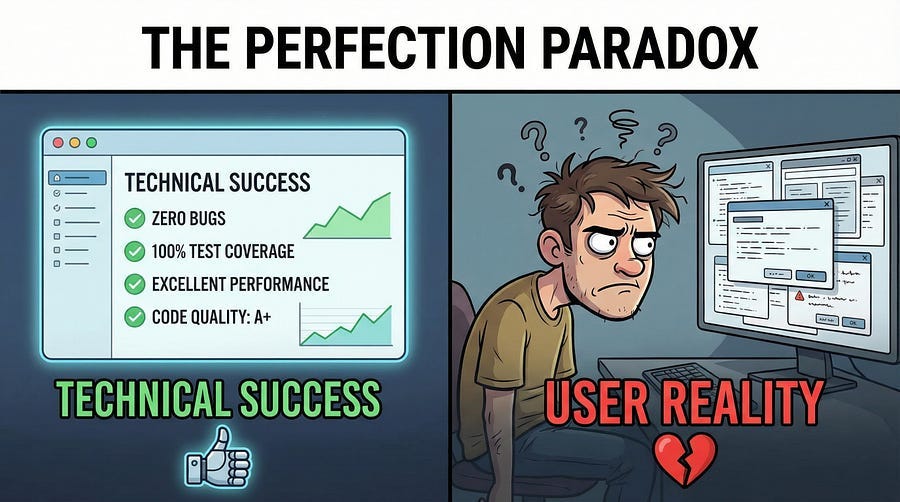

Absence of Errors Fallacy

When bug-free doesn't mean fit for purpose

I need to tell you about the most technically perfect failure I ever witnessed.

A company spent eighteen months building a document management system. They tested meticulously. Every requirement was traced to test cases. Every test case was executed. Every bug was fixed. The test reports were impeccable — hundreds of test cases, zero failures. The code review process caught issues before testing even began. The security audit found no vulnerabilities. The performance benchmarks exceeded targets.

Launch day arrived. The system worked flawlessly. No crashes. No data corruption. No security breaches. Every feature functioned exactly as specified.

And users hated it.

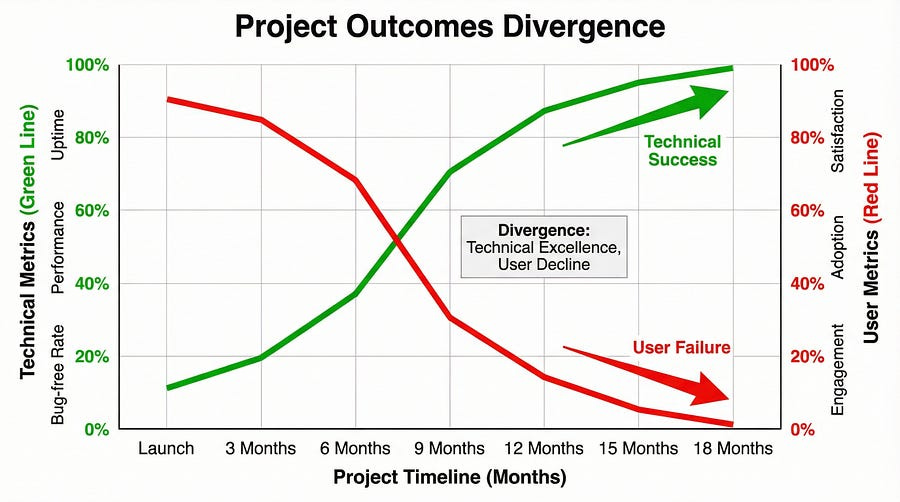

Within three months, adoption rates were so low that executives were considering scrapping the entire project. Not because it didn’t work — it worked perfectly. But because working correctly isn’t the same as working well. Because technical perfection isn’t the same as user satisfaction. Because absence of errors doesn’t guarantee fitness for purpose.

Today we’re exploring why bug-free software can still be a complete failure, and what that means for how we think about testing.

What the Fallacy Actually Means

The Absence of Errors Fallacy is principle seven of our foundational testing principles, and it’s the one most likely to be misunderstood. Here’s what it states:

Finding and fixing defects does not help if the system built is unusable and does not fulfill the user’s needs and expectations.

Read that again. It’s not saying defects don’t matter. It’s not saying you shouldn’t fix bugs. It’s saying that defect-free software can completely fail to deliver value if it solves the wrong problem, serves the wrong users, or works in ways that frustrate rather than help.

You can build a perfect calculator that works flawlessly but if users wanted a spreadsheet application, your perfect calculator is worthless. You can create a messaging app with zero bugs but if the interface is so confusing that people can’t figure out how to send messages, your technical achievement is meaningless.

Testing can verify that software meets specifications while completely missing whether the specifications themselves were worth meeting.

The Document Management System Story (Continued)

Let me tell you what went wrong with that document management system I mentioned.

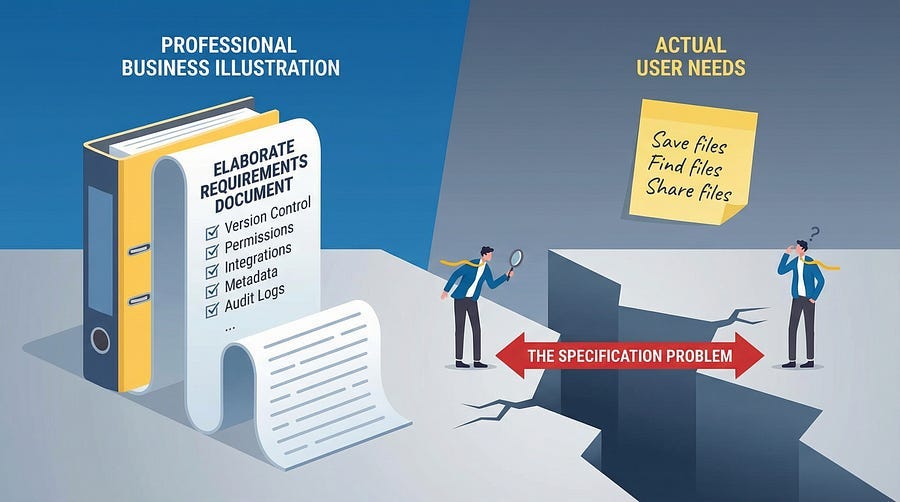

The requirements were written by IT leadership who wanted enterprise-grade features: comprehensive version control, elaborate permission hierarchies, detailed audit logs, integration with seventeen different systems, customizable metadata schemas, and advanced search capabilities that rivaled enterprise search engines.

Testing verified every single feature. Version control worked perfectly — you could track every change to every document with timestamps, user attribution, and rollback capabilities. The permission system was Byzantine but flawless — any combination of user roles, department restrictions, and document classifications worked correctly. Audit logs captured everything with forensic precision. Integrations all functioned. Metadata could be customized infinitely. Search was lightning-fast and precise.

But the actual users — administrative staff, project managers, and department coordinators — just wanted to store files and find them later.

The version control they needed was “save the current version and maybe keep yesterday’s version as backup.” The permission system they wanted was “my team can see these, other teams can’t.” The audit logs they cared about were “who accessed this when” for the occasional security review. They didn’t want to integrate with seventeen systems — they wanted to drag and drop files from their desktop.

The interface reflected the elaborate feature set. Uploading a document required filling out eight metadata fields, selecting from multiple permission templates, categorizing by three different taxonomies, and choosing retention policies. Finding a document required understanding boolean search syntax, metadata field names, and hierarchical folder structures.

Users experienced the system as unnecessarily complex, time-consuming, and frustrating. They wanted a slightly better organized shared drive. They got an enterprise content management system designed for archivists.

The software had zero bugs and zero value.

Testing validated that the specifications were implemented correctly. Testing never validated whether the specifications were correct to begin with.

Beyond Functional Correctness

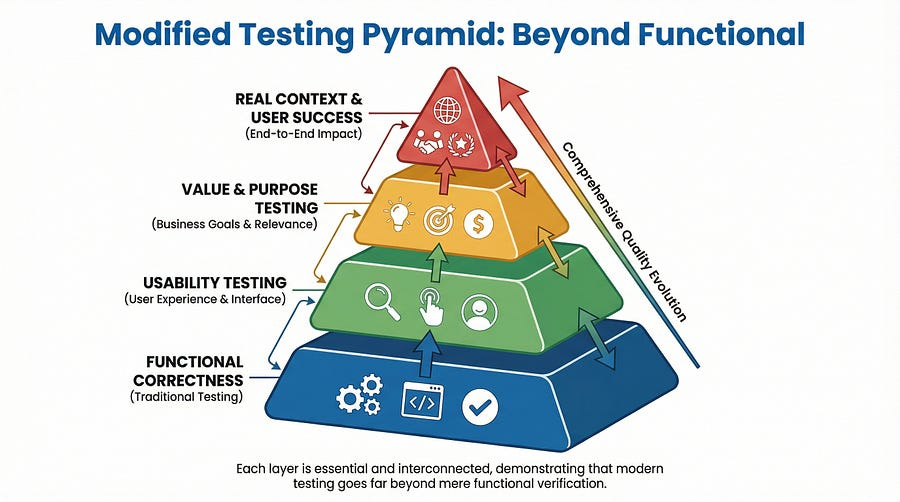

Traditional testing focuses heavily on functional correctness: does the feature work as specified? This is important but insufficient. Software needs to be correct and valuable, functional and usable, bug-free and fit for purpose.

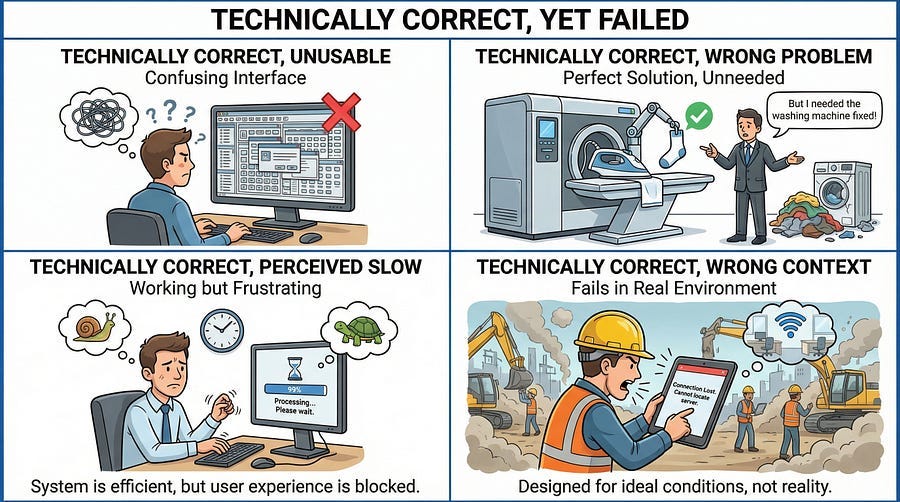

The Usability Dimension

Software can work perfectly while being terrible to use. Imagine a mobile banking app where every transaction requires navigating through seven screens, entering your password three times, and waiting for SMS verification codes twice. Technically, it all works. The security requirements are met. The transactions process correctly. The data is accurate.

But users will switch to a competitor that does the same transactions in three taps because usability matters more than technical correctness to people trying to accomplish goals.

Testing usability means asking different questions than testing functionality. Not “does this button work?” but “can users find this button?” Not “does the form validate inputs correctly?” but “do users understand what inputs to provide?” Not “does the error message display?” but “does the error message help users fix the problem?”

The Performance Perception Gap

Your performance tests might show that pages load in under two seconds — within specifications. But if the user perceives the system as slow because there’s no loading indicator, no progress feedback, and no responsive acknowledgment of actions, the actual speed becomes irrelevant.

Users don’t experience your backend metrics. They experience the feeling of waiting, the uncertainty of whether something is happening, the frustration of clicking buttons with no feedback. Technical performance and perceived performance are different things.

The Value Mismatch

Sometimes software works perfectly but solves the wrong problem. A feature might be implemented flawlessly according to specifications, pass all tests, and still provide zero value because the specifications were based on what someone thought users needed rather than what users actually need.

I’ve seen teams spend months building elaborate reporting dashboards with dozens of customizable charts and filters. Every chart rendered correctly. Every filter worked. Every data calculation was accurate. Testing verified everything.

Then they discovered users were exporting data to Excel and creating their own simple reports because the elaborate dashboard was too complex for their actual needs. They wanted three simple charts. They got fifty complex ones. Technical success. Business failure.

The Context Blindness

Software can work perfectly in the test environment and fail completely in the real context of use. Your mobile app works great on WiFi in your office but becomes unusable on spotty cellular connections. Your web application performs beautifully on the 27-inch monitors your developers use but is incomprehensible on the 13-inch laptops your users have. Your workflow makes perfect sense when you understand the business domain but baffles new employees who don’t.

Testing in artificial conditions can miss context-dependent problems that make software unfit despite technical correctness.

How This Happens: The Specification Trap

The Absence of Errors Fallacy often begins long before testing starts — it begins with specifications.

When requirements are written by people disconnected from actual users, they reflect assumptions rather than needs. When specifications are created in conference rooms rather than informed by user research, they solve theoretical problems rather than real ones. When business analysts translate between users and developers, nuance and context get lost.

Testing then validates these flawed specifications perfectly. Every test case passes. Every requirement is verified. And the resulting software is technically correct but practically useless.

This isn’t the tester’s fault — you can’t test better than the specifications you’re given. But it is testing’s problem because testing that only validates technical correctness without questioning fitness for purpose provides false assurance.

The hard question testers must ask: Are we testing whether the software meets specifications, or whether it meets user needs? Because those aren’t always the same thing.

Real-World Examples of the Fallacy

Let’s look at some famous examples where absence of errors didn’t prevent failure.

The Overly Secure System

A financial institution built a transaction system with elaborate security measures. Multi-factor authentication every five minutes. Session timeouts after sixty seconds of inactivity. Biometric verification for every transaction. Security questions for routine operations. All security features worked flawlessly — zero vulnerabilities found.

Customer service calls increased 300% because customers couldn’t complete transactions. They’d start a wire transfer, get interrupted by a phone call, return to find their session expired, restart, get asked for security questions they’d forgotten, call support. The security was perfect. The user experience was intolerable. Customers moved to competitors with “less secure” (but actually secure enough) systems that didn’t treat every action as a potential threat.

The security testing passed. The usability testing should have screamed warnings.

The Feature-Complete Bloatware

A project management tool implemented every feature any project manager might theoretically need. Gantt charts, Kanban boards, resource allocation, budget tracking, risk matrices, dependency mapping, milestone tracking, stakeholder management, document versioning, calendar integration, and fifty more features. Testing verified all features worked correctly.

Teams tried using it and abandoned it within weeks. Too many features. Too much complexity. Too much configuration required before doing simple task management. They went back to simple tools that did less but did it more easily.

The feature testing passed. The “is this actually helpful?” testing never happened.

The Technically Accurate But Confusing Interface

A medical records system displayed all patient data with perfect accuracy. Every lab result was correct to three decimal places. Every medication was listed with complete pharmaceutical details. Every diagnosis code was precisely accurate according to international standards. Testing verified data accuracy was flawless.

Doctors and nurses complained the interface was unusable during actual patient care. Too much information with not enough hierarchy. Critical alerts buried among routine information. Navigation required too many clicks during time-sensitive situations. The data was perfect. The presentation made it nearly useless in practice.

The accuracy testing passed. The clinical workflow testing revealed disaster.

Healthcare.gov (Revisited)

Remember Healthcare.gov from our earlier article about testing early? The initial launch was a technical disaster — the system couldn’t handle load, integrations failed, data was corrupted. That’s straightforward failure.

But even after those technical issues were fixed, the system struggled because the user experience was terrible. The interface was confusing. The enrollment process was complicated. Error messages were unclear. Many users who successfully navigated the technical obstacles still couldn’t enroll because they didn’t understand what the system wanted from them.

Eventually, both the technical issues and the usability issues were addressed. But those first months showed how technical correctness alone doesn’t guarantee success.

Testing for Fitness, Not Just Correctness

So how do you test whether software is fit for purpose, not just free of defects? You expand your definition of testing.

Include Real Users in Testing

No amount of tester imagination replaces actual users trying to accomplish real tasks. User acceptance testing isn’t just a formal sign-off — it’s your reality check. Bring in real users. Give them real scenarios. Watch what happens without coaching or helping.

When users struggle, that’s a finding as important as any bug. When they can’t figure out how to do something, that’s a defect even if the feature “works.” When they give up in frustration, you’ve found a critical issue.

Don’t just test whether features work. Test whether users can successfully use features to accomplish their goals.

Test the “Why” Not Just the “What”

Traditional test cases verify what the software does: “When user clicks login button with valid credentials, system authenticates user.” That’s important.

But also test why the software exists: “Can a new employee complete their first timesheet without assistance?” That question tests the entire experience, not just individual features.

Frame test cases around user goals, not just system functions. “Can users find the document they need in under two minutes?” is more valuable than “Does the search function return results matching the query?”

Usability Testing as First-Class Testing

Too many organizations treat usability testing as optional or nice-to-have. It’s neither. Usability testing should be as rigorous and systematic as functional testing.

Watch users interact with the interface. Count clicks required to complete tasks. Measure time to complete common workflows. Ask users to think aloud while using the system. Identify pain points, confusion, and frustration. Test with users who match your actual audience — not just developers and testers who understand the system deeply.

Tools like session recordings, heat maps, and analytics show how users actually interact with software in production. Use this data to inform testing and improvement.

Test in Real Contexts

Test on the devices users actually have, not just the latest hardware. Test with the network conditions users actually face, not just your office WiFi. Test with the time pressures users actually experience, not just leisurely exploration. Test with the knowledge users actually possess, not assuming they understand technical concepts.

Context matters enormously. Software that works great in ideal conditions but fails in real-world contexts is not fit for purpose.

Competitive Comparison Testing

Test your software against competitors and alternatives. If users are currently using Solution A and you’re building Solution B, your software needs to be meaningfully better than A — not just defect-free. Being correct isn’t enough if competitors are correct and easier to use.

Ask: why would users switch from what they’re currently using to our solution? Test whether that value proposition is actually delivered.

The “Would I Use This?” Test

Have everyone on the team — developers, testers, product managers, executives — actually use the software for real purposes. Not demo purposes. Not test purposes. Real use.

If you’re building a calendar app, use it as your only calendar for a month. If you’re building an expense reporting system, submit your own expenses through it. If you wouldn’t personally choose to use what you’re building, that’s a major warning sign.

The Tester’s Expanded Role

Recognizing the Absence of Errors Fallacy requires testers to expand their role beyond defect detection.

Question the Requirements

Testers should be empowered to ask: “Why are we building this? Who asked for this feature? What problem does it solve? Have we validated with actual users that this is what they need?”

These questions feel uncomfortable because they challenge decisions already made. But catching a fundamentally flawed requirement before implementation saves far more money than catching bugs during testing.

If a requirement seems disconnected from user needs, speak up. If specifications feel like they were written in isolation from reality, raise concerns. Testing isn’t just executing test cases — it’s being a critical thinking advocate for quality.

Advocate for Users

Testers often have more interaction with the actual product than many stakeholders. You see how features work together (or don’t). You notice inconsistencies. You experience the user journey holistically while developers focus on individual components.

Use that perspective to advocate for users. When you notice something is technically correct but practically frustrating, that’s worth reporting even if it’s not a traditional “bug.”

Frame feedback in terms of user impact: “Users trying to complete Task X will struggle with this interface because…” is more compelling than “This doesn’t seem intuitive.”

Collaborate with UX and Product

Testing, UX research, and product management should be partners, not separate silos. Testers validate that features work. UX validates that features are usable. Product validates that features are valuable. All three perspectives are necessary.

Share findings across disciplines. When testing discovers usability issues, loop in UX. When UX research reveals user needs, inform testing strategy. When product prioritizes features, help assess risk and quality implications.

Measure What Matters

Expand your metrics beyond defect counts and test coverage. Track user satisfaction. Measure task completion rates. Monitor customer support ticket volume and nature. Analyze adoption rates and user retention.

These metrics reveal whether software is fit for purpose in ways that defect metrics alone cannot. A product with ten known minor bugs but ninety-five percent user satisfaction is succeeding. A product with zero known bugs but fifteen percent adoption is failing.

When “Good Enough” Is Good Enough

Here’s a nuanced reality: sometimes shipping with known minor bugs is the right decision if the software delivers real value despite imperfections. And sometimes shipping with zero bugs is the wrong decision if the software solves the wrong problem.

The Absence of Errors Fallacy teaches us that quality isn’t just about defect counts. A product with minor cosmetic bugs that delights users and solves their problems effectively is higher quality than a defect-free product that frustrates users and fails to deliver value.

This doesn’t mean defects don’t matter — they do. It means they’re one factor among many in determining true quality. Fitness for purpose, user satisfaction, value delivery, and usability matter at least as much as defect counts.

Make conscious trade-offs. Fix critical defects. Fix high-impact defects. For minor issues in rarely-used features, consider whether fixing them provides more value than building new capabilities users actually want. Balance technical perfection against practical value.

AI and the Fitness Question

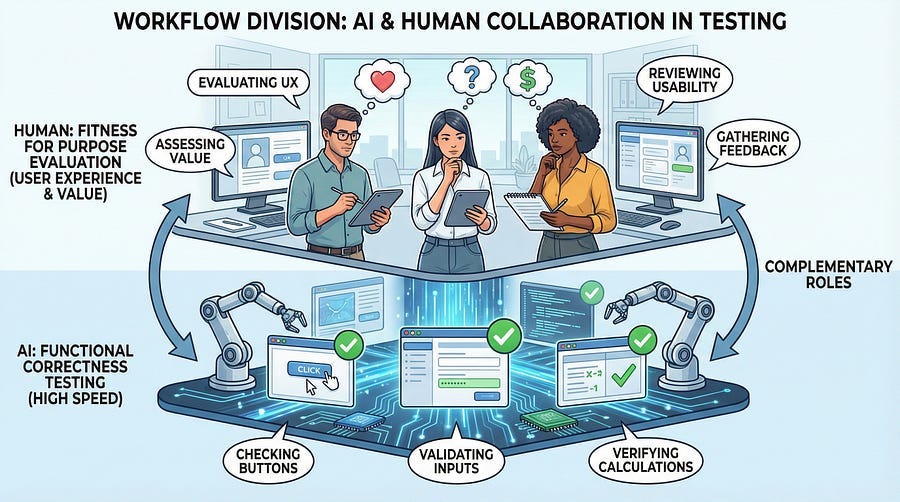

AI tools are getting impressive at functional testing — generating test cases, finding bugs, validating correctness. But AI struggles enormously with the questions at the heart of the Absence of Errors Fallacy.

AI cannot determine whether software is valuable to users. It can’t assess whether an interface is intuitive. It can’t evaluate whether a feature solves a real problem or a theoretical one. It can’t tell you whether users will love or hate what you’ve built. It can’t judge fitness for purpose.

AI can tell you “this button works correctly.” It cannot tell you “this button is in the wrong place and users won’t find it.” AI can verify “this workflow completes successfully.” It cannot tell you “this workflow has too many steps and will frustrate users.”

This is where human testing becomes irreplaceable. The questions of value, purpose, usability, and user satisfaction require human judgment informed by understanding of human needs and experiences.

Use AI to accelerate functional testing. That frees up human testers to focus on the higher-level questions: Is this actually useful? Will users understand it? Does it solve real problems? Is it a joy or a chore to use?

Warning Signs You’re Falling Into the Fallacy

Watch for these indicators that your team might be focusing too heavily on technical correctness while missing fitness for purpose:

All conversations focus on bugs and test coverage, never on user value. If every status meeting discusses defect counts but never discusses whether users will actually want what you’re building, you’re in trouble.

Nobody has talked to actual users in months. If the last time anyone spoke with users was during requirements gathering six months ago, you’re building in isolation from reality.

The team celebrates zero bugs more than user success. If achieving a clean test run generates more excitement than positive user feedback, priorities are misaligned.

Usability concerns are dismissed as “not testing issues.” If feedback about confusing interfaces or frustrating workflows is rejected as out of scope for testing, you’re missing the bigger picture.

Features exist because they’re in the specifications, not because users need them. If the justification for building something is “it’s in the requirements” rather than “users need this,” question whether the requirements are correct.

Test cases validate features work, never question whether features matter. If your test cases all focus on “does this function correctly” and none ask “does this help users accomplish their goals,” expand your testing approach.

Your Challenge This Week

Time to look at your own work through the lens of the Absence of Errors Fallacy.

First, examine your current project. List the last ten features you tested. For each feature, answer honestly: Do you know why this feature exists? Do you know which users need it? Have you seen evidence that users want it? If you can’t answer these questions, you’re testing in the dark about fitness for purpose.

Second, review recent bug reports and test results. What percentage of your testing focuses on functional correctness versus usability, value, and fitness? If it’s ninety-five percent correctness and five percent fitness, your testing is imbalanced.

Third, talk to a real user. Find someone who actually uses your software (or will use it). Watch them try to accomplish a task. Don’t help. Don’t explain. Just observe. Note every moment of confusion, frustration, or unnecessary complexity. Those moments are defects even if no traditional bug occurred.

Fourth, ask the uncomfortable question. If you personally needed to accomplish what this software is supposed to help with, would you choose to use it? If the answer is no or hesitant, dig into why. Those reasons point to fitness problems that testing should address.

Finally, propose one fitness test. Design one test case that validates fitness for purpose, not just functional correctness. Frame it around user success: “Can a new user complete their first purchase in under five minutes without assistance?” Execute it. Report the results even if no technical bugs appear.

The Bigger Picture

The Absence of Errors Fallacy reminds us that quality is holistic. Technical correctness is necessary but insufficient. Defect-free software that users hate is not quality software — it’s well-constructed failure.

Expanding testing beyond functional validation to include usability, value, and fitness for purpose makes testing more challenging. It requires different skills, different perspectives, and different metrics. It means sometimes reporting “this works correctly but users will struggle with it” and having that be taken as seriously as “this crashes when you click submit.”

But this expanded view of testing is what separates great testers from adequate ones. Adequate testers validate that software meets specifications. Great testers validate that specifications — and the resulting software — actually solve real problems for real users in real contexts.

In our next article, we’ll explore Understanding Test Objectives — how to align testing with actual business and user goals rather than just checking boxes on test plans. This builds directly on today’s discussion: if absence of errors isn’t enough, what are we actually testing for? What are the real objectives that should drive testing strategy?

Remember: Bug-free doesn’t mean fit for purpose. Test for both correctness and fitness. Validate specifications, don’t just verify them.

This piece absolutely nails something I've been wrestling with for years. The document management example is painfully familar, reminds me of a CRM project where we added so many 'requested' features that users just went back to spreadsheets. Its funny how the people writing requirements often aren't the ones who have to live with them daily. The spec-reality gap is probably wider than most teams want to admit.