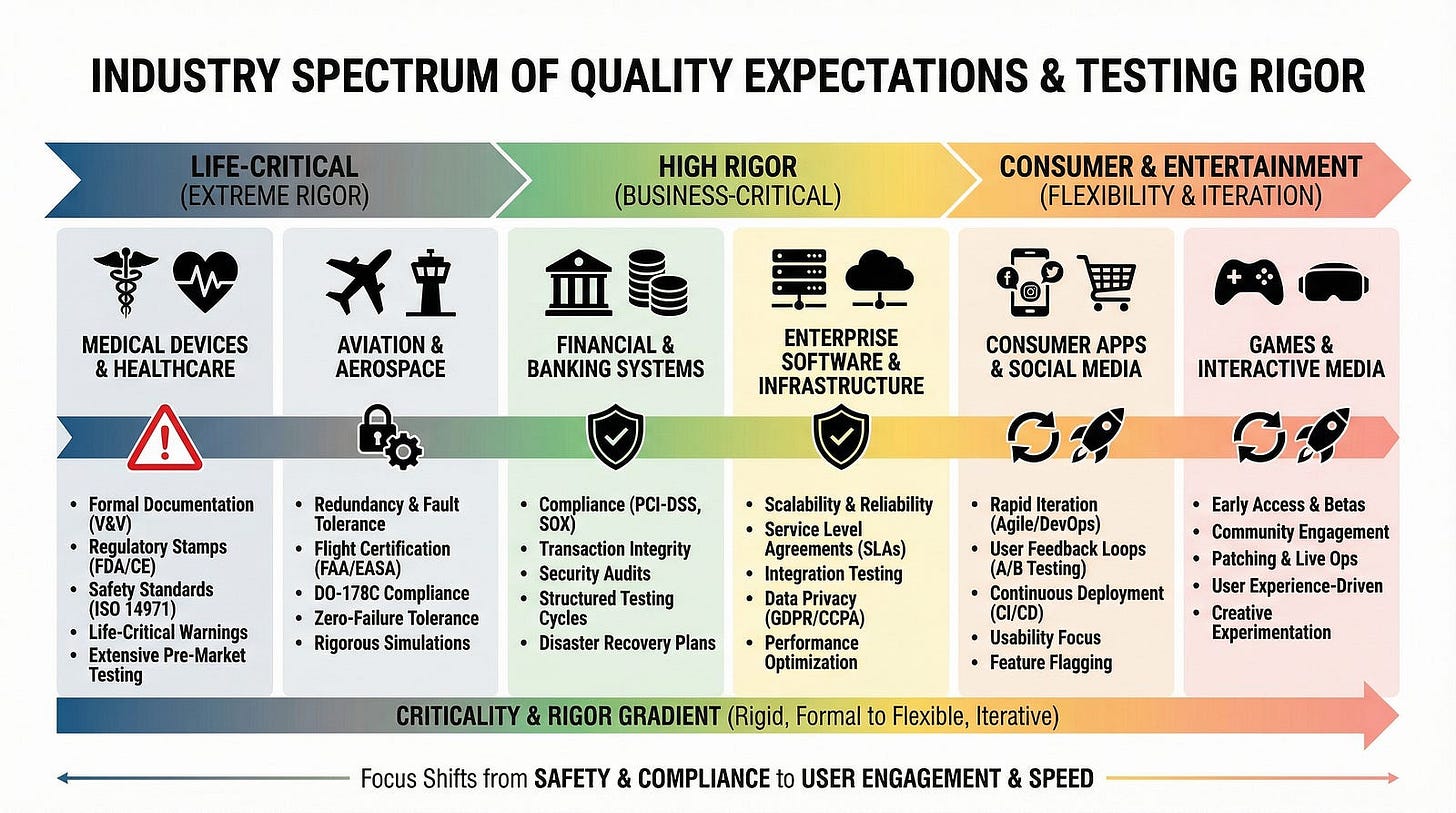

Perhaps the most obvious contextual factor is industry. Different industries have radically different quality expectations and regulatory requirements.

Aviation software goes through certification processes that can take years. Every line of code might be reviewed. Testing documentation fills warehouses. The FAA must approve changes. A bug could crash an airplane and kill hundreds of people. The cost of a single critical defect measured in lives lost and potentially billions in lawsuits justifies extreme testing rigor.

Medical device software faces similar scrutiny from the FDA and international health authorities. Clinical trials may be required. Validation must prove the device works correctly for its intended use. Manufacturing processes must be validated. Post-market surveillance tracks problems in the field. Testing isn’t just thorough — it’s methodical to the point of obsession.

Financial trading systems handle billions of dollars flowing through markets. Bugs can cause financial crises — remember the Knight Capital trading glitch that lost $440 million in forty-five minutes? These systems need exhaustive testing of calculations, extensive security testing, and rigorous disaster recovery testing. But they don’t need the same documentation as medical devices because regulators care more about having proper controls than about seeing every test case.

Social media platforms have different pressures. They need to scale to billions of users. Performance and reliability matter enormously. Security matters because user data is valuable. But perfection isn’t expected — users tolerate occasional glitches. The focus is on testing scalability, monitoring production closely, and fixing issues rapidly rather than preventing every possible defect before launch.

Video games prioritize fun and performance. Yes, games need to work, but users care more about gameplay experience than perfect correctness. A physics glitch that’s amusing might even enhance the experience. Extensive exploratory testing by playtesters matters more than formal test documentation. Patches after launch are expected and accepted.

Understanding your industry context tells you what kind of testing rigor is appropriate, what regulators expect, what documentation is needed, and what failure costs look like.

Risk Tolerance and Failure Impact

Context shapes how much risk is acceptable. This connects directly to our earlier articles on risk-based testing, but context determines what “acceptable risk” means.

In some contexts, shipping with known minor bugs is perfectly reasonable. You’ve identified them, assessed them as low impact, and consciously decided that fixing them before launch isn’t worth delaying the release. Users might never encounter them. If they do, the impact is minimal. You’ll fix them in the next release.

In other contexts, shipping with any known bugs is unacceptable. The potential consequences are too severe. The regulatory environment demands it. The users won’t tolerate it. The reputation damage would be catastrophic.

E-commerce platforms during Black Friday have extremely low risk tolerance. Downtime or bugs during peak shopping season cost millions per hour in lost revenue. Testing before this period needs to be exhaustive, with load testing that simulates peak traffic, careful staged rollouts, and extensive monitoring. The rest of the year? Higher risk tolerance because the stakes are lower.

Internal business tools might have high risk tolerance for minor issues. If your HR system has a cosmetic bug in a rarely-used report, maybe that’s fine for months. Users can work around it. The business impact is negligible. Testing resources are better spent elsewhere.

Consumer-facing applications balance risk against speed. Ship too slowly with excessive testing, and competitors capture your market. Ship too quickly with inadequate testing, and poor quality damages your brand. Finding the right balance depends on your specific context — your competition, your users’ quality expectations, your ability to patch quickly, your reputation resilience.

Startup MVPs (minimum viable products) intentionally accept high risk. The goal is learning whether users want the product at all. Perfect quality doesn’t matter if you’re building something nobody wants. Test enough to ensure the core value proposition works, then get it in front of users. You’ll iterate based on feedback. Many features might be barely tested because they’re experiments that might be removed next week.

Context determines your risk tolerance. Don’t let abstract “best practices” override the reality of your specific situation.

User Expectations and Tolerance

Who uses your software dramatically affects how you should test it.

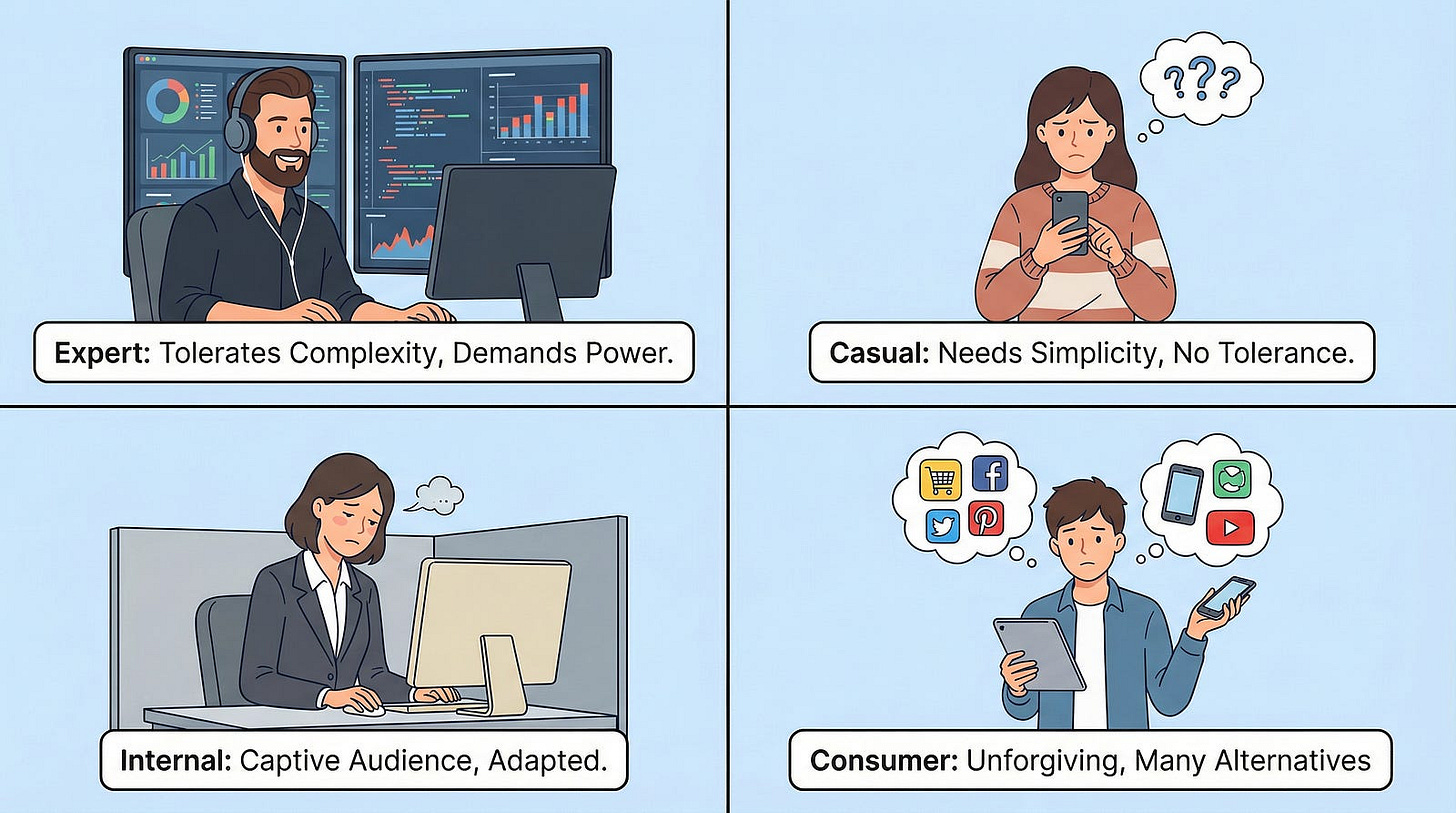

Expert users who rely on your software daily develop deep knowledge. They find workarounds for bugs. They learn quirks and adapt. They prioritize efficiency and power over simplicity. Testing focuses on ensuring advanced features work correctly and performance is excellent because these users push the system hard. A slightly confusing interface is fine — they’ll learn it.

Casual users trying your app for the first time have zero tolerance for confusion. If they can’t figure out the interface immediately, they leave. Testing emphasizes usability above all else. Can a complete novice accomplish the main task without help? Are error messages helpful? Does the interface guide users naturally? Technical correctness matters less than intuitive experience.

Internal corporate users are a captive audience. They have to use your software whether they like it or not. This doesn’t mean quality doesn’t matter, but it changes priorities. Training can compensate for complexity. Documentation can explain workarounds. Bugs can be tolerated if they don’t block critical business functions. The political context matters more than the technical context — who has power to demand changes, whose complaints carry weight, which departments are most influential.

Consumer users are unforgiving. Thousands of alternatives exist. Bad reviews spread quickly. First impressions matter enormously. Testing needs to ensure the critical user journeys are polished to perfection. The onboarding experience gets tested exhaustively. The most common features get intensive testing. Rarely-used edge cases might ship with bugs if finding users would spend months discovering them.

Technical users (developers, sysadmins, power users) have different expectations than mainstream users. They expect configurability and control. They tolerate complexity if it provides power. They want detailed error messages with technical information. They’ll read documentation. Testing focuses on ensuring the technical capabilities work as specified and that advanced configurations don’t break things.

Know your users. Test for their expectations and tolerance levels, not for abstract “quality” divorced from who actually uses the software.

Development Methodology and Team Structure

How your team works shapes how you test.

Waterfall projects with long development cycles and big-bang releases need comprehensive upfront test planning. Test cases are written early. Test environments are carefully controlled. Documentation is extensive. Changes are formally managed. Testing happens in dedicated phases. This isn’t bad — it’s appropriate for contexts where the waterfall approach makes sense, like projects with stable requirements and regulatory needs.

Agile projects with two-week sprints need lightweight, flexible testing. Test planning happens just-in-time. Test cases evolve with the product. Automation enables rapid regression testing. Testers embed with development teams. Testing happens continuously throughout each sprint. Heavy documentation would slow everything down.

Continuous deployment environments shipping code to production multiple times daily need extraordinary test automation and monitoring. Manual testing becomes a bottleneck. Automated tests run on every commit. Production monitoring detects issues immediately. Testing is about fast feedback loops rather than preventing every defect before release.

Distributed teams across time zones create different testing challenges than co-located teams. Asynchronous communication becomes critical. Documentation needs to be clearer because you can’t just walk over and ask questions. Test environments must be accessible globally. Handoffs between time zones need smooth coordination.

Team experience matters enormously. Experienced developers make fewer mistakes and write more testable code. Experienced testers find bugs faster and design better test strategies. Junior teams need more guidance, more structure, and possibly more intensive testing to compensate for inexperience. This isn’t criticism — it’s recognizing reality so you can adapt appropriately.

Team size affects everything. A team of two can’t test like a team of twenty. A massive team faces coordination challenges a small team doesn’t. Scale your testing approach to your team’s actual capacity.

Don’t impose a testing approach that conflicts with how your team actually works. Adapt testing to fit team reality.

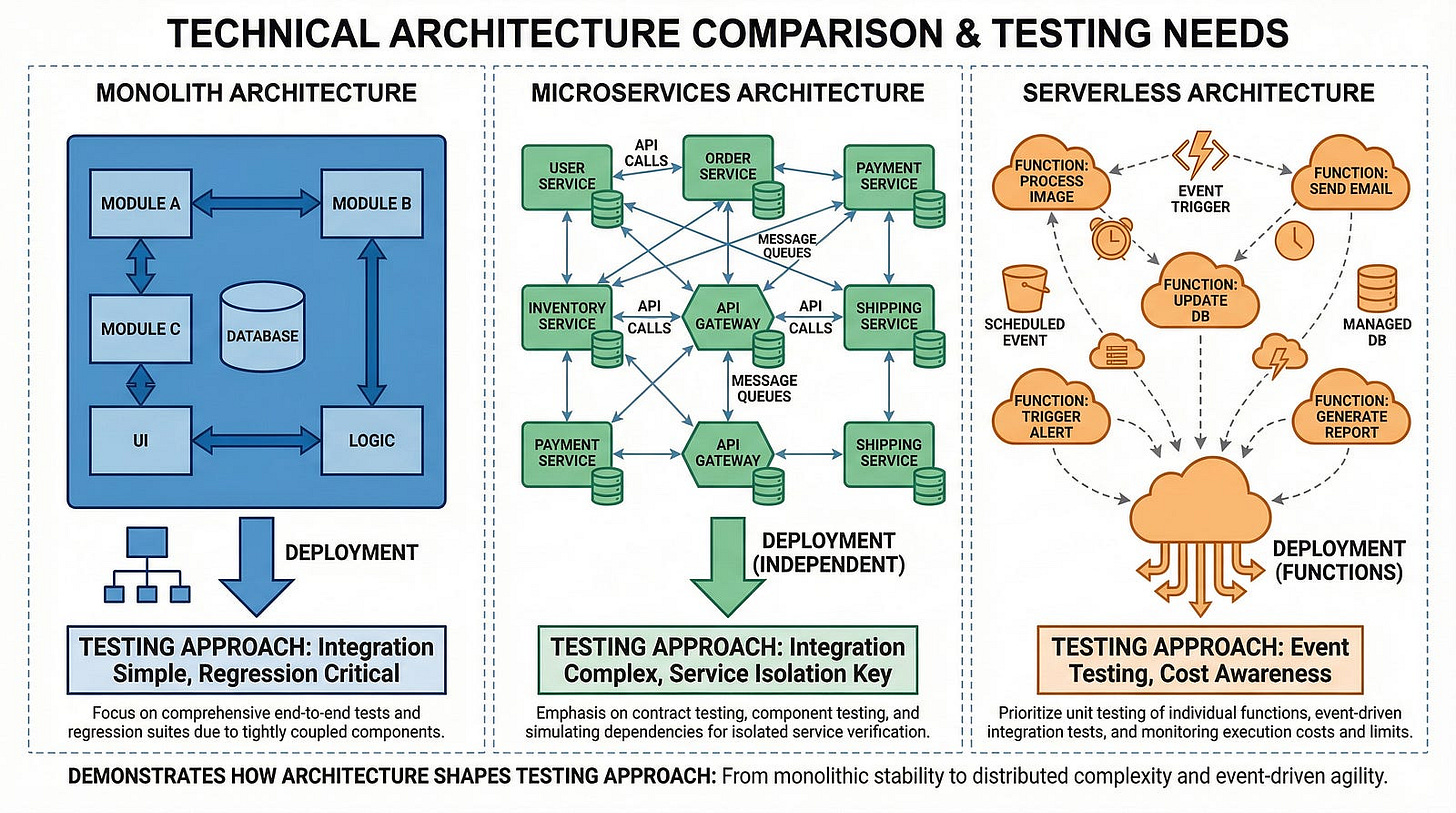

Technical Architecture and Technology Stack

The technology you’re building with and on changes how you test.

Microservices architectures need extensive integration testing because so many independent services must work together. API contracts between services need validation. Service failures need to be tested gracefully. Distributed system challenges like eventual consistency and network partitions require specialized testing. Traditional monolith testing approaches miss these issues entirely.

Monolithic applications have different testing needs. Integration is simpler because everything’s in one codebase. But changes can have ripple effects anywhere. Comprehensive regression testing matters more. Deployment is all-or-nothing.

Cloud-native applications need different testing than traditional server applications. They should handle infrastructure failures gracefully. Auto-scaling needs testing. Cloud service integrations need validation. Cost implications of bugs matter — an infinite loop could cost thousands in cloud compute charges.

Legacy technology stacks might have limited testing tool support. Modern testing frameworks might not work. You adapt by using available tools, even if they’re not ideal, or by doing more manual testing. Complaining that modern tools don’t support your ancient platform doesn’t change reality.

Cutting-edge technology might lack mature testing tools. Early adopters pay a price in tooling gaps. You compensate with more manual testing, building custom tools, or accepting gaps in coverage.

Mobile applications need testing on diverse devices with different screen sizes, OS versions, and hardware capabilities. Network conditions vary wildly. Battery and performance matter. App store approval processes add unique constraints.

Web applications need cross-browser testing. Accessibility testing becomes critical. SEO might matter. Various screen sizes from mobile to desktop need validation.

Real-time systems need timing and latency testing that batch systems don’t. Embedded systems have resource constraints that cloud applications never face. Distributed databases have consistency challenges that single-database systems don’t encounter.

Match your testing approach to your technical architecture. Don’t use a web testing strategy for a mobile app or a monolith testing approach for microservices.

Project Phase and Maturity

Where you are in the project lifecycle changes what testing makes sense.

Early prototypes need light testing focused on validating the core concept. Does the fundamental idea work? Is the basic user flow sensible? Detailed test cases would be wasted on code that might be thrown away next week. Exploratory testing and rapid feedback loops matter more than coverage.

MVPs (minimum viable products) need enough testing to ensure core functionality works but shouldn’t be over-tested. The goal is getting something in front of users quickly to learn. Test the happy path thoroughly. Test critical error scenarios. Skip edge cases that might not even exist in the final product.

Mature products with large user bases need extensive regression testing because breaking existing functionality affects many people. New features need thorough testing, but maintaining existing quality is equally important. The test suite becomes massive over time. Automation becomes essential because manually retesting everything for every release is impossible.

Maintenance mode products receiving only bug fixes and security updates need less active testing than products under active development. Regression testing remains important, but new feature testing drops to near zero.

Products being replaced might need minimal testing. If the plan is to migrate users away from this system in six months, investing heavily in improving its quality makes little sense. Fix critical issues. Otherwise, focus effort on the replacement system.

Don’t test a mature product like a prototype or vice versa. Context changes across the project lifecycle.

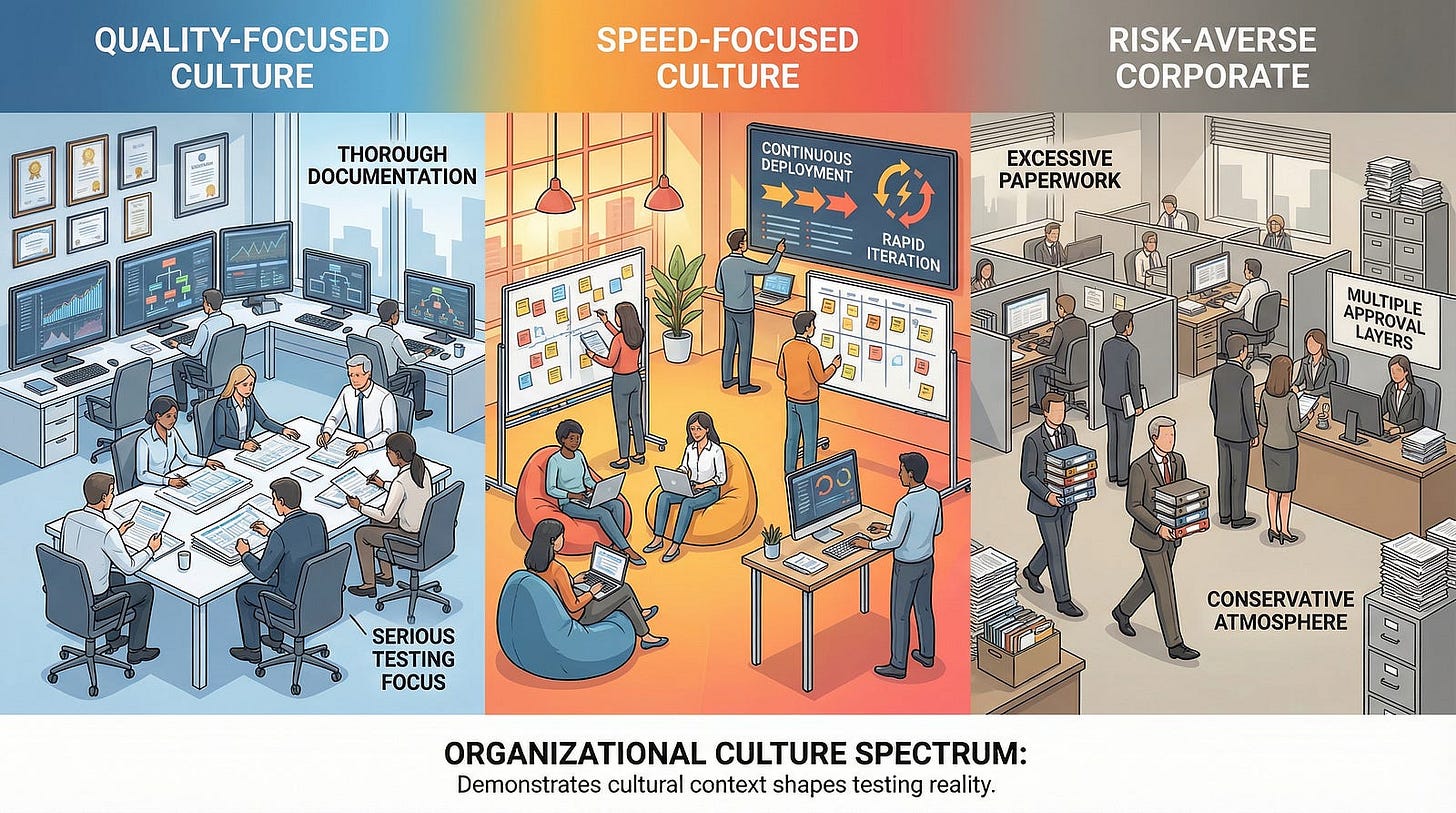

Organizational Culture and Politics

This is the context factor people mention least but that affects testing enormously.

Quality-focused cultures value thorough testing. Testers have respect and authority. Quality gates are enforced. Shipping with known bugs faces serious scrutiny. Testing recommendations carry weight. In this context, testers can push back on premature releases and advocate for fixing issues.

Speed-focused cultures prioritize rapid delivery above all else. “Move fast and break things” is the motto. Testing is seen as a bottleneck to eliminate rather than value to preserve. In this context, testers must be pragmatic. Fighting for exhaustive testing when the organization rewards speed creates conflict and gets you labeled obstructionist. Instead, focus testing on the highest risks and make the business case for quality.

Risk-averse cultures test everything extensively because they fear mistakes. Sometimes this is justified by context — highly regulated industries, critical infrastructure, sensitive data. Sometimes it’s organizational paranoia creating unnecessary process. Testers in risk-averse cultures must balance thoroughness with efficiency, helping the organization test appropriately without over-testing to satisfy anxiety.

Blame cultures where mistakes lead to punishment create defensive testing. Testers over-document everything to avoid being blamed for missed bugs. Developers hide bugs or push back on valid defect reports. Quality suffers as people focus on self-protection rather than improvement. In this toxic context, testing becomes as much about political protection as technical validation.

Collaborative cultures where teams work together toward shared quality goals enable the best testing. Testers and developers partner to prevent bugs rather than playing gotcha. Bug reports are learning opportunities, not accusations. Testing focuses on actual quality improvement rather than blame avoidance or political games.

Understanding organizational culture helps you navigate political realities. The technically correct testing approach might be politically impossible. Adapt to culture while working gradually to improve it.

Budget and Time Constraints

Let’s be honest about the reality all testers face: you never have enough time or resources to test as thoroughly as you’d like.

Some projects have generous timelines and budgets. Government contracts, critical infrastructure projects, and well-funded enterprise initiatives might allocate months for testing with large teams. In this context, comprehensive testing becomes possible. You can test edge cases, automate thoroughly, document extensively, and explore creatively.

Most projects face significant time and budget pressure. Your testing approach must fit within actual constraints, not ideal constraints. A team of two testers supporting a team of fifteen developers can’t test with the same depth as a team of ten testers supporting the same developers. Acknowledging this reality isn’t defeatist — it’s the first step toward strategic thinking.

When time is short, risk-based testing becomes essential. When budget is tight, you prioritize high-value testing over comprehensive coverage. When resources are limited, you focus on what matters most and consciously accept gaps in less critical areas.

The testing approach that works with unlimited time and budget is different from the approach needed with real-world constraints. Don’t feel guilty about this — adapt and do the best possible job within the context you actually face.

Bringing It All Together: Reading Context

Experienced testers walk into new projects and quickly assess context by asking strategic questions and observing organizational reality.

They ask about the industry and regulatory environment. What compliance requirements exist? What happens if this software fails? Who are the users and what are their expectations? They investigate the technical architecture. They learn about team structure and methodology. They observe organizational culture and understand political dynamics. They clarify budget and timeline. They study previous projects to understand patterns and preferences.

Within days, they understand what kind of testing this project needs. They don’t apply templates blindly. They don’t insist on their favorite methodology regardless of fit. They adapt.

When someone asks, “What testing approach should we use?” the only honest answer is: “It depends on context.” Then you start asking questions to understand that context.

Common Mistakes in Context-Dependent Testing

Let’s talk about what goes wrong when testers ignore context.

The methodology zealot insists that agile or waterfall or DevOps or whatever their preferred approach is must be used regardless of project context. They try forcing square pegs into round holes. When it doesn’t work, they blame the organization for “not doing it right” rather than acknowledging their approach doesn’t fit the context.

The one-size-fits-all tester uses the exact same process on every project. Medical device software gets tested exactly like the social media app. Internal tools get the same rigor as consumer-facing products. This wastes effort in some contexts while providing inadequate testing in others.

The perfect-or-nothing tester refuses to adapt standards to reality. If they can’t test “properly” (according to their definition), they won’t test effectively at all. They complain about constraints instead of working within them. They become obstacles rather than assets.

The context-ignorant tester never bothers understanding the bigger picture. They test according to textbook examples without considering whether those examples fit their actual situation. They miss risks because they don’t understand the business context or user expectations.

The culture-blind tester fights organizational culture instead of working with or gradually changing it. They create conflict by pushing approaches that have no chance of acceptance given the political reality.

Don’t be these testers. Read context. Adapt appropriately. Work within reality while gradually improving it.

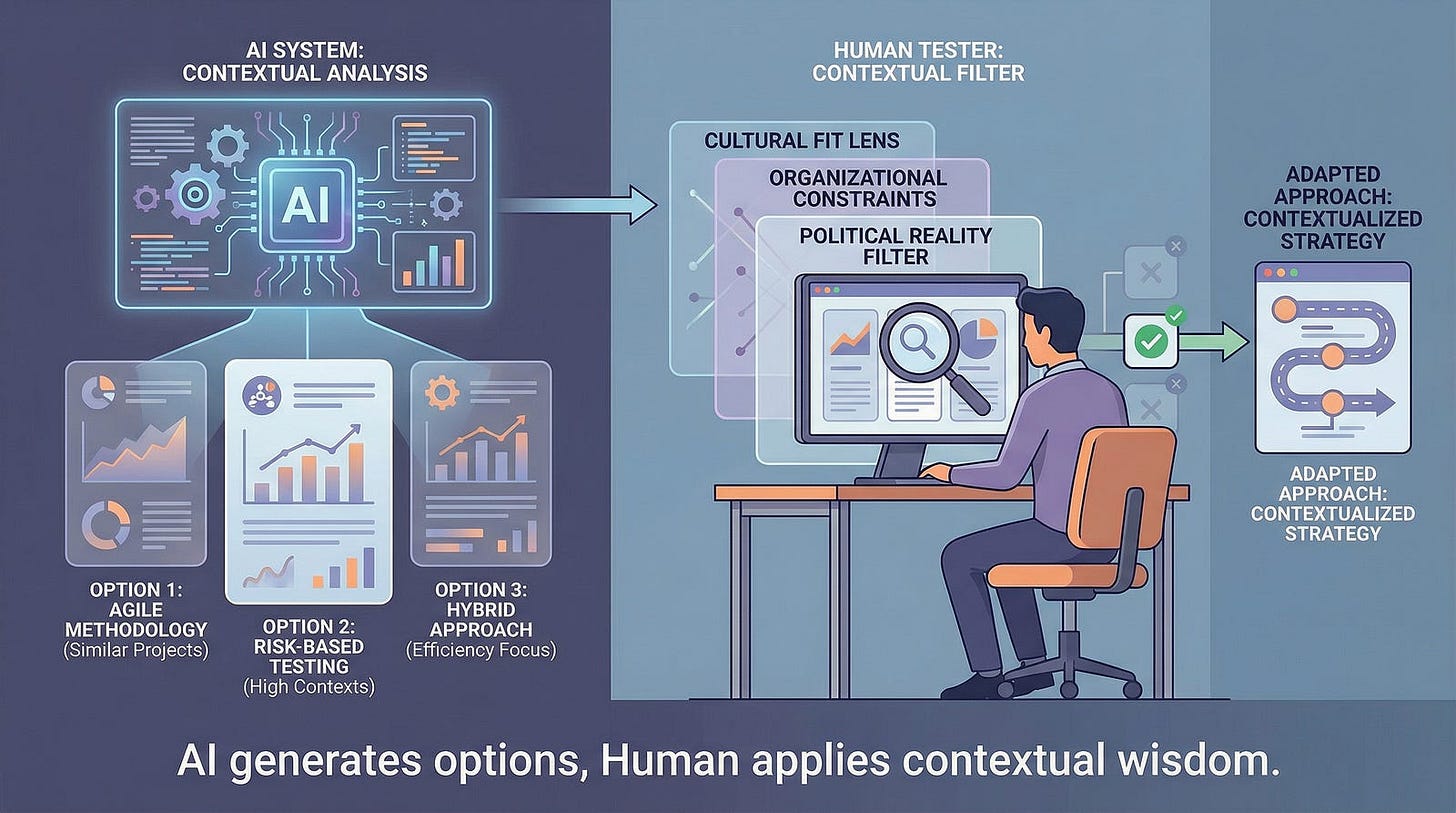

AI and Context-Dependent Testing

Here’s where AI both helps and hurts with context adaptation.

AI excels at pattern matching and can quickly identify similar projects to yours. It can suggest testing approaches that worked in comparable contexts. It can analyze your project characteristics and recommend relevant techniques. This accelerates the context assessment process.

However, AI struggles with nuance and organizational politics. It can’t understand that your company’s culture means certain approaches won’t work despite being technically correct. It can’t feel out the political dynamics or read subtle cues about what’s acceptable. It doesn’t know your team’s actual capabilities versus their stated capabilities. It can’t assess risk tolerance based on unspoken organizational norms.

Use AI to quickly identify potentially relevant approaches and gather information about similar contexts. But apply your human judgment to assess what will actually work in your specific situation. AI provides options. You provide wisdom about which options fit your context.

The “trust but verify” principle applies to AI’s context recommendations. AI might suggest an approach that worked brilliantly elsewhere but would fail miserably in your organizational culture. Your job is recognizing the difference.

Action Steps

Analyze your current project’s context. Write down answers to these questions: What industry are you in? What are the regulatory requirements? Who are your users and what do they expect? What’s your risk tolerance? What’s your team structure and methodology? What’s your technical architecture? What’s your organizational culture like? What are your actual time and budget constraints? How does this context shape what testing approach makes sense?

Compare two different projects. Think of two software projects you know about — either ones you’ve worked on or ones you’ve heard about. How do their contexts differ? How should testing differ between them? What would happen if you used the same testing approach for both?

Read organizational culture. Observe your workplace this week with fresh eyes. Is quality valued or seen as a bottleneck? Do testers have respect or are they marginalized? Is shipping fast more important than shipping right? How do these cultural factors affect what testing approaches will succeed?

Question assumptions. When someone says “We should do X” (implement certain methodology, use specific tools, follow particular process), ask: “Does that fit our context? What context would that approach be ideal for? Is that our context?” Practice evaluating suggestions against reality.

Tell a context story. Share an example with your team of how context shaped a testing decision on a past project. Help others develop context awareness by making these considerations explicit.

Moving Forward

Context-dependent testing is perhaps the most important principle for maturing as a tester. Beginners follow rules and templates. Experts read context and adapt.

There is no universal “best practice” in testing divorced from context. The best practice is understanding your specific situation and applying appropriate techniques that fit. Sometimes that means extensive documentation and formal processes. Sometimes that means lightweight agile approaches. Sometimes that means something in between or something entirely different.

The testing approach that’s perfect for one context might be disastrous for another. The methodology that worked brilliantly on your last project might fail completely on this one if the context is different.

Your value as a tester comes not from knowing the “right” way to test but from assessing context and determining what’s right for each unique situation. That judgment, that wisdom, that ability to read the room and adapt — that’s what separates beginners from professionals.

In our next article, we’ll explore The Pesticide Paradox — why running the same tests repeatedly becomes less effective over time. This connects to context because the “context” of your test suite itself changes as software evolves. Tests that found bugs initially stop finding new bugs. Understanding why this happens and how to combat it will help you keep your testing fresh and effective regardless of your project context.

Don’t force-fit methodologies. Read context, adapt appropriately, and test what matters.